God keep me from ever completing anything. This whole book is but a draught—nay, but the draught of a draught. Oh, Time, Strength, Cash, and Patience!

If you noticed that I haven’t posted anything in a few weeks and found yourself fiending for another Melville mystery, that’s because a few technical difficulties stood in my way. I had one draft ready to go two Sundays ago, only waiting for the pièce de résistance, a commission from a freelancer that was still several cycles of revisions away. Instead, I decided to pivot to a backup I’d been writing on and off for several months only to find that Substack had managed to erase about 3,000 words from their web editor, setting me back god knows how many hours. Nothing else was even close to finished and, frankly, I was feeling a little discouraged.

Several weeks later I’m still waiting on that commissioned piece and still waiting on Substack to get back to me about potentially recovering my missing draft. But I decided to lean into these frustrations and offer something different today, a kind of epitaph to a few ideas which, for various reasons, just never worked out as fully realized posts. Think of it as a behind-the-scenes look at the extreme, often deranged lengths to which I go to answer inherently silly questions.

So let this six-inch entry be their stoneless grave — if only so I can finally delete these from my drafts folder.

Jack Putnam, Herman Melville Impersonator

Late last year, as I began to look into the missing Melville bust in Lower Manhattan, I came across a photo you might recall of a man named John “Jack” Putnam, an educator and historian whose role at the South Street Seaport Museum included giving lectures and leading tours in character as Herman Melville. Such an experience had never even crossed my mind.

As far as I can tell, Putnam, who died at the age of 82 in September 2018, was the world’s one and only Melville impersonator (aside from a few actors who have played him in movies), and it was a role he was destined to play.

Born and raised in Massachusetts, he first encountered Moby-Dick when it was read to him as a child who, like any good metaphysical philosopher, was becoming fixated on the sea. He majored in English at Harvard and took a course about Melville that seems to have shaped much of the rest of his life, as did the summer jobs in Nantucket where he met his wife. Meanwhile, he spent part of his time in the Navy Reserve Officer Training Corps and, after graduation in 1958, completed his service aboard aircraft carriers and submarines.

