Dollars Damn Me

; or, was Melville "paid by the word"?

As part of my research to find new topics to write about here, I like to keep an eye out for discussions on social media about Melville and Moby-Dick. I’m always curious what regular people have to say about their reading experience and what observations they have, especially those which might never occur to someone who’s maybe too familiar with the book. Then there are the perennial complaints that the less plot-driven chapters bored them to tears, the imaginative speculation about Melville’s keen ‘admiration’ for Nathaniel Hawthorne, and the shock at how light and funny the whole thing contrary to their preconceptions.

But there’s one particular, pernicious claim made so often about Moby-Dick, or rather about Melville himself, that I thought it was worth exploring if only to make sure there wasn’t some kernel of truth behind it. I was also curious to see if I could figure out how so many people have come to believe the same falsehood; namely, that Moby-Dick is so long, and includes so many extraneous chapters about whales and whaling, because Melville was “paid by the word.”

Here’s just a small sampling of what comes up with you search for “Melville” and “paid by the word” on Twitter and Reddit, where people regularly make this claim and, unfortunately, pass it on to others:

What’s worse is that some of these people recall learning it directly from their teachers and professors.:

Nor does it help that there are answers on sites like Quora.com where its prolific users repeat the idea, confidently stating that Melville included a “textbook on whales and whaling” as a “good way to pick up some extra cash from his publisher.”

I even found that the idea had been published in newspapers, for example in the Greenwich (Conn.) Time in October 1991:

Going into the research I felt 99.9% sure that there was no truth to the idea; that he had no contract with publishers until the very last stages of finalizing the text, and ultimately was hardly paid anything at all for Moby-Dick, much less any number times its ~200,000 word count. But still, I wanted to make sure that I wasn’t spreading misinformation, myself.

What the Dickens?

I think for many people, myself included, the phrase “paid by the word” brings to mind another 19th century author who, like Melville, many encounter for the first and last time in high school: Charles Dickens. Whether this claim also came from misguided teachers or was simply teenager lore passed down by each generation, I remember hearing this myself and feeling indignant at the idea that every convoluted courtship or belabored description of some waif being run over by a carriage was merely Dickens’ busywork which, 150 years later, had become my busywork. And while I don’t share the sentiment, I can appreciate that someone who hasn’t enjoyed the first 31 chapters of Moby-Dick likely won’t be thrilled by what lies in store. So I can hardly blame someone for pulling their hair out and wondering if this is all some sort of sick joke.

Melville and Dickens aren’t alone in this, either. Other 19th century contemporaries regularly accused of padding their stories include Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and Henry James. It seems that any author from this period with tendencies toward rambling is suspect, often with the implication that we should toss out the work of any author found (gasp) writing to earn a living. (I’ll set aside the larger questions here concerning art, commerce, authenticity, and so on, though it’s worth pondering what’s really being demanded by those insisting that a writer turn down a theoretical offer to write more to earn more.)

But that’s not to suggest that there’s no element of truth to the accusations. Dickens was not paid by the word, no matter how often students whisper it down the hallways. He was, however, paid by the installment. As I think is common knowledge, all of Dickens’ novels were originally serialized in monthly magazines. Each book was divided into twenty installments of a standardized length: thirty-two pages of letter press, two illustrations, plus advertisements filling out each issue. According to the Dickens Project at the University of California, this arrangement at the time benefitted the author, publisher, and readers alike:

Dickens's 20-part formula was successful for a number or reasons: each monthly number created a demand for the next since the public, often enamored of Dickens's latest inventions, eagerly awaited the publication of a new part; the publishers, who earned profits from the sale of numbers each month, could partially recover their expenses for one issue before publishing the next; and the author himself, who received payment each time he produced 32 pages of text (and not necessarily a certain number of words), did not have to wait until the book was completed to receive payment.

