Just when I thought I was done with coffee-related posts, I got pulled back in for one more cup.

Earlier this year I investigated the real reason that the founders of Starbucks named their coffee company after Moby-Dick, and was able to credit the person actually responsible for the iconic branding choice. Now, the world knows that the idea came from their friend Ed Leimbacher, whose passion for the book came from studying American Literature in graduate school.

Regardless, it’s always been the case that the connection between the brand and the book began and ended with the name they share. Apart from some bogus PR copy that connects the book’s ocean setting to the ‘origins of the coffee trade,’ to my knowledge Starbucks has never used any other details, names, or imagery in its stores or marketing, and has wisely avoided reminding its patrons of the whole ‘whale hunting’ aspect of its namesake’s job as first mate.

That is, until just recently.

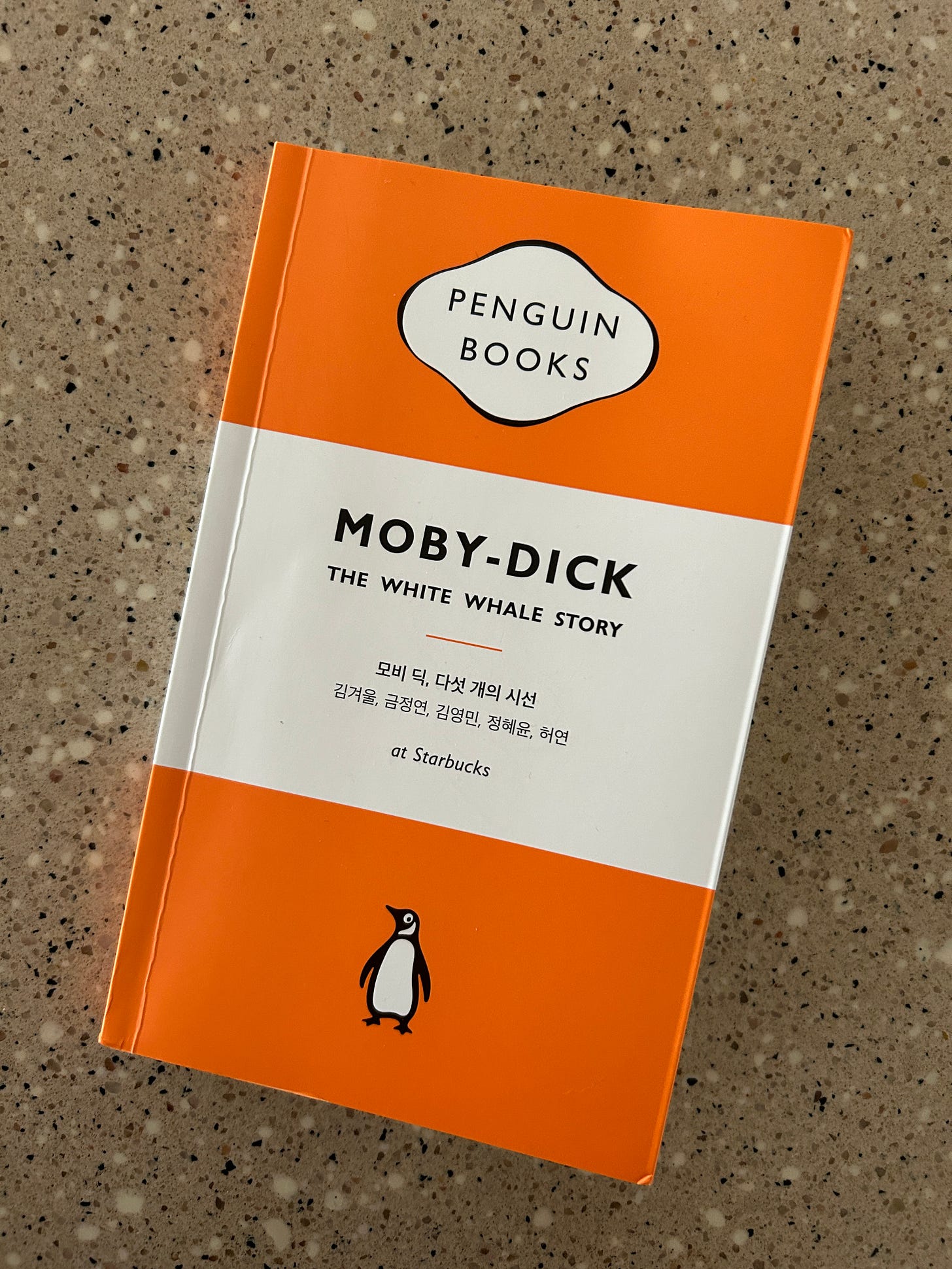

In late August, an automated search alert pointed me to a Reddit post about an upcoming Fall promotion by Starbucks Korea, announcing the introduction of a few new seasonal coffee drinks and snacks, highlighting a theme of chestnut flavorings. Starbucks Korea was also celebrating the 25th anniversary of the chain opening its first store in the country, and used the occasion to collaborate with Penguin Books for a promotion: customers spending over a certain amount were eligible to receive a copy of some sort of Moby-Dick book. From the press release:

Starting on the 6th of next month, a special event will be held where customers will randomly receive one of two books prepared in collaboration with ‘Penguin Random House’ to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the store’s opening.

The company said that customers who purchase over 15,000 won, including a Blonde Coffee drink, will randomly receive one of the two books, ‘MOBY-DICK: Moby Dick, Five Views’ and ‘BOOK & COFFEE Interview: Cafe as a Workshop’, on a first-come, first-served basis.

Specifically, patrons who spent over 15,000 South Korean won (about $11 USD) in September had a 50/50 shot at receiving either a book called Moby Dick, Five Views or another one called BOOK & COFFEE Interview: Cafe as a Workshop. It seemed the idea behind the campaign was Starbucks embracing its image as a place to read and work, and what better book to highlight than the store’s namesake?

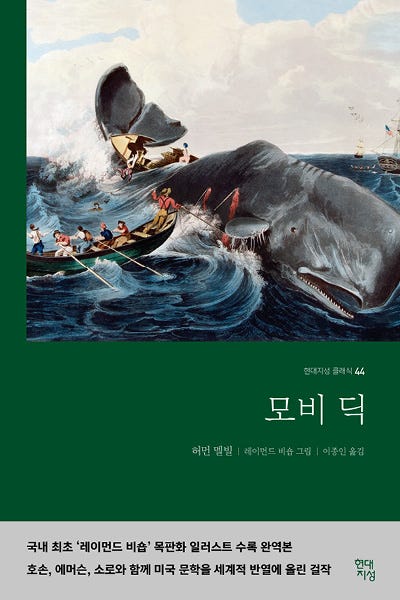

It wasn’t clear to me from the press release, however, whether the Moby-Dick book was some kind of literary criticism, an excerpt, or even an adaptation. (The title, not to mention the sheer length of Moby-Dick, made it unlikely to be a straight translation. A recent translation by by Lee Jong-in from 2022, for example, was over 700 pages.)

