Whenever I read books or articles which discuss Melville’s influence on other writers, I often find it’s the same recitation of names and quotes we’ve all seen a hundred times. Stop me if you’ve heard this before.

When William Faulkner was asked what he thought was the single greatest book in American literature, he answered “Probably Moby-Dick,” saying that it was the one book he wish he’d written and read it every year. Toni Morrison called Moby-Dick “a complex, heaving, disorderly, profound text.” Maurice Sendak called Melville “a god” and a “genius.” Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote that the opening paragraph of Moby-Dick is “the greatest paragraph in any work of fiction, at any point, in all of history. And not just human history, but galactic and extra-terrestrial history too.” And so on.

Vladimir Nabokov said late in life that he “still loves Melville,” a statement all the more notable given what little respect he had for most American writers. (He was also asked which scenes from history he wished had been caught on film. His list included the beheading of Louis XVI, the wedding of Edgar Allan Poe to his first cousin, and “Herman Melville at breakfast, feeding a sardine to his cat.” Who could disagree?)

It’s not that Melville doesn’t have countless famous admirers across time and disciplines, but it seems that when it comes to evidence for Moby-Dick being the Great American Novel, there are too many ‘big’ names and too much low-hanging fruit.

So I was caught off-guard when I happened to see the cover of this recent Portuguese edition of Moby-Dick published in Brazil. More specifically, I noticed some of the extra content advertised on the front, including a certain preface:

A prefácio? De Albert Camus?

I had vague recollections of seeing Camus’ name from time to time in the Melville world, often just stray fragments of unattributed quotes. Earlier this year, for instance, I read Dayswork by Chris Bachelder and Jennifer Habel, which mentions in a flyby that Camus called Billy Budd a “flawless story,” though it’s not clear when, where, or why. In Timothy Marr’s essay for the 3rd Norton Critical Edition of Moby-Dick, Camus is included in a long list of authors who Marr says were caught in Melville’s “whale lines,” but without any further detail. And a quick search revealed several more instances where Camus is quoted as calling Melville a “genius.” But in all of these cases the mention has no information on where it came from.

It was that elusiveness which beckoned me — a “spirit-spout” — knowing all the while that somehow it all led to an essay of Camus’ thoughts on Melville used in that Portuguese translation. Luckily, I took a lot of French in college (shoutout to Professor Erickson); but, much more luckily, we live in a world with Google Translate, because first I was about to be staring at a whole lot of French.

Call Him Sisyphus

Before I even got to that essay or what Camus said about Melville, my immediate question was whether Moby-Dick, and specifically the morose first paragraph of Chapter 1, had any influence on The Myth of Sisyphus (1942). I’ve always thought Moby-Dick is underrated as a proto-Existentialist text, loosely framed as it is by Ishmael’s rejection of suicide and choice to abandoning his mundane life to go whaling.

Consider the opening paragraphs of Sisyphus:

There is but one truly serious philosophical problem and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy. All the rest — whether or not the world has three dimensions, whether the mind has nine or twelve categories — comes afterwards. These are games; one must first answer. And if it is true, as Nietzsche claims, that a philosopher, to deserve our respect, must preach by example, you can appreciate the importance of that reply, for it will precede the definitive act. These are facts the heart can feel; yet they call for careful study before they become clear to the intellect. […]

Whether the earth or the sun revolves around the other is a matter of profound indifference…. I see many people die because they judge that life is not worth living. I see others paradoxically getting killed for the ideas of illusions that give them a reason for living (what is called a reason for living is also an excellent reason for dying). I therefore conclude that the meaning of life is the most urgent of questions. How to answer it?

Now compare that to Ishmael’s morose thoughts in the opening paragraphs of Moby-Dick, or even Ahab’s decision to kill the white whale even at the expense of his own life. Ishmael dwells on death throughout the book and philosophizes about how it influences how we should live our lives.