Of course, this is something of a generalization of his publishing process and glosses over many details which further complicate the ‘paid by the word’ charge. For instance, two of his most famous novels, A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations, were serialized in a literary journal that Dickens owned, making the question of who was paying who what something of a moot point.

There’s an element of truth in the claim about Dumas, as well, who took advantage of French newspapers which paid by the line. Per one biography, this tactic directly inspired the character of Grimaud, Athos’ pithy valet in The Three Musketeers who would answer questions with a single word. That is, after his short reply Dumas would then move down to the next line and collect another sou (or whatever the going rate was). Newspapers printing his work eventually decided that they wouldn’t pay for any line that didn’t extend to over the halfway mark of the column, and Dumas responded by killing off Grimaud, allegedly telling the editor of Figaro, “I only invented him as a fill-up… he’s no good to me now.” Dumas later denied (or perhaps sidestepped) the accusation altogether, stating “I do not write for La Presse ‘by the line’ but for my own pleasure.”

Was Melville Paid by the Word?

So while “paid by the word” might be shorthand for a slightly more complicated reality, it’s not too surprising that people would believe that this might also have shaped the writing of Moby-Dick. And yet, in this case we can answer without hesitation: no, of course he was not. Not only are the details of when Melville composed Moby-Dick well understood, so is the process by which he sold the book as it neared completion. And at no point was he offered additional payment or returns on profits to extend the length of the book.

In short, Melville returned home from a trip to Europe in February 1850 and likely started writing Moby-Dick soon after, holed up in his house on Fourth Avenue in New York. Although we have a few hints of what might be references to the early days of its composition, his first definitive reference comes from a May 1, 1850 letter to Richard Henry Dana, Jr., telling him “It will be a strange sort of book.”

About the “whaling voyage” — I am half way in the work, & am very glad that your suggestion so jumps with mine. It will be a strange sort of book, tho’, I fear; blubber is blubber you know; tho’ you may get oil out of it, the poetry runs as hard as sap from a frozen maple tree;— & to cook the thing up, one must needs throw in a little fancy….

About two months later, on June 27, 1850, Melville wrote to Richard Bentley, his publisher in London, to inform him of the coming novel and to propose an arrangement of £200 up front plus half of the profits, double what he’d received from Bentley for White-Jacket.

In the latter part of the coming autumn I shall have ready a new work; and I write you now to propose its publication in England.

The book is a romance of adventure, founded upon certain wild legends in the Southern Sperm Whale Fisheries, and illustrated by the author’s own personal experience, of two years & more, as a harpooneer.

Should you be inclined to undertake the book, I think that it will be worth to you £200.

The book was not completed by that autumn as anticipated, and it wasn’t until April 1851 that he reached out to his American publisher, Harper & Brothers, offering the book at their usual rate of half-profits. He also used the occasion to ask for an advance on those profits, which the Harpers soundly refused on account of Melville owing them nearly $700 from losses on his previous books. In other words, still in April 1851 as he neared the finish line he had no contract and certainly no offer to be paid by the word.

Finally, in June 1851 he wrote to Nathaniel Hawthorne that he would be leaving for New York City to work in isolation to complete the book, and to oversee the process of “driving through the press,” creating printing plates of the finalized pages which he paid for out of his own pocket. In other words, given that he had still had no contract or even advance, if Melville was incentivized at all in regard to the length of the book, it was arguably to keep it shorter.

At the end of what biographer Hershel Parker describes as the "intense final phase of intermingled composition and proofreading" in New York, Melville reached out to Bentley and again proposed a £200 advance and half of the profits. Bentley countered with £150, which he accepted. The proof pages were sent overseas to Bentley on September 10, 1851, two days before signing a second contract with Harper for half-profits — and no advance. All of this is to say that Melville had no prearranged contract to write Moby-Dick and earned nothing by adding chapters or reaching a particular length. In fact, the only payment he received prior to any sales of the finalized book was a £150 advance on his profits from Bentley.

