EXTRACTS: The Family Jernegan

; or, on a storied whaling family from Martha's Vineyard

Last week I wrote about Amos P. Smalley, the Wampanoag harpooner who slew a giant white sperm whale in 1902 and lived to tell the tale.

Among the many rabbit holes I fell into while researching the story was something from Smalley’s Reader’s Digest piece about how wasn’t aware of Herman Melville’s white whale until 35 years after his own encounter.

But I didn't know there was a story about it until 35 years later when Marcus Jernegan, a professor of history and himself the son of a whaling captain, came up to my house at Gay Head and asked me about "Moby Dick." From him I heard the story that whalers used to tell some 50 years before my time of a white sperm whale that raged around the Pacific and was more ferocious than anything ever met on land or sea.

Always on the lookout for strange and interesting tangents, I thought it worthwhile to look into Marcus and the Jernegan family of Martha’s Vineyard to see if anything caught my eye. Little did I know I was knocking at the door of an esteemed family in whaling history, one with both an fascinating connection to Herman Melville and which also produced arguably the most unlikely whaler of the 19th century.

Here are quick glimpses at both of these stories.

Pt. 1: Captain William and the Stone Fleet

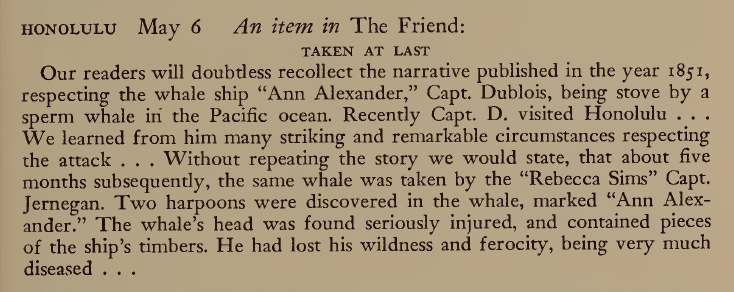

I admit that the surname Jernegan should have already been on my radar, appearing in a number of history books and articles as one of the first European families to settle on Martha’s Vineyard—rather like the Coffins, Starbucks, and Macys of Nantucket. A quick search of my digital Melville/whaling library returned more than a few hits, but foremost among them was an entry in Jay Leyda’s Melville Log dated May 6, 1954.

Though not directly part of Melville’s life, Leyda includes an excerpt from the Honolulu newspaper The Friend which follows up on the whaler Ann Alexander, rammed and sunk by a sperm whale just weeks before Moby-Dick was published. The wreck bore remarkable similarities to the book, with the exception that this crew survived when they were rescued two days later floating in their whaleboats.

Evert Duyckinck rushed to notify Melville of the Ann Alexander, to which he replied: “What a Commentator is this Ann Alexander whale,” imagining the leviathan as one of his literary critics. “I wonder if my evil art has raised this monster.”

Dear Duyckinck — Your letter received last night had a sort of stunning effect on me. For some days past being engaged in the woods with axe, wedge, & beetle, the Whale had almost completely slipped me for the time (& I was the merrier for it) when Crash! comes Moby Dick himself (as you justly say) & reminds me of what ! have been about for part of the last year or two. It is really & truly a surprising coincidence - to say the least. I make no doubt it is Moby Dick himself, for there is no account of his capture after the sad fate of the Pequod about fourteen years ago. — Ye Gods! What a Commentator is this Ann Alexander whale. What he has to say is short & pithy & very much to the point. I wonder if my evil art has raised this monster.

The follow-up item in the Honolulu Friend, published three years later, explains that six months after the Ann Alexander was sunk that same whale was killed by the Rebecca Sims. The whale was identified by the harpoons still stuck its side along with “pieces of the ship’s timbers.” The master of that ship was one Capt. William Jernegan.

(You can read the article in its entirety thanks to the Hawaiian Mission Houses Digital Collections.)