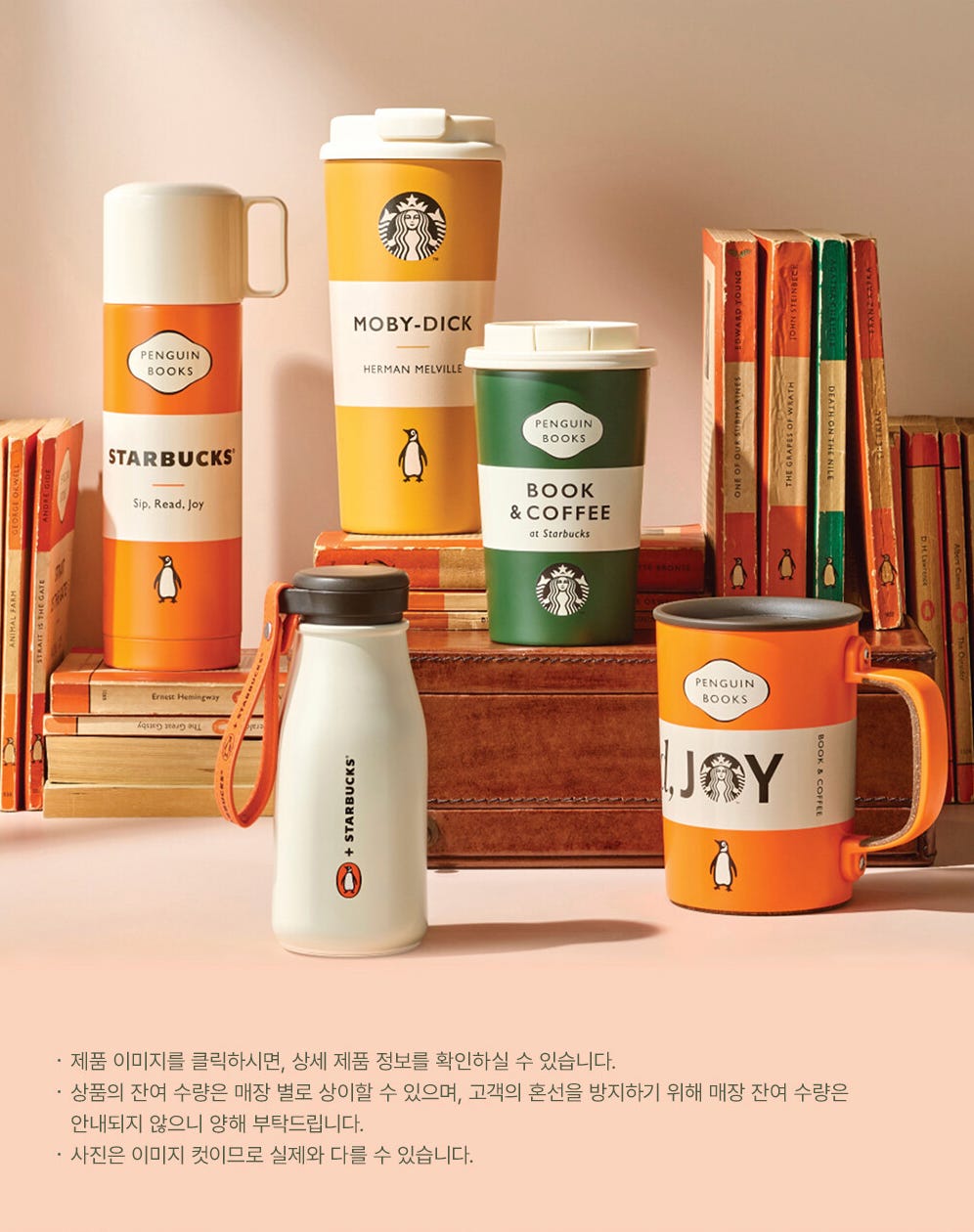

Braving the language barrier with quick web browser translators, I was able to find more information on the website for Starbucks Korea, which said little else about the book but featured a variety of other Moby-Dick themed products. In the image below, for instance, you can see the orange spine of Moby-Dick book on the top shelf on the left, leaning on the green spine of BOOK & COFFEE. You can also see that the book is quite small and perhaps only around 100 pages.

But what you probably noticed first is that to the right of the books is some kind of ceramic box designed as a copy of Moby-Dick. Another image from the website shows a travel mug styled as a copy of Moby-Dick. (Beside it are other Penguin Books titles like The Grapes of Wrath, Death on the Nile, The Trial, and One of Our Submarines by Edward Young.

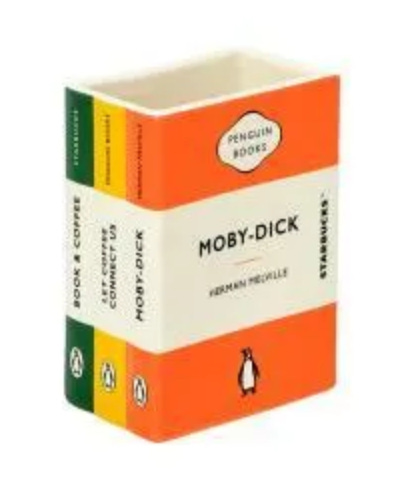

The ceramic box and mug, it turns out, are additional products which you could buy at participating stores. Here, for example, is a closeup of the ceramic box, designed as a set of books with Penguin Books’ “tri-band” design.