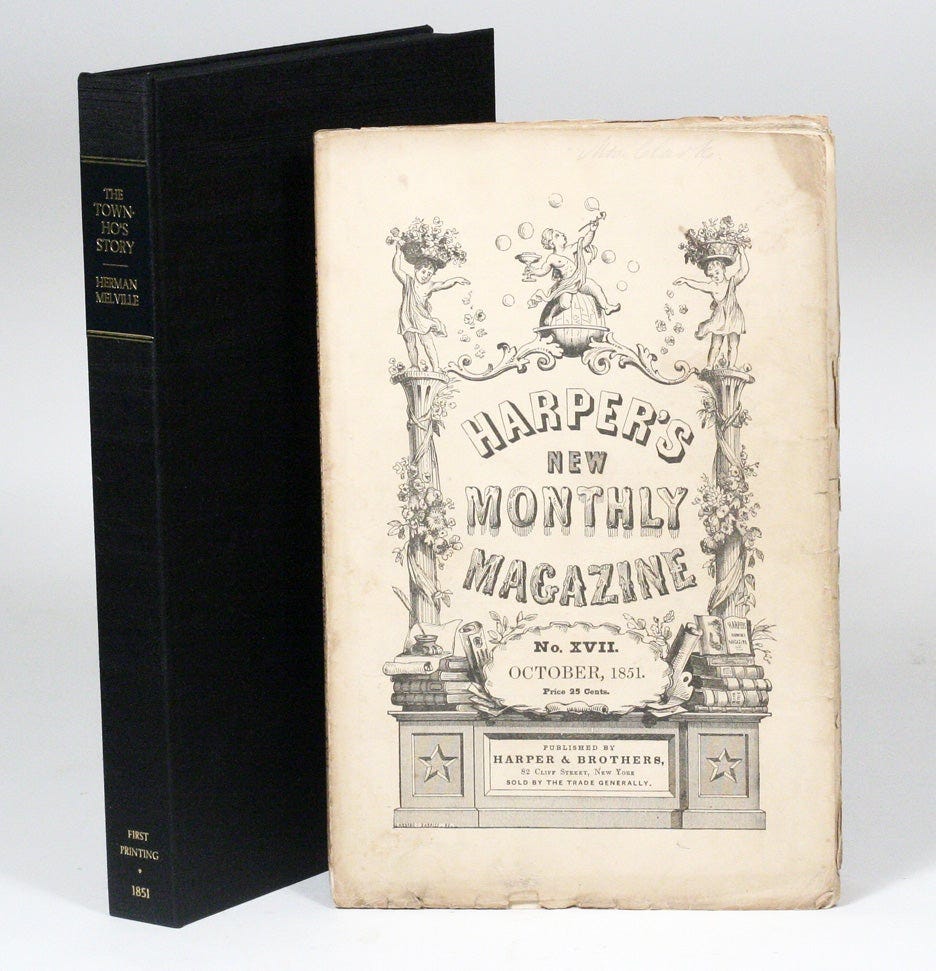

Crucially, Moby-Dick was also never serialized liked Dickens’ and Dumas’ novels were were. One chapter, The Town-Ho’s Story, was published in the October 1851 issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine as a kind of teaser for the forthcoming novel, though Melville wasn’t paid for its use as far as is known.

Melville the Magazinist

But that’s not really the end of the story. Although it’s not exactly what people have in mind when they’re complaining about yet another chapter about whale anatomy, it’s not entirely accurate to say that Melville was never paid by the word — at least loosely speaking. After all, Melville wrote much more than Moby-Dick, and much more than just novels. For this question, we’ll need to examine an often overlooked period of his life when Melville was reeling from the commercial failure of Moby-Dick and its follow-up, Pierre, and eked out a living writing short stories for literary magazines.