All men live enveloped in whale-lines. All are born with halters round their necks; but it is only when caught in the swift, sudden turn of death, that mortals realize the silent, subtle, ever-present perils of life. And if you be a philosopher, though seated in the whale-boat, you would not at heart feel one whit more of terror, than though seated before your evening fire with a poker, and not a harpoon, by your side.

Robert Milder, writing in his book Exiled Royalties: Melville and the Life We Imagine, similarly found a shared philosophy between the two, highlighting a change in Melville’s thinking just as he was writing (or re-writing) Moby-Dick and his pseudonymous review of Hawthorne’s “Mosses from an Old Manse.”

In the term “blackness” in the “Mosses” essay Melville found a liberating metaphor that allowed him to beg the question of ultimate reality while fronting what he would elsewhere call “the visible truth.” Neither an objective outward force nor a purely subjective inward feeling, blackness arose at the meeting point of mind and world. Like Camus’s Absurd, it was essentially a relationship—in Camus’s words, a relationship “between the human need and the unreasoning silence of the universe”—that came into being as the perceived nature of reality, neutral in itself, impinged on human demands for order and meaning and called forth an almost visceral anger and revulsion. Camus’s hero can defiantly laugh at the Absurd because his stance toward it is one of detached intellectual lucidity, yet even Camus could lapse into the emotive language of blackness with a phrase like “the primitive hostility of the world.” Without falling into cosmic personification, “blackness” built upon a nearly involuntary sense of the antagonism of Creation. It expressed not only how humans saw the gap between need and fact but how they felt about it; it was a philosophical judgment charged with latent anthropocentric protest at life’s betrayal.

The way that Camus defines the Absurd in that quote — as being “born of this confrontation between the human need and the unreasoning silence of the universe” — sounded to me uncannily like a central theme of Moby-Dick. And thinking about Melville writing it in the mid-19th century, it’s no wonder he felt that he had written a “wicked book,” one which openly questioned man’s relationship to god and nature.

As I kept digging into Camus’ own writing and thoughts on Melville, I found that he also talked about their shared fascination with that “antagonism of Creation.” In December 1957, Camus told an audience at Uppsala University that “The highest work will always be, as in the Greek tragedies, in Melville, Tolstoy, or Molière, one which balances reality and the refusal of a man opposed to this reality, each bouncing off the other in an incessant outpouring in the same joyful and agonized life.” Or, as Ishmael put it: “Ah, the world! Oh, the world!”

Although Camus openly admitted Melville’s influence on his work, the open question specifically about Sisyphus hit brick wall, or perhaps a giant boulder. The problem is that no one knows for sure when, exactly, Camus first read Moby-Dick. Most likely, scholars agree, it wasn’t until a French translation was published in the spring of 1941 — too late to be an influence on Sisyphus, which he had completed by February of that year. But as I’ll explore in another post, there’s actually plenty of reason to believe that’s not the whole story.

Solitary Minds

Whether it was his first time reading it or his 10th, it’s all but certain that Camus read the 1941 translation soon after it was published. He made “careful notes” in the margins, according to biographer Oliver Todd, and thought deeply about how he might be able to recreate in his own writing the clarity and insight he saw in it: “Feelings and images multiply philosophy tenfold.” (The book also inspired for a private nickname for his domineering mother-in-law: “Moby Dick.”)

When I looked deeper into Melville’s influence on Camus, I was actually surprised at how extensive it really was. For example, in March 1946 Camus spent four months traveling in the US and Canada, to coincide with the first English translation of The Stranger. Camus at this point was still largely unknown to American audiences, at the time working as a literary editor and plugging away on his next novel, The Plague. But by the end of his press tour, which included a photo shoot for Vogue, interviews for radio and print, and lectures at universities like Harvard, Columbia, and Bryn Mawr, he was on his way to being an international celebrity.

His journals from his trip betray mixed emotions about the U.S., though, at turns put off by chatty Americans, charmed by their generosity, and puzzled by the intense consumer culture. He was also keenly aware of the superficiality of the glitz and glamor of New York, so much so that he was relieved to encounter poverty “which gives a European the urge to say: ‘At last, reality.’ The real wreckage.”