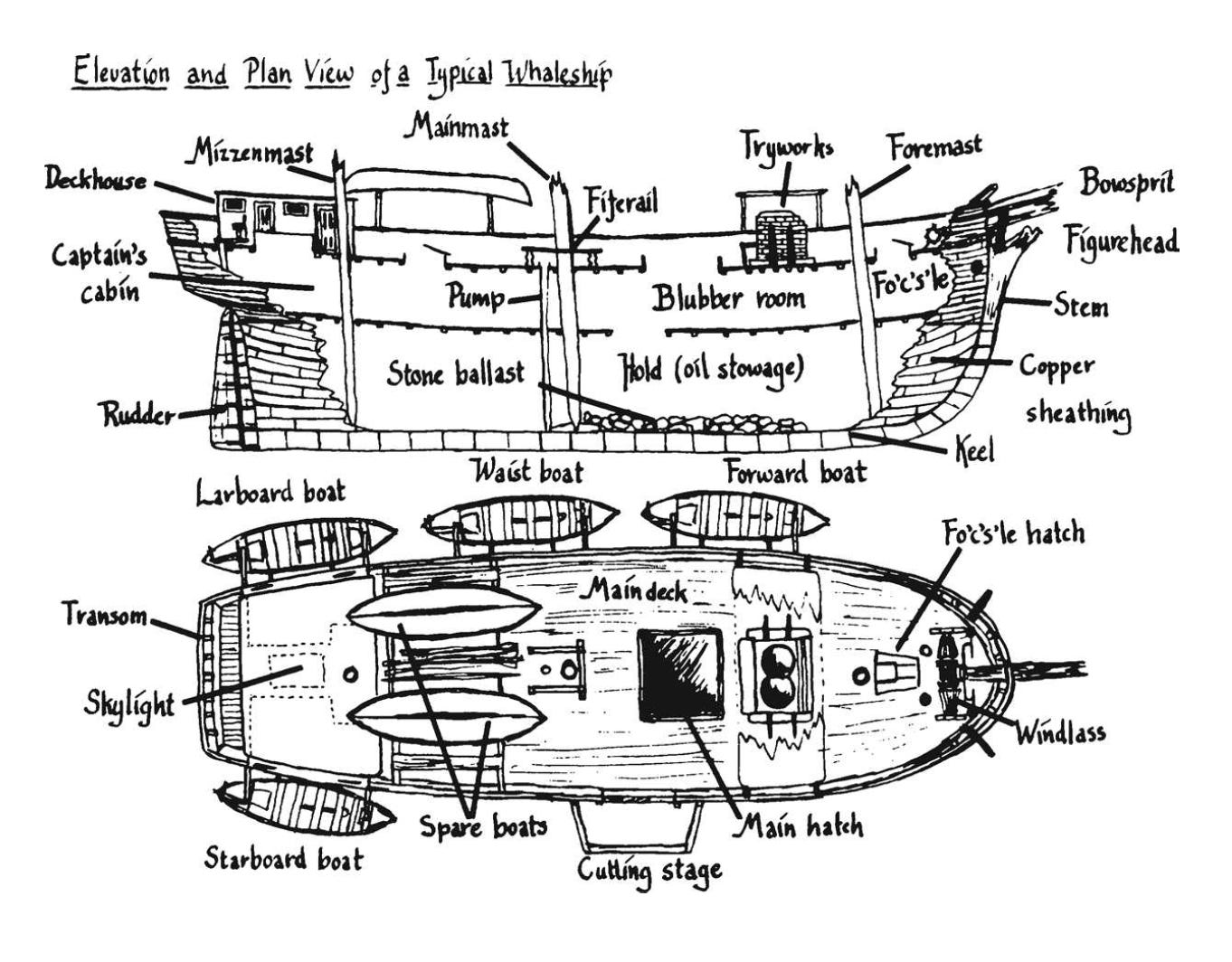

Putnam’s devotion to Melville continued into his professional life, embarking on a series of jobs around the country as an editor at various academic presses. It was during this time he helped compile the definitive Northwestern-Newberry texts of Melville’s complete works, and contributed an illustrated essay to the Norton Critical Edition of Moby-Dick titled "Whaling and Whalecraft: A Pictorial Account." The essay, which shows detailed plans of typical 19th whaling ships and boats, has been included in every subsequent edition of the volume.