Although Melville isn’t well-remembered today as a magazine contributor, even in the mid-1850s he wasn’t new to publishing in newspapers and periodicals. In fact, the first identified piece of his writing published anywhere came in 1838 in the Albany Microscope, which published three letters from the then-19-year-old concerning his local debate club, the Philo Logos society. He also submitted several fiction pieces to the Lansingburgh Democratic Press shortly before leaving for his five years at sea in 1839.

Even after becoming somewhat famous (or perhaps notorious) for Typee, Melville continued writing for various periodicals. In March 1847, he reviewed J. Ross Browne’s Etchings of a Whaling Cruise for his friend Evert Duyckinck’s Literary World journal (no record of payment has survived). While working on Mardi, he contributed a seven-part series of comic sketches about Zachary Taylor’s exploits in the Mexican-American War to the New York humor magazine Yankee Doodle. Once again, though, I’ve found no record of what or how Melville was paid for the series.

Nor does any record of payment survive for reviews he contributed to Literary World after completing Redburn and White-Jacket, or for the pivotal “Hawthorne and his Mosses” essay reviewing Hawthorne’s short story collection Mosses from an Old Manse. Then again, Duyckinck, who was staying with Melville in Pittsfield while he read the collection and began the review, did send him a dozen bottles of champagne and two cigars, though this was presumably a thank you for the hospitality. Yet we might think of Melville having been ‘paid by the bottle.’

To get to the bottom of this question, we have to skip ahead to the years following the lukewarm reaction to Moby-Dick and the dismal reception of Pierre, published in July 1852. Only a few years earlier, Melville had politely declined a request from Duyckinck to contribute to yet another one of his ventures, Holden’s Dollar Magazine. “I can not write the thing you want,” he told Duyckinck. “I am in the humor to lend a hand to a friend, if I can; — but I am not in the humor to write the kind of thing you need.” His dejected tone signals the internal conflict he was working through in the early 1850s, between writing what he wanted versus what would pay. “Dollars damn me,” he famously confided to Hawthorne. “What I feel most moved to write, that is banned,—it will not pay. Yet altogether, write the other way I cannot.”

After the failure of Pierre, the decision was made for him. In 1853, he accepted an invitation to contribute a story to Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, anonymously publishing the short story “Cock-A-Doodle-Doo!” in November of that year. The same month, Putnam’s Monthly Magazine published the first of two installments of “Bartleby, the Scrivener.” For the former, there is yet again no record of payment, so the trail starts with Bartleby, for which Putnam offered Melville $5 per printed page, or $85 for the 17 full pages of text. Only a year earlier Putnam was offering contributors $3 per page, indicating that despite his commercial failure as a novelist, Melville was nevertheless highly regarded as a writer. According to Melville scholar Merton M. Sealts, Jr., the offer was also part of a strategy by the magazine editors to attract more American voices, who in 1850s were still in the shadow of their British peers:

Successful magazines of the 1850’s could afford to be generous to their ablest contributors, and whatever Melville’s current standing as a writer of books, Putnam and the Harpers obviously regarded his magazine pieces as worth bidding for at a premium. Harper’s Monthly, which had begun publication by levying heavily on English materials, needed to meet the challenge of its younger rival by introducing more American contributions….

Being paid by the page gets us closer to finding some truth in the idea, but we might be able to get even closer. In May 1854, Melville received a check from Harper & Brothers for $100, which he marked in his records as being advance payment for four more short stories which ran in Harper's New Monthly Magazine starting with “Poor Man’s Pudding and Rich Man’s Crumbs” in June 1854. This was followed by “The Happy Failure” in July 1854; “The Fiddler” in September 1854; and finally “The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids” in April 1855.