Melville’s most documented influence on Camus was during this exact period, “an inspiration for Camus’ turn to allegory in The Plague,” writes Alice Kaplan, and being in New York City must have been a constant reminder of his presence. He spent one evening with writer and political activist Waldo Frank, and the two men discussed Melville’s life as an example of the solitary American genius. He wrote in his journal:

W. Frank. One of the few exceptional men I’ve met here. He despairs a little for today’s America and compares it to that of the XIXth century. “The great minds (Melville) have always been solitary here.”

The following day, he visited an art museum and admired the work of American painter Albert Pinkham Ryder, which reminded him of Melville and “America’s greatness.”

Monday. Ryder and [Pedro] Figari. Two truly great painters. Ryder’s paintings, with their mystic inspiration and almost traditional technique (they’re almost enamels), inevitably call Melville to mind…. Yes, America’s greatness is there.

To be fair, Ryder’s work does at times recall the painting at the Spouter-Inn, especially this one of Jonah and the Whale:

Melville was still on his mind when he sat for an interview with Dorothy Norman of the New York Post. Again his focus was on his favorite American writers and not the glamor of the city:

Camus himself is a modest man. You feel it in everything he says. You feel it in the way he comments on New York. It is not our skyscrapers that have moved him, but our Bowery. He likes our literature of the 19th century—Melville and Henry James—better, so far, that what he has read of the 20th century.

When he returned to Paris and continued working on The Plague (La Peste in French), Melville remained his lodestar. “La Peste may be read in three ways,” he wrote. “It is at the same time a tale about an epidemic, a symbol of Nazi occupation …, and, thirdly, the concrete illustration of a metaphysical problem, that of evil … which is what Melville tried to do with Moby-Dick, with genius added.” He even bristled at the idea that he might also be indebted to fantastical writers like Kafka, stating in an interview with Les Nouvelles littéraires that while he admired Kafka’s abilities as a storyteller, he was more inspired by Melville’s embrace of the Absurd.

I consider Kafka to be a very great storyteller. But it would be wrong to say that he influenced me. If a painter of the Absurd played a role in the idea I have of literary art, it is the author of the admirable Moby Dick, the American Melville... I believe that what pushes me away a little, in Kafka, it's the fantastic. I'm not comfortable with fantasy. The artist's universe must exclude nothing. But Kafka's universe excludes almost the entire world. And then... and then, I couldn't really get attached to a totally desperate literature.

The process of writing and revising The Plague went on for several frustrating years, leaving Camus with a book that had grown so unwieldy that he began to doubt himself. “I am blind in the face of this bizarre book, whose form is slightly monstrous,” he complained in his journal. Once more he looked toward Melville for inspiration, pausing during his final revisions in August 1946 to read Lewis Mumford’s 1929 biography of Melville. He jotted down a telling quote in his notebook signaling his frustration, a line from a letter Melville wrote to Evert Duyckinck in December 1849: “What a mad, inconceivable thing that a writer cannot—in any conceivable circumstance—be frank with his readers.” (Curiously, this slightly misquoted line doesn’t actually appear in Mumford’s biography, suggesting that Camus’ reading perhaps went even beyond this volume.)

Above all, it was Melville boundless ambition and fearlessness even in the face of total failure that inspired him:

The ambitions of a Lucien de Rubempré or a Julien Sorel often disconcert in their naïveté and their modesty. Nietzsche’s, Tolstoy’s, or Melville’s overwhelm me, precisely because of their failure. I feel humility, in my heart of hearts, only in the presence of the poorest lives or the greatest adventures of the mind.

The Chapel of Melville

Melville’s most overt period of influence on Camus’ writing might have ended after The Plague was finally published in 1947, but their shared despondency as writers seems to never have left him. In late October 1949, at the age of 36, he suffered a relapse of tuberculosis which he’d contracted as a teenager and fell into a depression. During his convalescence he read a newly-released biography of Melville in French by Pierre Frédérix, finding comfort in a particularly morose line which he again wrote in his notebook: “Melville at the age of thirty-five: I have give my consent to annihilation.” Another line that caught his eye: a comment that Nathaniel Hawthorne made about Melville: “He can neither believe nor be comforted in his unbelief.”