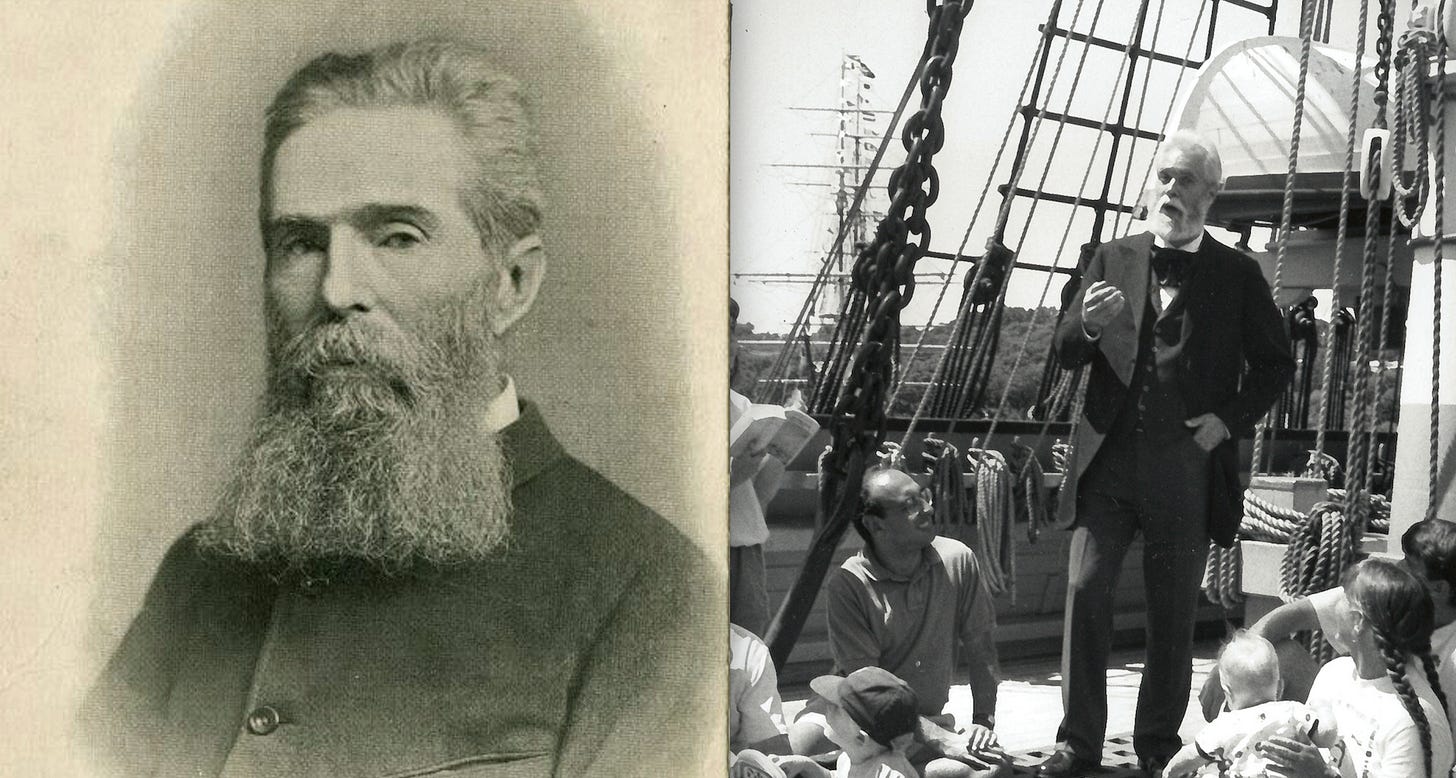

Putnam’s future as a Melville impersonator was beginning to take shape in the early 1980s when he began working at the South Street Seaport Museum, reciting portions of Moby-Dick for visitors. The novelty earned him an invitation to perform at Mystic Seaport’s still-nascent Moby-Dick marathon, rattling off Chapter 1: Loomings from memory but now decked in full 19th century garb. By his own admission, he bore "only a vague resemblance” to an older Melville. “After a certain age,” he stated humbly, “as a member of this gene pool, if you keep your hair and grow a beard you begin to resemble Herman.”

Personally, I thought he was a reasonably close match to the photo of Melville in his late 60s. Compare it to this photo of Putnam performing aboard the Charles W. Morgan at Mystic in 1993. (The beard had a little ways to go, to be fair).

For the next 25 years, Putnam was frequently called upon to perform at various Moby-Dick marathons and other Melville celebrations around the Northeast. He also created a one-man play as Melville, gave lectures in character, and even led a guided tour up Monument Mountain, recreating the author’s famous picnic with Nathaniel Hawthorne.

But these details of Putnam’s life as a sailor, a writer, an educator, and a performer are all widely available in articles about him through the years, as well as his obituaries in the New York Times, the Boston Globe, the Waterfront Alliance, and the Belmont Citizen-Herald. Merely summarizing from these sources with a few grainy photographs isn’t really what I like to do here.

Rather, the animating question I had was just as selfish as any of the investigations I take on: I wanted to see him perform as Herman Melville! Specificaly, the value I wanted to add here was finding video footage of his performances, whether from his one-man show, giving a lecture, or even just reciting passages from the book. How easy this would be, I (foolishly) thought.

There seemed to be nothing on YouTube, whether by name or from combing through clips of various Moby-Dick marathons through the years. I then started collecting every article I could find about Putnam from digital newspaper archives, most of them previews for upcoming performances at places like the Mystic Seaport Museum, South Street Seaport Museum, the Alice Austen House, the Staten Island Zoo, the Hudson River Waterfront Museum, and whaling museums in New Bedford, Nantucket, and Cold Spring Harbor, NY. One by one the archivists for these institutions got back to me to say that their searches came up empty.

I also reached out to several Melville scholars and the Melville Society’s Facebook group, assuming that at least a few people there would have attended a marathon there and whipped our their phones when the man of the hour (25 hours, to be exact) stepped behind the podium to kick off the event. Many folks expressed their interest in anything I turned up, but none had any video to share.