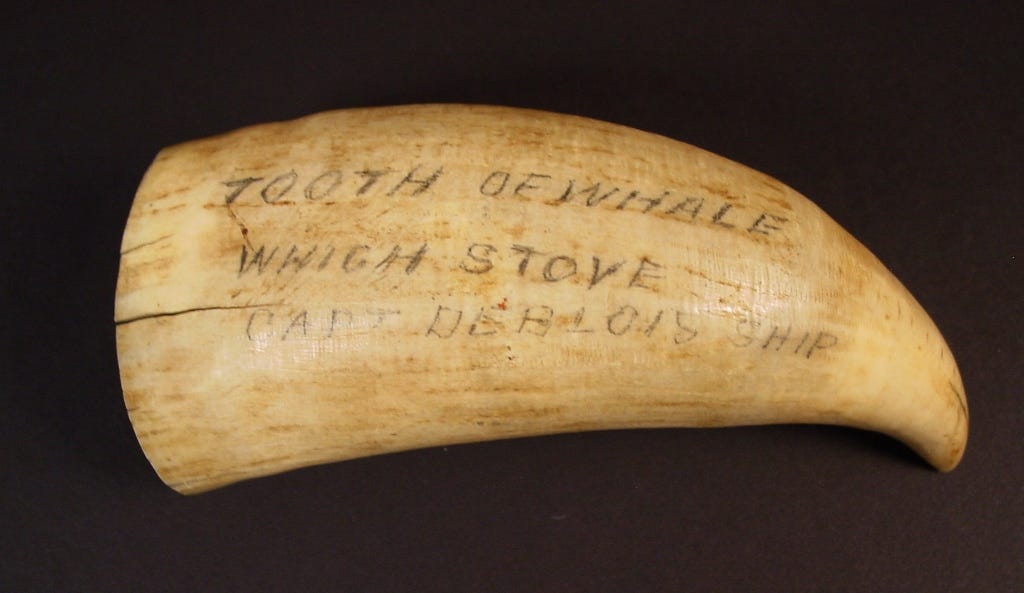

Jernegan even saved one of the whale’s teeth as a keepsake for the Ann Alexander’s Captain DeBlois, inscribing it succinctly: “TOOTH OF WHALE WHICH STOVE CAPT DEBLOIS SHIP.”

Sadly, it doesn’t appear that the logbook for the 1851-1852 voyage of the Rebecca Sims survived which might have documented the slaying and the amazing discovery of the harpoons. On the other hand, as we saw with the Platina and its white whale, maybe it wouldn’t even have warranted a passing remark beside the weather report.

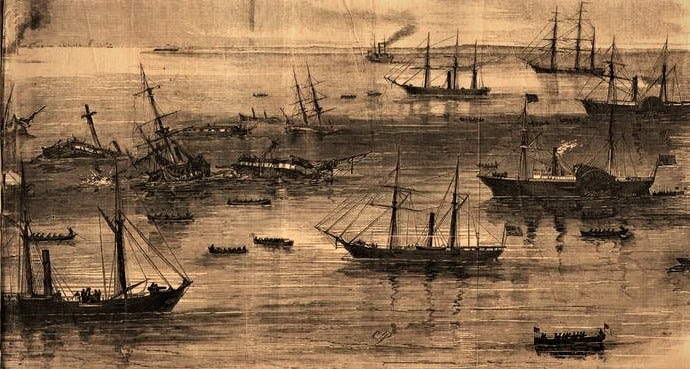

It’s also unknown whether Melville was made aware that the destroyer of the Ann Alexander was later caught and killed, but there is one last fascinating connection I couldn’t help but mention here. The Rebecca Sims, built in 1801, was originally used for general transatlantic trading and was only refitted as a whaler around 1850. But as it neared the end of its useful life in October 1861, the ship was acquired by the Union Navy, one of dozens of other aging whaling ships used as part of a strategy to thwart Confederate supply routes. They would be part of the so-called Stone Fleet, deliberately sunk in major ports and shipping channels with the aim of making them impassable.

Two months after its purchase, the Rebecca Sims and 15 other ships were sailed to Charleston harbor and sunk after being loaded with stone. A correspondent from the New York Herald who saw the aftermath wrote with obvious glee at the vengeful tactic:

[W]ith a fleet of ships sunk across and blockading an important channel, leading to what was once a thrifty city, but what is now the seat of rebellion, and an object of just revenge, the dismasting of the hulks, within sight of the rebel flag, and rebel guns, is really an unalloyed pleasure. One feels that at least one cursed rat-hole has been closed, and one avenue of supplies cut off by the hulks.