Although Melville’s direct influence might not have been so keenly felt in the last decade of his work (his next novel, The Fall, was the last before his death in an car accident in 1960), Camus continued to cite him as a major influence in his thinking and as one of the best kinds of novelists:

We no longer tell “stories”, we create our own universe. The great novelists are philosophical novelists, that is to say the opposite of thesis writers. Thus Balzac, Sade, Melville, Stendhal, Dostoievsky, Proust, Malraux, Kafka, to name just a few.

In 1951, he ranked Melville beside Aeschylus, Shakespeare, Hugo, Baudelaire, Nietzsche, and Rimbaud as the greatest of all time. These writers “sang of the whole man,” he said. “I will continue to attend their chapel.”

O Prefácio

So, back to that preface from the Portuguese edition. The publisher, Editora 34, doesn’t give much detail about the essay on its website, saying only that ‘this new edition features a preface by Albert Camus [is] unpublished in our country’ and translated to Portuguese. But I was able to confirm with someone who owns a copy that the essay is one which originally appeared in the third volume of Les Ecrivains Célèbres, an 1952 anthology of essays by contemporary writers about major literary figures from around the world, paired with a photograph or portrait.

It’s not clear whether Camus was asked to contribute one for Melville or he simply volunteered, but it certainly gives the sense of someone who had been waiting to pour out their thoughts and praise on one of their heroes. “In judging Melville's genius,” he begins, “if nothing else, it must be recognized that his works trace a spiritual experience of unequaled intensity.” Not exactly playing it cool.

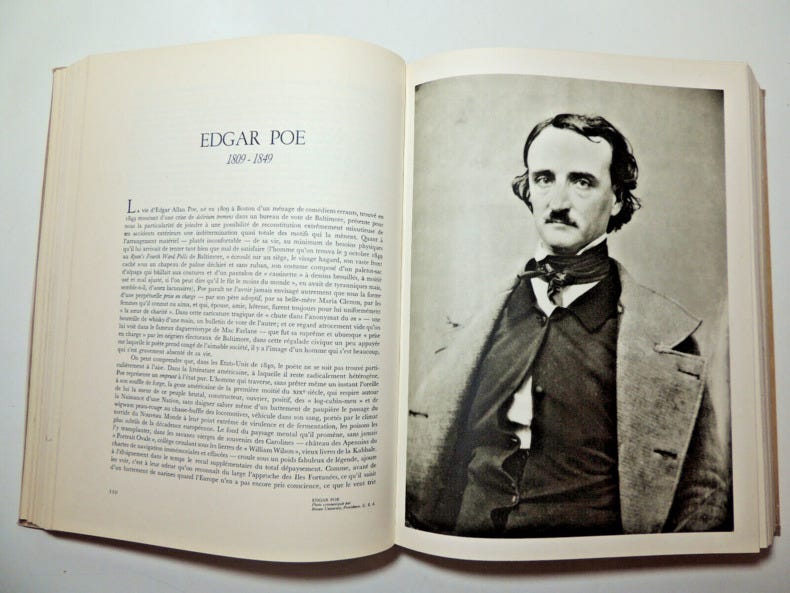

Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to find a photo or scan of Camus’ entry on Melville, though based on a similar series from publisher Lucien Mazenod, I'm guessing it used this photo of him from 1885, then in his mid-60s.

Here’s the layout of the entry on Edgar Allan Poe, as an example:

And finally, here is the essay in its entirety, translated into English as it later appeared in Lyrical and Critical Essays, a collection of Camus’ writing published in 1968. And while I do think it’s worth the time to read in full I’ve also put some of my favorite lines and insights in bold. Amuse-toi!