Having exhausted all other options, I found contact information for Putnam’s children and asked for their help. One of his daughters told me that, unfortunately, they too had nothing to share, but there was one place I might look. She recalled many years ago watching the episode about Moby-Dick from The Learning Channel’s Great Books series and being surprised to spot her father in a brief cameo. “My memory is a little fuzzy (it aired in 1996), but near the end, a man portraying Melville appears on screen with his back to the camera, locking the custom house door. Imagine our surprise when the man turns to face the camera--and there was Jack Putnam.”

I kicked myself for not thinking to check IMDb, but there he was alongside another credit as a historical consultant for a documentary about the sinking of The Essex. Naturally, nearly every episode of TLC’s Great Books is freely available on YouTube except for Moby-Dick. What else could I do, friends, but buy a VHS of the episode on eBay and digitize it at a nearby, tech-friendly library?

When the digital transfer finished and the VHS began automatically rewinding, I scrolled through the file and, toward the end, found Putnam in the customs house scene just as his daughter remembered. Even better, it was actually slightly longer than him just locking the door and turning to face the camera. So here, in all its grainy, gauzy, slightly-damaged glory, is a minute and a half of Jack Putnam-as-Melville, with narration by Donald Sutherland and a talking head interlude by author/”Moby Dick” screenwriter Ray Bradbury.

I can’t say I stand behind several statements made in the episode or even this short clip (contrary to popular misconception, Melville’s New York Times obituary spelled his name just fine, though it mangled “Mobie” Dick), but it’s the only 90 seconds of video of Putnam that I managed to find.

While it’s not a complete failure, this wasn’t particularly satisfying to my initial question. Jack appears only briefly and has no speaking lines. While it’s nice that they asked him to do it, it was a role which could have been played by just about any man with a white beard. I still feel certain that there’s footage out there on someone’s hard drive or even home video, but I figure I probably have a better chance of finding those people with this post than continuing my needle-in-a-haystack approach by reaching out to people one by one.

More importantly, the takeaway here is that there’s an opening for anyone with a good memory and passing resemblance to carry Jack Putnam’s torch as the world’s best and only Herman Melville impersonator. Now what was that first line again?

Herman Melville Square, Here and Gone (Again)

Back in November when I was looking into New Bedford’s three-day celebration of John Huston’s 1956 film adaptation of Moby-Dick, there was one off-shoot of an idea that was both solved too easily yet unresolvable in a more significant way. Let me explain.

As I wrote about, one part of the festivities involved Gregory Peck and New Bedford Mayor Francis Lawler dedicating a “Herman Melville Square” in the city, memorialized in this photo of Peck with the recently-crowned Miss New Bedford Carole Adams. A reporter for the Berkshire Eagle, you may recall, noted glumly that the dedication “was about the only time [Melville’s] name was mentioned during the whole three days.”

It wasn’t clear, though, where exactly the square was located, or whether it was still referred to as Herman Melville Square. A side-quest was born.

The first question was the easy part. Although I’m not really familiar with New Bedford, looking closely at the photo I was able to figure out that the photo was taken at the intersection of Williams and Pleasant streets looking west. One clue was that you can see the unmistakeable steeple of the First Baptist Church in the background. Another was that right behind Miss New Bedford’s hat you can see the top of the city’s famous “Whaleman” statue outside the New Bedford Free Public Library, installed in 1913. (The inscription below the seagulls reads, of course, “A DEAD WHALE OR A STOVE BOAT.”)

But when Peck and his posse left the city and the parade floats were returned to wherever parade floats live, the designation and that flimsy sign seem to have left with them; I could find no indication that anyone in New Bedford continued to refer to the intersection as Herman Melville Square. I could only assume that the ceremony had been just one more piece of the film’s PR campaign and that there had been no official proclamation from the mayor’s office.