[Note: I wouldn’t otherwise share these links promoting the products except that the campaign is long over now, nor was it possible to order anything outside of Korea]

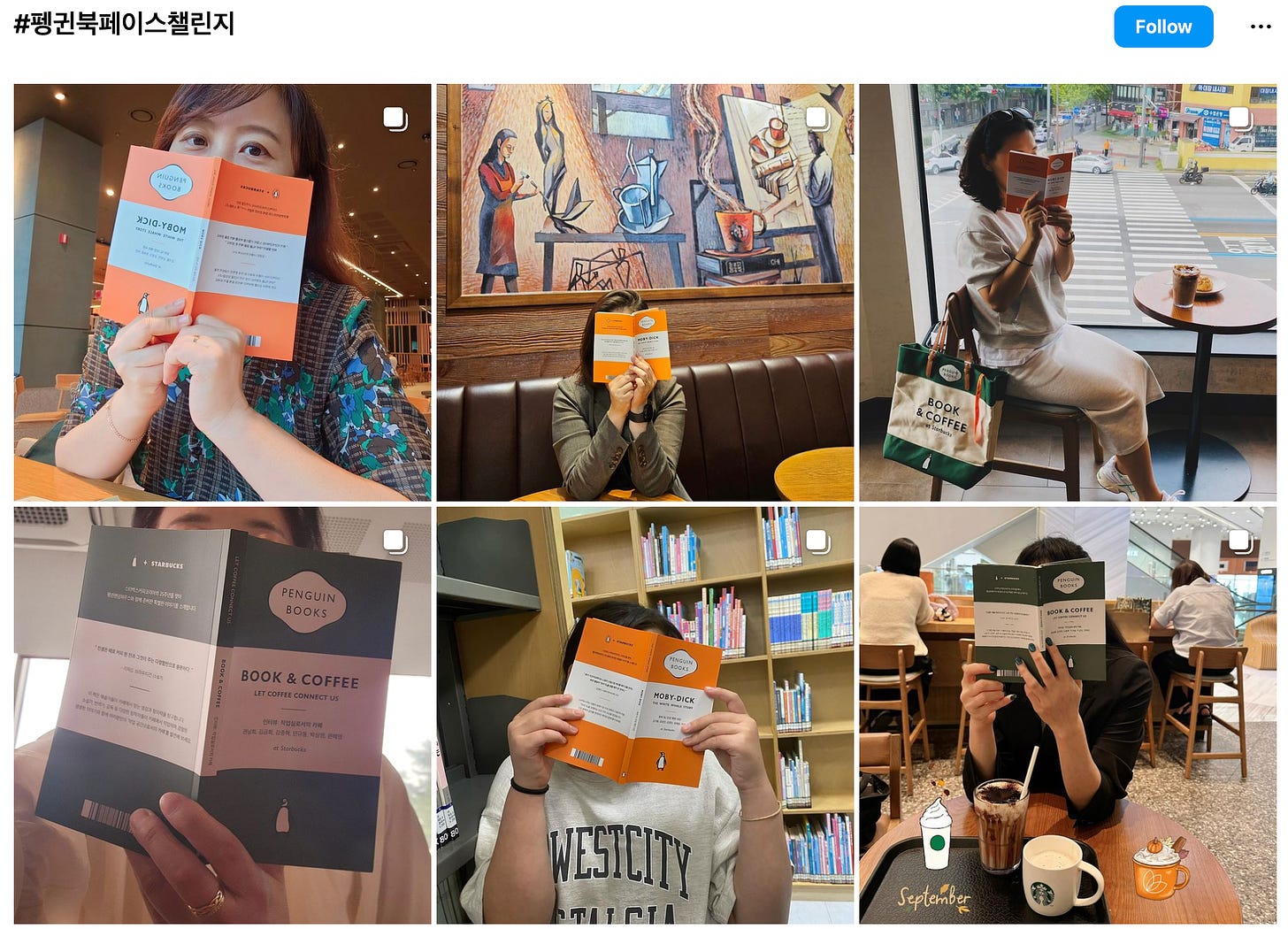

I also discovered that the promotion (naturally) had an associated social media hashtag ‘challenge’ which translated to #PenguinBookFaceChallenge, where people showed themselves reading their copies of the books in cafes.

Nothing on the website or other promotional materials gave any clues about what was actually in that Moby-Dick book, but the title, Moby Dick, Five Views had me intrigued. So, I did what any reasonable person would do: find a stranger in South Korea who was willing to go to their local Starbucks, get a copy of the book, and ship it to me here in the United States in exchange for me buying their coffee and snack. Plus shipping and a little extra to be nice.

A Package from Seoul

A few weeks later, a package arrived on my doorstep.