Back in the days when Nantucket whalers stayed at sea for several years at a stretch, Melville, at twenty-two, signed on one, and later on a man-of-war, to sail the seven seas. Home again in America, his travel tales enjoyed a certain success while the great books he published later were received with indifference and incomprehension. Discouraged after the publication and failure of The Confidence Man (1857), Melville "accepted annihilation." Having become a custom's officer and the father of a family, he began an almost complete silence (except for a few infrequent poems) which was to last some thirty years. Then one day he hurriedly wrote a masterpiece, Billy Budd (completed in April 1891), and died, a few months later, forgotten (with a three-line obituary in The New York Times). He had to wait until our own time for America and Europe to finally give him his place among the greatest geniuses of the West.

It is scarcely easier to describe in a few pages a work that has the tumultuous dimensions of the oceans where it was born than to summarize the Bible or condense Shakespeare. But in judging Melville's genius, if nothing else, it must be recognized that his works trace a spiritual experience of unequaled intensity, and that they are to some extent symbolic. Certain critics have discussed this obvious fact, which now hardly seems open anymore to question. His admirable books are among those exceptional works that can be read in different ways, which are at the same time both obvious and obscure, as dark as the noonday sun and as clear as deep water. The wise man and the child can both draw sustenance from them. The story of captain Ahab, for example, flying from the southern to the northern seas in pursuit of Moby Dick, the white whale who has taken off his leg, can doubtless be read as the fatal passion of a character gone mad with grief and loneliness. But it can also be seen as one of the most overwhelming myths ever invented on the subject of the struggle of man against evil, depicting the irresistible logic that finally leads the just man to take up arms first against creation and the creator, then against his fellows and against himself. Let us have no doubt about it: if it is true that talent recreates life, while genius has the additional gift of crowning it with myths, Melville is first and foremost a creator of myths.

I will add that these myths, contrary to what people say of them, are clear. They are obscure only insofar as the root of all suffering and all greatness lies buried in the darkness of the earth. They are no more obscure than Phèdre's cries, Hamlet's silences, or the triumphant songs of Don Giovanni. But it seems to me (and this would deserve detailed development) that Melville never wrote anything but the same book, which he began again and again. This single book is the story of a voyage, inspired first of all solely by the joyful curiosity of youth (Typee, Omoo, etc.), then later inhabited by an increasingly wild and burning anguish. Mardi is the first magnificent story in which Melville begins the quest that nothing can appease, and in which, finally, "pursuers and pursued fly across a boundless ocean." It is in this work that Melville becomes aware of the fascinating call that forever echoes in him: "I have undertaken a journey without maps." And again: "I am the restless hunter, the one who has no home." Moby Dick simply carries the great themes of Mardi to perfection. But since artistic perfection is also inadequate to quench the kind of thirst with which we are confronted here, Melville will start once again, in Pierre: or the Ambiguities, that unsuccessful masterpiece, to depict the quest of genius and misfortune whose sneering failure he will consecrate in the course of a long journey on the Mississippi that forms the theme of The Confidence Man.

This constantly rewritten book, this unwearying peregrination in the archipelago of dreams and bodies, on an ocean "whose every wave is a soul," this Odyssey beneath an empty sky, makes Melville the Homer of the Pacific. But we must add immediately that his Ulysses never returns to Ithaca. The country in which Melville approaches death, that he immortalizes in Billy Budd, is a desert island. In allowing the young sailor, a figure of beauty and innocence whom he dearly loves, to be condemned to death, Captain Vere submits his heart to the law. And at the same time, with this flawless story that can be ranked with certain Greek tragedies, the aging Melville tells us of his acceptance for the first time of the sacrifice of beauty and innocence so that order may be maintained and the ship of men may continue to move forward toward an unknown horizon. Has he truly found the peace and final resting place that earlier he had said could not be found in the Mardi archipelago? Or are we, on the contrary, faced with a final shipwreck that Melville in his despair asked of the gods? "One cannot blaspheme and live," he had cried out. At the height of consent, isn't Billy Budd the worst blasphemy? This we can never know, any more than we can know whether Melville did finally accept a terrible order, or whether, in quest of the spirit, he allowed himself to be led, as he had asked, "beyond the reefs, in sunless seas, into night and death." But no one, in any case, measuring the long anguish that runs through his life and work, will fail to acknowledge the greatness, all the more anguished in being the fruit of self-conquest, of his reply.