Sealts suggests that Melville’s $100 payment was “evidently calculated on the basis of total wordage rather than by the printed page unless these pieces had actually been set in type by this time” (emphasis mine). There’s a bit of guesswork here, but the logic is that Melville would have to have already completed all four stories by May 1854 when he received the advance payment, but also have sent them to Harpers to be typeset with enough time for the first story to go to print in June. Otherwise, how could Harpers have known the total number of pages once they were set in type? It suggests that payment might have been based on the final word count instead. On the other hand, the total page count “ran to 19 ½ pages in all,” still working out to about his usual rate of $5 per printed page. So maybe Harper’s estimated the pages from the word count? The exact arrangement seems to be lost to history.

Melville was nevertheless determined to write longer pieces, having evidently earned back some trust from his publishers. A novella, The Encantadas, was printed in three installments from March to May of 1854, for which he received $50 per installment. Putnam published an even longer piece, Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (a short novel, really, at 60,000 words) released in nine installments ending in March 1855. Putnam again paid Melville $5 per printed page, for a total of a little over $400.

His contributions to magazines continued through 1856, including Benito Cereno, which concluded with Putnam publishing six of the short stories in a collection titled The Piazza Tales. Thus ended Melville’s era as a magazine writer, which included not only some of his most celebrated stories (and some of his most underrated) but restoring his confidence as a writer. Sealts estimates Melville’s total earnings for his magazine work at $1,329.50, all — or nearly all — of which was paid by the page.

The Scrivener

Ironically, it’s Bartleby who was most likely to be paid by the word, as professional scribes generally were at the time. In fact, it wasn’t Dickens and Dumas who were the most frequent targets of grumbling about being paid by the word but lawyers and law offices, accused of being longwinded for the sake of extracting more money from clients. There’s a entire Wikipedia page dedicated to the “Legal Doublet,” standardized redundant language which are thought to have come from clerks who were paid by the word. Hence phrases like null and void, aid and abet, for all intents and purposes, signed and sealed, and so on — all of which say nothing with two words that they didn’t say with one.

For instance, here are two short 'squibs’ from the late 1800s about the issue, one from Missouri’s Centralia Fireside Guard in 1899 and another from the St. Paul Globe in 1885.

All that said, I doubt that anyone who has ever accused Melville of being paid by the word had in mind his short stories, even if there’s at least some slight truth to it there. Melville’s highly-productive magazine years arguably demonstrates just the opposite, really. Between 1853 and 1856, Melville published no less than 15 short stories, a novella, and wrote four novels (Israel Potter, The Confidence Man, and two more that ultimately went unpublished). In other words, Melville could hardly be accused of belaboring any individual story in order to exploit his publishers; as soon as one story was finished he quickly moved on to the next one, trying desperately to stay financially afloat. What’s more, his relationship with his publishers, who repeatedly lost money on his novels, may have been simply too tenuous for Melville to try to pull one over on them by submitting needlessly padded stories.

How the myth came to be in the first place we can only speculate. Having seen the 19th century accusations against authors, lawyers, and public officials alike of being paid by the word, my best guess is that it’s a mix of modern audiences taking century-old tongue-in-cheek criticisms too literally, and half-truths about authors whose novels were originally serialized.

In short, the idea that he padded out Moby-Dick for a few extra dollars is simply untrue. Ultimately, questions about how authors are paid and what they’re paid for is, again, a matter best suited for debate societies like Melville’s Philo Logos. But for now, I submit a tweet by @rajandelman which I think distills that conversation in under 140 characters:

References

In addition to the hyperlinked sources, I relied on the following materials for this post:

The Writings of Herman Melville: The Piazza Tales and Other Prose Pieces, 1839-1860) (eds. Harrison Hayford, Alma A. MacDougall, G. Thomas Tanselle; Historical Note by Merton M. Sealts Jr.)

Becoming Dickens: The Invention of a Novelist (Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, 2011)

The Titans: A Three Generation Biography of the Dumas (Andre Maurois, 1966)

The Incredible Marquis, Alexandre Dumas (Herbert Gorman, 1929)

Thank you for your efforts.

I remember hearing that Dickens was paid by the word.