With the strong caveat that all of this is, again, roughly translated by Google, here’s what’s inside. The book begins with a short biography of Melville with the standard bullet points: his life at sea, a failed literary career, and the revival of his reputation in the 1920s. This is followed by an introduction apparently used in both this and the BOOK & COFFEE editions, mostly just corporate drivel about how the “fragrant aroma of coffee, the warm welcome, the spacious and comfortable space, and the feeling of leisurely sitting and drinking coffee in the midst of moderate white noise are irreplaceable” and make for ideal spots to read.

Another few pages of introduction repeats the largely untrue story about the founders and the naming of the company, plus — at last — the aims and structure of the book:

This book was planned with the founder's heart to provide people with small adventures and moments of travel in their everyday lives through a cup of coffee. Five writers working in the field talk about Moby Dick from their own unique perspectives. Through this book, they want to convey how colorful and fascinating Moby Dick is. I hope this book will provide new inspiration and deep insight to readers.

With this, I was finally beginning to understand what it is I was looking at. In effect, it’s an anthology of five essays that make up a sort of Korean “Why Read Moby-Dick?” (and which, I found out, namecheck Philbrick’s book several times). While this is about what I expected based on the title, I was interested to see how an entirely different culture not only approached the book, but explained it to others in their cultural context. What elements and themes ‘translated’ from the American idiom and experience to that of South Korea? How do the essays reflect an interpretation of Moby-Dick as representative of the United States, itself?

The titles of the essays alone gave me a sense that the takes might be slightly askew from the normal slate of interpretations (plus or minus some translation wonkiness). The ‘five views’ are:

Kim Gyeoul, “Moby Dick: Everyone Knows But No One Knows”

Geum Jeong-yeon, “A Ghost is Wandering the Seas. A Ghost Named Moby Dick”

Kim Young-min, “See Moby Dick, Face Life”

Jeong Hye-yoon, “Chasing Moby Dick”

Heo Yeon, “Another voyage awaits forever”

I won’t go too deep into each essay, but so long as I went to the trouble of getting this book from halfway around the world, I thought it was worth translating all 135 pages and providing some highlights.

Kim Gyeoul (김겨울), “Moby Dick: Everyone Knows But No One Knows”

The first essay is by author, musician, poet, public speaker, and radio book club host Kim Gyeoul, who sometimes goes by her anglicized name Winter Kim. She’s perhaps best-known now as being a major Korean “BookTube” influencer with nearly 300,000 subscribers to her YouTube channel Winter Bookstore.

Kim provides a kind of Moby-Dick 101, introducing the main characters, themes, and some low-hanging fruit of the symbolism used throughout the book. Appropriately, Kim writes in the style of an influencer/book reviewer, distilling the experience of reading the book for her readers/viewers.

When you read this novel not just with your eyes but with your whole body, you will feel as if you were sailing the sea with them and being turned over by the waves, as if you witnessed a huge white whale right before your eyes, and you will feel the saltiness of the sea on your tongue, and you will be overwhelmed by a burning desire for revenge, the futility and despair of a shipwrecked life, and finally a small sense of relief when you finally set foot on land.

The title of the essay, “Moby Dick: Everyone Knows But No One Knows,” refers both to the way that the basic elements of the novel are widely known even to those who haven’t read it, and also to Ishmael’s preoccupation with epistemology and the futility of pursuing either ultimate knowledge (in the case of Ishmael) or ultimate power (in the case of Ahab) to an extreme.

What I read in Moby Dick was the inevitable fate of man. That we cannot conquer, destroy, or overcome what blinds us, what limits our lives. That is our situation, and that any attempt to escape from it is noble and beautiful, but at the same time foolish and arrogant.

The important thing is that neither Ishmael, nor Ahab, nor anyone else in the novel ever fully sees or conquers the whale. In the last paragraph of Chapter 32, "Cetology,” is this sentence: "God keep me from ever completing anything." The idea that we can have a complete understanding of whales is nothing more than a human delusion… At first glance, it seems like a chapter that organizes all knowledge about whales, but in fact Ishmael is saying: We do not know whales. We travel the seas to catch what we do not know. […]

Can humans understand everything in the world? Our science and technology tell us that day will come… But no matter how much more we know, even if we know, there is a fundamental epistemological limitation that we can never overcome. Humans cannot even answer accurately whether the world we see, experience, and calculate is the real world. This is because no human being can overcome the fundamental limitation of sensing the world under fixed physical conditions and calculating the world with reason. However, Ahab wants to take off Moby Dick's 'mask'. He hates the great power that Moby Dick possesses. In other words, he wants to see through the essence beyond the mask, what on earth makes the world like this.