But this, although it had to be said, should not mislead anyone as to Melville's real genius and the sovereignty of his art. It bursts with health, strength, explosions of humor, and human laughter. It is not he who opened the storehouse of sombre allegories that today hold sad Europe spellbound. As a creator, Melville is, for example, at the furthest possible remove from Kafka, and he makes us aware of this writer's artistic limitations. However irreplaceable it may be, the spiritual experience in Kafka's work exceeds the modes of expression and invention, which remain monotonous. In Melville, spiritual experience is balanced by expression and invention, and constantly finds flesh and blood in them. Like the greatest artists, Melville constructed his symbols out of concrete things, not from the material of dreams. The creator of myths partakes of genius only insofar as he inscribes these myths in the denseness of reality and not in the fleeting clouds of the imagination. In Kafka, the reality that he describes is created by the symbol, the fact stems from the image, whereas in Melville the symbol emerges from reality, the image is born of what is seen. This is why Melville never cut himself off from flesh or nature, which are barely perceptible in Kafka's work. On the contrary, Melville's lyricism, which reminds us of Shakespeare's, makes use of the four elements. He mingles the Bible with the sea, the music of the waves with that of the spheres, the poetry of the days with the grandeur of the Atlantic. He is inexhaustible, like the winds that blow for thousands of miles across empty oceans and that, when they reach the coast, still have strength enough to flatten whole villages. He rages, like Lear's madness, over the wild seas where Moby Dick and the spirit of evil crouch among the waves. When the storm and total destruction have passed, a strange calm rises from the primitive waters, the silent pity that transfigures tragedies. Above the speechless crew, the perfect body of Billy Budd turns gently at the end of its rope in the pink and grey light of the approaching day.

T. E. Lawrence ranked Moby Dick alongside The Possessed or War and Peace. Without hesitation, one can add to these Billy Budd, Mardi, Benito Cereno, and a few others. These anguished books in which man is overwhelmed, but in which life is exalted on each page, are inexhaustible sources of strength and pity. We find in them revolt and acceptance, unconquerable and endless love, the passion for beauty, language of the highest order — in short, genius. "To perpetuate one's name," Melville said, "one must carve it on a heavy stone and sink it to the bottom of the sea; depths last longer than heights." Depths do indeed have their painful virtue, as did the unjust silence in which Melville lived and died, and the ancient ocean he unceasingly ploughed. From their endless darkness he brought forth his works, those visages of foam and night, carved by the waters, whose mysterious royalty has scarcely begun to shine upon us, though already they help us to emerge effortlessly from our continent of shadows to go down at last toward the sea, the light, and its secret.

Article published in Les Ecrivains célèbres,

Editions Mazenod, Volume III, 1952

References

Albert Camus, Essais (1965)

Albert Camus, Notebooks 1935-1951 (1998)

Albert Camus, Travels in the Americas: Notes and Impressions of a New World (2023, ed. Alice Kaplan)

Olivier Todd, Albert Camus: A Life (1997)

Herbert Lottman, Albert Camus: A Biography (1979)

Robert D. Zaretsky, Albert Camus: Elements of a Life (2011)

James F. Jones, Jr., “Camus on Kafka and Melville: An Unpublished Letter,” The French Review, Vol. 1, No. 4 (March 1998)

Leon S. Roudiez, “Les Étrangers Chez Melville et Camus,” Configuration critique d'Albert Camus. ; Revue des Lettres Modernes 64-66 (1961)

Jean Giono, Melville: A Novel (trans. Paul Eprile)

Isabelle Génin, “Giono, Translator or Reader of Moby-Dick?", TTR : Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction, Volume 27, Number 1, 1er semestre 2014, p. 17–42