The plan, alas, was ultimately a failure. For one, it didn’t take long for the hulls to disappear fully into the water and/or break apart. The ships were also sunk far enough apart that the Confederate Navy were able to simply steer around them. Worst though, and obvious in hindsight, was that the Confederate Army concluded from the blockade that the Union must not be planning to attack Charleston, and quickly shifted valuable resources to prepare for assaults elsewhere.

But what of this Melville connection? Well, who else would mourn the needless destruction of old whaling ships but a nostalgic former whaler? In the days after the Rebecca Sims and the others were sunk, Melville sat down to write the poem “The Stone Fleet. An Old Sailor’s Lament,” later published as part Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War. Here it is in full:

I have a feeling for those ships,

Each worn and ancient one,

With great bluff bows, and broad in the beam:

Ay, it was unkindly done.

But so they serve the Obsolete—

Even so, Stone Fleet!

You'll say I'm doting; do but think

I scudded round the Horn in one—

The Tenedos, a glorious

Good old craft as ever run—

Sunk (how all unmeet!)

With the Old Stone Fleet.

An India ship of fame was she,

Spices and shawls and fans she bore;

A whaler when her wrinkles came—

Turned off! till, spent and poor,

Her bones were sold (escheat)!

Ah! Stone Fleet.

Four were erst patrician keels

(Names attest what families be),

The Kensington, and Richmond too,

Leonidas, and Lee:

But now they have their seat

With the Old Stone Fleet.

To scuttle them—a pirate deed—

Sack them, and dismast;

They sunk so slow, they died so hard,

But gurgling dropped at last.

Their ghosts in gales repeat

Woe's us, Stone Fleet!

And all for naught. The waters pass—

Currents will have their way;

Nature is nobody's ally; 'tis well;

The harbor is bettered—will stay.

A failure, and complete,

Was your Old Stone Fleet.

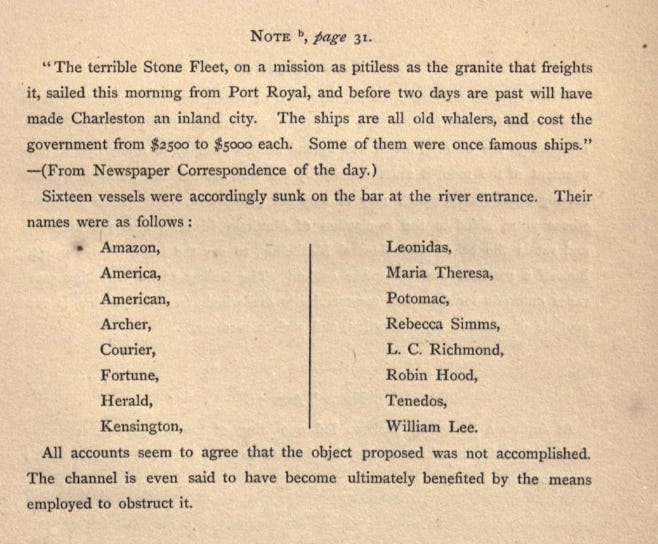

Melville wasn’t content to leave it there, even. Among several pages of notes at the end of Battle Pieces he excerpts an article about the Stone Fleet from the New York Tribune, copying over a list of the sixteen ships sunk at Charleston as if mourning fallen soldiers. Whether or not he knew it was the Rebecca Sims which had slain “Moby Dick himself”, he duly recorded its name so that all posterity would remember the “glorious” craft.

Pt. 2: Whalers Say the Darndest Things

The same year that the Rebecca Sims was sunk in Charleston, another Edgartown whaling captain named Captain Jared Jernegan was returning home after a three-year whaling voyage. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to figure out exactly how he was related to William Jernegan, though their lives, communities, and careers overlapped to a great extent. Let’s just call it ‘not-so-distant cousins’ but do let me know if anyone figures it out.

