Earlier this year I read Dayswork, a recent book about Herman Melville by husband-and-wife team Jennifer Habel and Chris Bachelder. It’s difficult to classify the book by genre or even describe meaningfully, but it’s primarily about the domestic life of Herman Melville — but not really. It’s catalogued as fiction, but it’s meticulously researched and squarely non-fiction on the whole. It weaves in scenes from Habel and Bachelder’s own marriage as wella s meta scenes about writing the book you have in your hands, though the authors have stated that these parts are not strictly true. But suffice it to say that if you enjoy this blog, then Dayswork is probably for you.

I’m not here to review Dayswork, though, but rather to investigate one particular line concerning the rediscovery of the manuscript for Billy Budd in the early 20th century. The short version, if you’re unfamiliar, is that Melville worked on the novella over the last five years of his life, never quite completing it or even finalizing a title. When he died in 1891, his wife Lizzie stashed it in what’s usually referred to as a “bread box” along with other documents, and there it remained for nearly thirty years. The bread box was finally opened in 1919 when Melville's granddaughter Eleanor Melville Metcalf handed over all of his papers to Raymond Weaver to assist in what would become the first book-length biography of the author. When Weaver discovered the incomplete Billy Budd manuscript, a long lost masterpiece, he helped edit it into as a coherent story and ushered it through publication.

Here’s the except from Dayswork about this chronology, from which you might also get a sense of the book’s unique, almost gonzo style:

After Melville died, Lizzie attempted to collate and annotate the chaotic manuscript, which only made matters more confusing for early editors of Billy Budd, who mistook her handwriting for Melville’s.

She stored the manuscript in a tin bread box where it remained for twenty-eight years—“a literary near-death experience”—until Melville’s granddaughter shared it with Raymond Weaver, Melville’s first biographer.

Remarkably I can find no image of this bread box, which I’ve seen described as “japanned.”

One reviewer on Tripadvisor mentions that it was “great to see” the bread box in the Herman Melville Memorial Room at the Berkshire Athenaeum, but doesn’t describe it.

The improbable story of Billy Budd in the bread box has been told and retold many times over the years, including in a 2017 children’s book about it aptly called "Billy Budd in the Breadbox,” so there’s no need to rehash this tale yet again. What grabbed my attention was the note in Dayswork that the authors were unable to find a single photo of the box anywhere on the internet. Could that really be true? Habel and Bachelder did an impressive amount of research for their book, but this felt impossible or, at the very least, easily remedied.

To put it more bluntly: even though I’d never thought about this box for one second before reading that line, I knew instantly that I couldn’t rest until I found a picture of it. I had to see that box.

The Bread Box

It seemed like a good idea to gather some information about this box, which again is alternately said to be a “bread box” and also “japanned” — a term I just learned and which basically means ‘lacquered.’ Aaron Sachs’ recent biography of Melville also tells us that it was sometimes (incorrectly) called a “cake box,” and that Lizzie would haul it out when fans came to pay their respects — even allowing them to flip through the pages of Billy Budd.

Lizzie was solicitous of his posthumous reputation, encouraging friends and admirers to compose memorial tributes and even republish some of his novels. She seems not to have made any effort to get “Billy Budd” into print, though. Instead, she put the muddled manuscript in what one visitor called “a japanned tin cake-box,” together with Melville’s travel journals and remaining poems. The box passed from Lizzie to her older daughter Bessie, and then to Bessie’s sister Fanny, and then to Fanny’s older daughter Eleanor—who insisted that it was a bread box, not a cake box, and who opened it for Raymond Weaver in 1919, the year Melville would have turned one hundred. Weaver brought out the first edition of “Billy Budd” in 1924, though he used a title that Melville had discarded: “Billy Budd, Foretopman.”

Eleanor had always been enthralled by the box. Early in the twentieth century, Lizzie would occasionally invite Eleanor to join her for long evenings in the parlor, on the rare occasions when an admirer of Herman’s writings came to call. Eleanor, in her early twenties, knew that she was being primed to become the steward of her grandfather’s reputation. While Lizzie guided the conversation, Eleanor would gaze around at Melville’s old books, and at the portrait of him that hung over “the white marble mantelpiece,” and at “the precious box of manuscripts,” placed prominently on “the same table where he used to write.” Sometimes, they would even leaf through the pages of “Billy Budd” and several “fugitive, discarded, or rewritten poems.”

Some of Sachs’ information came directly from Eleanor, the granddaughter, who wrote about the box herself in her 1953 book “Herman Melville: Cycle and Epicycle.” Eleanor also provides the full provenance of where it had been kept through the years:

Among my most cherished girlhood memories were the visits made to my grandmother's apartment…. We would sit in the library, surrounded by the remaining books of Melville's collection, himself looking down on us from his place over the white marble mantelpiece, as alive as the artist Eaton portrayed him, the precious box of manuscripts on the same table where he used to write. While “Billy Budd" and fugitive, discarded, or rewritten poems were inspected, I listened with ignorant enthusiasm to their conversation. […]

In 1908 my aunt's place too was vacant. The Thomas family became custodians of the remaining belongings of Herman Melville. My mother, who as late as 1928 could say, “I don’t know him in the new light," nevertheless had a clear sense of rightness in her guardianship of his literary remains. The famous so-called ‘‘trunk" (in reality a bread box), in which my grandmother had kept unpublished manuscripts, came to my father's house in South Orange, to be stored most of the time in the attic.