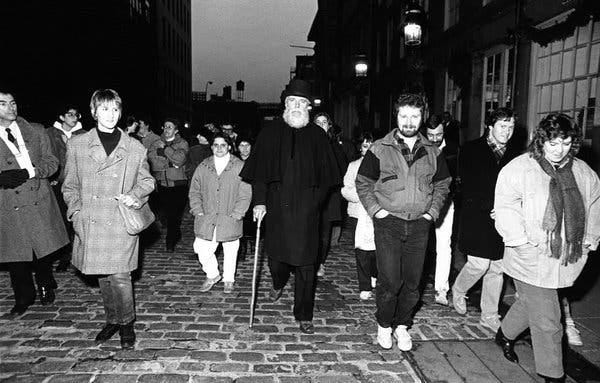

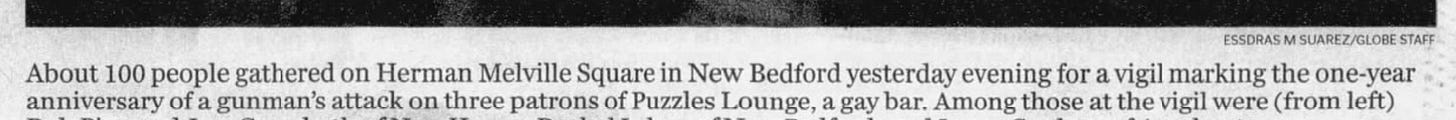

That is, until I came across an article in the Boston Globe from 2007, where the name was used, of all places, in the caption to a photo of a community vigil held after a neo-Nazi attacked three patrons at a local gay bar (thankfully, all survived). After that caption, it was crickets once again. What was happening here? Did a beat reporter wake up from a 50-year coma?

It was a real head scratcher until I read an article in the New Bedford Standard-Times about the city’s fiftieth anniversary celebration of the Moby Dick film premiere, recreating many of the events staged when Peck and Huston were in town. Mayor Scott Lang, the article said, “dedicated the area near the whaleman statue in front of the public library Herman Melville Square. A plaque marks the new designation.”

A plaque, you say? Now that sounds official. Was Mayor Lang trying to right a wrong? Once more into the fray I went, back trying to figure out whether or not this intersection was officially recognized as Herman Melville Square. It was not promising to discover that no one at City Hall — which, I should note, is located on that intersection — had any idea what I was talking about. The city clerk transferred me to the city council clerk, who transferred me to the mayor’s office, which recommended I call the city clerk. I declined the offer to be connected directly.

Instead, I got in touch with a librarian at the public library’s history room, who dug up Mayor Lawler’s 1956 Annual Report and found no mention of the dedication as an official municipal act, nor was it in the reports of relevant departments like parks, traffic, or public works. This appeared to confirm that the original dedication was simply a publicity stunt dreamed up by Warner Brothers.

But what about Mayor Lang’s dedication in 2006? Well, those records haven’t been transferred to the archives yet, and no one at City Hall seemed too eager to help me figure this out. My librarian friend, trying to let me down easily, suggested that it also was probably just for show. “But there was a plaque!” I insisted. Yes, it was no longer there just 18 years later, and No, I couldn’t find any photographic evidence of it, but I didn’t know how else to explain that photo caption.

The only person left to contact at this point was the man himself, former Mayor Scott Lang, who is now a practicing lawyer in New Bedford with an office half a mile from what will always and forever be, to me, Herman Melville Square. I scheduled an email to be sent out at 9AM and, amazingly, he responded 12 minutes later:

Thks for email I will get back to you. Scott.

I got back to him right away. Less amazing was that he never did get back to me, nor did he respond to several follow-up emails. I’m proudly a pest when it comes to research, but I do try my best not to harass anyone more than necessary. (That said, if you’re reading this Mr. Lang, please get in touch).

As a last ditch effort, I figured it wouldn’t hurt to send that ubiquitous city clerk one last email asking how a person might suggest to the city that they finally do make an official proclamation to rename the intersection in Melville’s honor. (Never mind that I’m not a resident and have only stepped foot in the city once in my life). That email, unsurprisingly, also went unanswered.

Sadly, New Bedford just wanted no piece of this and meanwhile I had a missing Melville bust to locate.

Writers gotta write. Thanks for this lighthearted view into your process. Even dead ends can be interesting.