In any case, Captain Jared came home and although he was already 36 and had three children with a wife who died in childbirth, over the next decade he and his second wife Helen had three more children in between voyages: Laura in 1862, Prescott in 1866, and Marcus in 1872.

Marcus Jernegan, as we know, was the man who sought out Amos Smalley to talk about his white whale. But while he spent much of his life studying and teaching history at the University of Chicago, it wasn’t such a long journey to find the former harpooner on Martha’s Vineyard. He’d retired in 1937 and moved back to Edgartown, turning his attention to the history of the whaling industry. Over the next few years, he compiled extensive data on Vineyard whaling from logbooks and lectured on the subject until his death in 1949.

Prescott Jernegan, who had little interest in the family trade, instead became an ordained Baptist preacher who and made a name for himself by claiming he knew how to extract gold from seawater, a process which he said had been “revealed to him in a heavenly vision.” In the end, he and a partner bilked hundreds of thousands of dollars from investors and fled the country, never to be seen again.

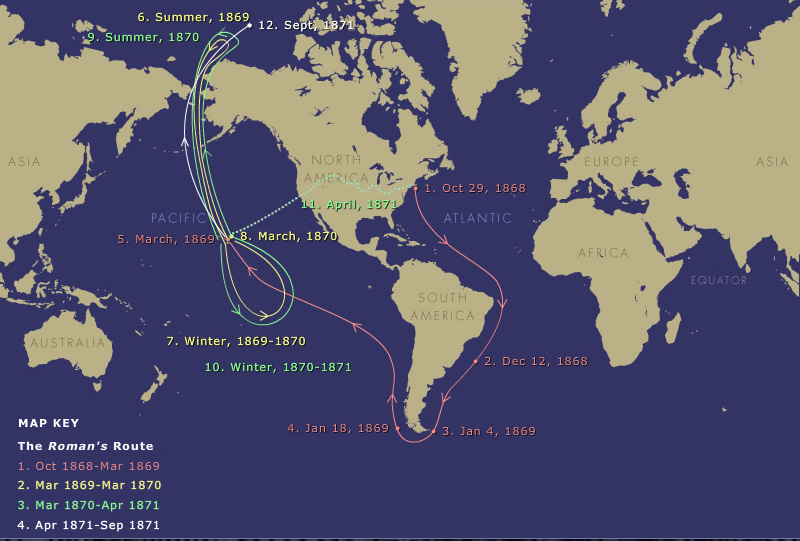

The most noteworthy of Jared and Helen’s children, however, was their eldest, Laura. Shortly after her birth in 1862, Captain Jernegan left his family behind to command the whaler Oriole and was away for the next three years. When it was time to return to sea in 1868, this time as captain of the whaler Roman, he decided he couldn’t leave Helen, Laura, and toddler Prescott behind.

Jernegan had the crew build a small room with a desk on the ship’s deck where Helen went over lessons with Laura, but for the next three years the fearless six-year-old became an astute observer of day-to-day life aboard a whaler, writing it all down in her diary. It is, to say the least, the most adorable whaling logbook you’re likely to come across.

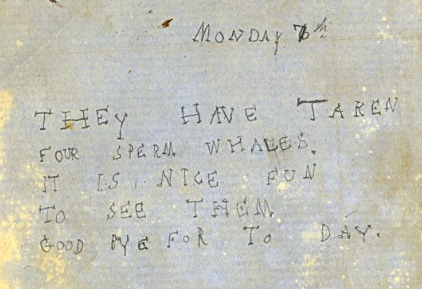

Captured in the diary are accounts of what she saw, watching the men processing whales, interactions with animals, fights with her brother, schooling, and just about anything else a child might think about aboard a ship, each ending with the polite “GOOD BYE FOR TODAY.” Take, for example, these early entries from December 1868 (age 6), completely unfazed by the butchery of whaling:

MONDAY 7th

THEY HAVE TAKEN FOUR SPERM WHALES. IT IS NICE FUN TO SEE THEM.

GOOD BYE FOR TO DAY

WEDNESDAY 9th

THE MEN ARE BOILING THE BLUBBER THAT MAKES THE OIL.

GOOD BYE FOR TO DAY

Laura wasn’t particularly sentimental about the other animals on board, either, including the ducks she saw on Tuesday and ate for dinner on Friday.