It’s a surprisingly deep analysis for what might be many readers’ first exposure to the actual content of the book. The essay ends by encouraging readers to take on and engage with Moby-Dick despite its admittedly daunting length, emphasizing that they’ll be rewarded should they leave their assumptions behind.

Geum Jeong-yeon (금정연), “A Ghost is Wandering the Seas. A Ghost Named Moby Dick”

Winner of the best title of the lot is author and literary critic Geum Jeong-yeon. With the basics of the novel covered by Kim, Geum can go a bit deeper into the plot and notable scenes, such as Ahab’s quarter-deck speech, the doubloon, and even the Etymology and Extracts chapters, explaining that “Just as small barnacles are attached to the body of a huge whale, 'Moby Dick' also has numerous side stories attached to it.” He also provides background on Melville’s writing process and relationship with Nathaniel Hawthorne.

The essay, however, takes a turn when Geum offers some of his impressions from when he first read Moby Dick 13 years ago, admiring the writing style but comparing the experience reading the back half of the book to something like hurriedly bailing water from a boat.

After a hundred pages of teasing, he finally got him on board, and before long he was into a sort of biological report on whales… filling the pages with miscellaneous knowledge of the whaling ship's system, which would surely be of great use if you were ever sold to a fishing boat. One hundred pages, two hundred pages, three hundred pages, four hundred pages... To be honest, it wasn't so exciting that you'd go crazy. Although, if you'd majored in philosophy or theology, you might have been a little out of breath when it came to speculating about religion, God, and destiny.

At one point, I felt a little bit self-destructive. And like a sailor who is stranded at sea and gulps down seawater because he can't stand the thirst, I started reading the remaining pages of Moby Dick in a hurry. It wasn't that hard. Melville's writing style, which was solid but also light, often humorous, and sometimes even beautiful, captivated me. With that kind of writing style, I thought I could read through the long garbage about the 'Terms of Service' and 'Personal Information Collection and Use' of a website in one sitting.

Here, Geum’s essay runs out of steam, perhaps reliving some of that earlier exhaustion with novel’s 1,000 pages. Instead of giving his own reasons that his audience should read Moby-Dick, he says he intends to “imitate Ishmael once again” by simply listing some famous Melville fans and, a la Extracts, quotes them directly and fills several more pages.

Worse, he ends with a reflection Darren Aronofsky's 2022 film The Whale and its, let’s say, highly questionable theory that Melville included “the boring chapters that were only descriptions of whales, because… the author was just trying to save us from his own sad story, just for a little while.” Like the character of the teenage daughter who wrote the essay, it leaves the impression that maybe Geum didn’t finish the assignment for a second time around.

Kim Young-min (김영민), “See Moby Dick, Face Life”

Kim Young-min’s “See Moby Dick, Face Life” takes a decidedly existential or even morbid look at Moby-Dick. Kim is described as a writer, a researcher of the history of thought, and a professor of political science and diplomacy at Seoul National University. His published work includes things like “History of Chinese Political Thought” but then also prose collections with titles like “It is Good to Think of Death in the Morning” and “Living as a Human is a Problem.” So you kind of get a sense of where he’s coming from.

Without any preamble, Kim’s essay begins with this attention-grabbing riff on Ishmael’s own self introduction, given the subtitle: “The time has come.”

The lyrics of the song say people are more beautiful than flowers. Lonely people say they miss the smell of people. Is that really true? Are people more beautiful than flowers? Are these vile people more beautiful than those flowers in full bloom? Do you miss the smell of people? Do you miss the smell of that dirty skin? Really? There will be times when you have such unpleasant thoughts in your life. There will be times when you feel sick and tired of something. It is time to read Herman Melville's 'Moby Dick' while lying in the Dead Sea.

Kim’s thesis overall is that Moby-Dick is a book not just about self-destruction, but about intentionally heading toward self-destruction, something he sees being depicted by both Ahab and Ishmael. “It is about willingly going out to the ocean in search of the truth while enduring death rather than continuing to live amid unnecessary stimulation, anxiety, and confusion.”