As far as where the box is now, you’ll recall from Dayswork the comment on TripAdvisor.com suggesting that it lives at the Herman Melville Memorial Room at the Berkshire Athenaeum. And while I wouldn’t normally vouch for the accuracy of TripAdvisor reviews, in this case it’s true. In fact, the box has been at the Athenaeum since 1953 when its Melville room was inaugurated. On April 20th of that year, the Berkshire Eagle previewed the dedication of the room later that week, describing some of the artifacts donated by his family and early Melville scholars:

Among the most interesting [items] are such personal possessions as Melville’s… battered tin bread box in which his manuscripts were preserved by his wife.

I tried some simple searches for images of the box, and then a few not-so-simple ones, and had to admit that there was no low-hanging fruit after all. But I did come across a more detailed description of the box from writer Peter McLaughlin, who visited the Berkshire Athenaeum for the North Adams Transcript and gave some additional details about the box:

That black tin box, about one foot square, sits in the Melville Room on one of the author's library tables and in an adjacent display cabinet is a little lock and key with a label attached in Mrs. Melville's handwriting: "Padlock to tin box with Herman's Mss."

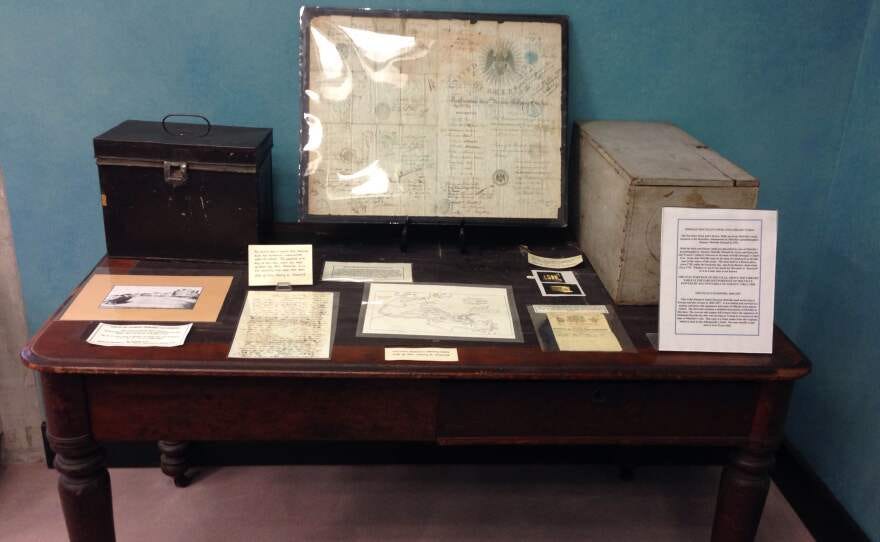

That description sounded a lot like an image I had come in a December 2015 article by Jim Levulis of WAMC Northeast Public Radio. Levulis was writing about the various places in western Massachusetts one can find Melville artifacts, published to coincide with the release of the film adaptation of Nathaniel Philbrick’s In the Heart of the Sea. The article doesn’t mention the bread box or even Billy Budd, but check out the fourth image in the photo gallery at the top, which has the caption: “Melville's desk at the Berkshire Athenaeum.”

Could that black box on the left be what we’re looking for? The text on the museum label is too small to read, but it sure seemed to fit the bill. There’s even a spot for a padlock. Maybe that’s a sample page of the manuscript sitting in front of it?

The simplest way to confirm was to reach out to the Berkshire Athenaeum to see if they could tell me whether it was indeed the box, and better yet, if they had any other photos they’d be willing to share and let me use here. Mere minutes later I heard back from David Laczak, a technician at the library’s Local History and Genealogy Dept. “That is indeed the bread box in photo 4 (the dark one on the left)!”

After signing a few release forms, he also sent over the most exciting photos of a plain black box you’ll likely ever see:

The card in front of the box reads:

Tin bread box in which Mrs. Melville kept her husband’s manuscripts after his death. The padlock and key to this box, with the label written by Mrs. Melville, is in the display case near the door.

Gift of Mrs. Henry K. Metcalf

“Mrs. Henry K. Metcalf” is, of course, Eleanor Metcalf, Melville’s granddaughter whose book I quote above.

So while it turns out there actually had been a picture of the bread box on the internet all along, thanks to the fine folks at the Berkshire Athenaeum, Melville nuts like from around the world can now marvel at it without having to leave home.

It’s a good box!

Yay!