Discussing lines from the book like when Ishmael decides to write his will after the first chase, and how all men live “enveloped in whale-lines,” Kim writes about the ways our lives change after we face death and “resolve to die.”

If the new life that unfolds after resolving to die is the key, then whether or not you actually die is not important. What is important is facing death, being conscious of death, and resolving to die… In this way, when you resolve to die, you experience something bigger than yourself. In that experience, you feel that you are just a trace or fragment of a bigger and better existence.

That feeling, he writes, is the same reason we choose to read classics like Moby-Dick, pursuing a “small death of the mind” and abandoning the worldview with which we began the book. He likens the process to kintsugi, the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery: reading for information or pleasure merely fills a vessel; reading classics breaks the vessel wide open.

Reading classics is not just reading to update knowledge, reading for information, reading for comfort, or reading to pass the time. When people read to get information, to find comfort, or to pass the time, they are filling their mental vessels. I am looking for pretty or useful things to put in. However, reading classics is different. Classics are not books to be read to find things to put in a vessel, but to break open a vessel. Only after a vessel is broken can a new vessel be made. That new vessel is not a completely new vessel, but an old vessel that has been expanded through wounds.

Kim goes on to talk about whales and the boundlessness of the ocean, the human condition, and “mortal greatness” as Ishmael puts it, finally landing on Ahab’s pasteboard mask concept and his fear that “there’s naught beyond.” The translation here, I admit, gets a little wonky, but asserts that even if Ahab is right, that place beyond the mask is necessarily a “less vile” and “freer place.”

Let's say we somehow manage to come face to face with a white whale. Let's say you succeed in facing the Great Wall of China that surrounds your life. What is there beyond that wall? … Yes, there may be nothing beyond that wall. Behind the white whale, there's another white whale.

A white whale may be waiting behind it, and another whale may be waiting behind that white whale, and an emptiness even greater than the whale may be waiting behind the last white whale. Can freedom from the bondage of meanness be only sweet?

Even if that place is an empty place, it is a wider place beyond the narrow self, a place closer to the whole. It is not a place where one's own self, quietly waiting for someone to find it, is enshrined. Rather, it is a place where the fragments of a broken self are scattered. So how scary that place is. However, it is a less vile place than here now, where sweet words run rampant, and thus a freer place.

Jeong Hye-yoon (정혜윤), “Chasing Moby Dick”

Fourth up is Jeong Hye-yoon, described as a radio DJ and podcast host whose work focuses on grief, bereavement, and survivors of tragedies. Her “Voice of 416” podcast, for example, interview the families of the Sewol ferry disaster victims. She’s also made documentaries such as “The Secret of the Suicide Rate,” “Gifts from Those Left Behind,” and “75 Years of Solitude of the Korean War Criminal,” which won the Korea Broadcasting Award for Best Work.

As with Kim Young-min, this background seems to inform Jeong’s essay which uses the framing device of a personal conversation with a friend whose life is lacking direction. “I feel like I've fallen apart," they say, and ask if Jeong had ever read Moby-Dick. “What am I chasing? I need to find an answer.”

Jeong had read Moby-Dick some years earlier, but had a decidedly different takeaway from the book. The friend apparently envied Ahab’s self-assuredness in his mission and purpose (however insane). Jeong, though, was enchanted by Ishmael’s more ethereal musings such as when he and Queequeg are weaving the sword-mat, quoting from Chapter 47: “Such an incantation of reverie lurked in the air, that each silent sailor seemed resolved into his own invisible self.” She relates to this zen-like feeling of “melting into the sunlight.”

On a beautiful day, I feel like I am melting into the sunlight, melting into the scent of acacia, into the wind that caresses and comforts, into the heart-wrenching sunset, into the distant starlight. I know that I am happy then. I know that I am enjoying the moment. I wish for nothing else than to be there at that moment. To be exact, I do not know what else to wish for. I think that just being there in that moment, with my hair blowing in the wind, is worth being born and worthwhile. At that moment, my soul seems to be purified and distilled much more than my real self, and my many selves are on good terms without conflict. To me, ‘melting’ is synonymous with happiness.

Perhaps to the friend’s chagrin, that somewhat philosophical, intangible, and not particularly goal-oriented tone is fairly representative of the rest of the essay and Jeong’s approach. That is, Moby-Dick is more of an occasional touchstone for the essay rather than its focus, careening off various elements of the book to discuss things like the pursuit of meaning, major life choices, and intention in our actions. To what degree it might convince someone to read Moby-Dick, however, I’m not so sure. Jeong’s head is very much in the clouds, aloft in the mast-heads and, like Ishmael, only rarely looking for whales and ‘keeping but sorry guard.’

Heo Yeon (허연), “Another voyage awaits forever”

Finally, the book ends with an essay by poet and journalist Heo Yeon, who has won several national and industry awards and contributes articles on literature and the publishing industry for Korea’s Maeil Business News. Yeon recalls his first encounter with Moby-Dick as a child in the form of movie adaptation airing on Korean television. Writing in third person, he remembers surreptitiously watching the movie one night.

As a child, when the signal music of “Masterpiece of the Week” flowed out on the television, the boy would start to dream. His mother was a sage who made him go to bed early, but the boy would stick his head out of the blanket and watch movies. One of the movies he came across that way was “Moby Dick.” This movie, which was broadcast under the name “Baek-Kyung,” was truly amazing. […]

Moreover, the names of the characters were out of the ordinary from those he heard during catechism classes at the cathedral.

The next day, he ran to the bookstore in front of the school and bought the children's novel, Moby-Dick. It led the boy, who lived in a small house in a small country, to a wide world he had never been to before.

Heo’s essay looks at the novel through a handful of notable scenes which stuck with him from the movie he saw as a child, despite reading it several more times as an adult: befriending Queequeg in New Bedford, Ahab’s quarter-deck speech, the final chase, and so on. One can learn to compare elements of the book to its peers in Shakespeare's major tragedies, he says — the abuse of power and downfall of King Lear, the madness and obsession of Macbeth, and the revenge of Hamlet — but a formal education can’t replace feeling of what excited him about the story while hiding under blanket.

Primarily, though, Heo’s essay is concerned with Melville’s core value of a “human-centered equality” depicted in Ishmael’s solidarity (and even oneness) with the crew. He even finds room for a brief explanation and analysis of "The Portent,” Melville's poem about abolitionist John Brown from Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War.

The narrator of the novel, Ishmael, criticizes the desires and corruption of human society, and at the same time demands a new reflection on God by putting forward the symbolic existence of Moby Dick. In particular, Moby Dick contains the core values of human-centered equality that shook the United States since the time of the Civil War. Melville talks about solidarity and equality that transcends race and religion, and this had a great impact on society at the time. […]

He [Ishmael] boldly speaks his opinion against the others and develops a friendship with the unwelcome Queequeg. Furthermore, he is portrayed as a character who strives for community solidarity among the crew of the Pequod. Ishmael is a character who was pushed out of society and joined a whaling ship, but he is a pure and forward-thinking reformist character.

Heo ends with a coda to the essay and to the book as a whole, returning to the question of how and why Starbucks chose its name, quoting from the company’s website. As I did, he questions the authenticity of the claim that the name was meant to ‘evoke the seafaring traditions of early coffee merchants’ as the company states. Instead, he offers his own interpretation, tying Starbuck’s demeanor and sense of reason to the calmness one finds in a cafe.

In the novel, the whaling ship is a place of madness seething with desire. Melville introduces a wise and rational person to that place of chaos, and that person is Starbuck. Perhaps the world we live in is a giant Pequod. Every day, fierce debates, conflicts, challenges, and defeats are repeated, and mankind shouts faster and higher toward greater desires and goals. Perhaps the Starbucks founders wanted to emphasize the charm of a cup of coffee that brings reason and peace like a skilled navigator in a complex and chaotic world (a whaling ship). Melville created his own literary republic, but unfortunately in his time, there were not many citizens of the Republic of Melville. But now, nearly two centuries later, we are all becoming citizens of the Republic of Melville. Drinking Starbucks coffee every day, we find a moment of reason and peace.

The rationale might give the company’s founders some undeserved credit, but credit nevertheless to Heo Yeon for trying to make sense of this strange little book which is equal parts informative and bewildering — maybe in just the right blend to make readers interested enough to pick up a copy of 모비 딕 for themselves.

Wow, you really go the extra mile! I was (incorrectly) thinking 5 Views was just going to be excerpts from the book. Now my curiosity is thoroughly satisfied. By the way, I looked for the M-D Starbucks tumbler online, but unfortunately it can’t be bought for less than around $60.