TUESDAY 15

THERE IS NO WIND TO DAY. THE MEN ARE STOWING THE OIL DOWN WE HAVE 4 DUCKS ON BOARD OF OUR SHIP. GOOD BY FOR TO DAY

FRIDAY 18

THE WIND BLOWS VERY HARD. WE HAD DUCKS FOR DINNER.

In January 1869, Laura (age 7) was rather nonchalant about seeing Cape Horn.

MONDAY 4th

WE PAST BY CAPE HORN TO DAY. IT IS A LARGE BLACK ROCK. SOME OF THE ROCKS LOOK LIKE A STEEPLE OF A CHURCH. GOOD BY FOR TODAY.

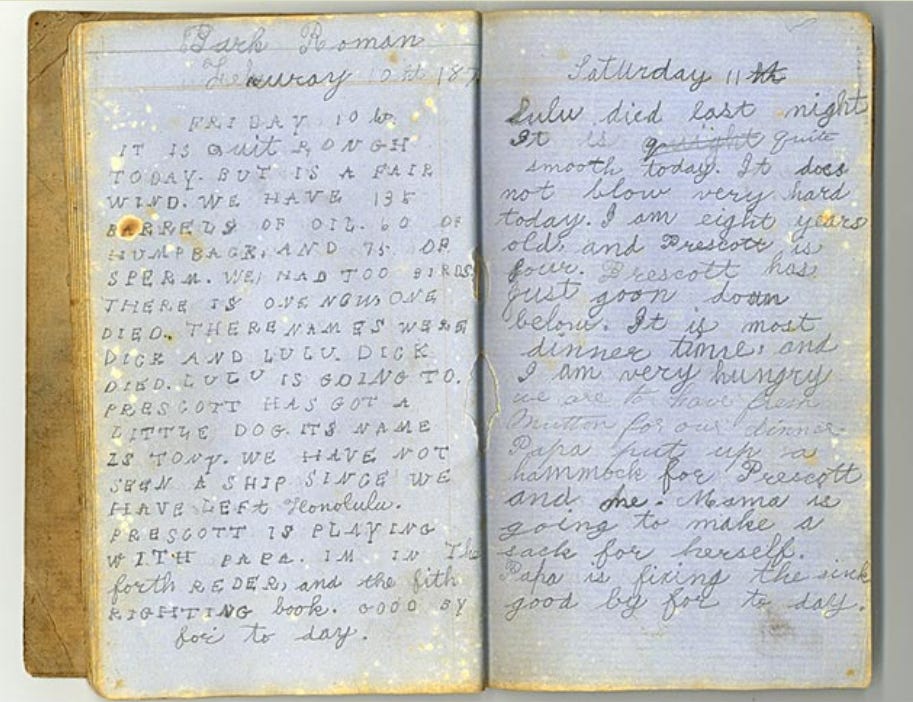

Perhaps no other entry portrays the chaotic mind of a child than the one from February 10, 1871, bouncing back and forth between whales, birds, dogs, death, family, and school within a few lines.

FRIDAY 10th

IT IS QUIT ROUGH TODAY. BUT Is A FAIR WIND. WE HAVE 135 BARRELS OF OIL, 60 OF HUMPBACK. AND 75 OF SPERM. WE HAD TOO BIRDS. THERE IS ONE NOW, ONE DIED. THERE NAMES WERE DICK AND LULU. DICK DIED. LULU IS GOING TO. PRESCOTT HAS A LITTLE DOG. ITS NAME IS TONY. WE HAVE NOT SEEN A SHIP SINCE WE HAVE LEFT HONOLULU. PRESCOTT IS PLAYING WITH PAPA. I AM IN THE FORTH REDER, AND THE FITH RIGHTING BOOK. GOOD BY FOR TO DAY.

While Ishmael might have taken several paragraphs to describe the idle, indolent days between hunts, Laura gets the point across in just a few words in what is easily my favorite of the entries:

TUESDAY 19

PAPA OPENED ONE OF THE COCONUTS IT IS SOFT INSIDE. PRESCOTT LOVES THEM. THARE IS A FLY ON MY FINGER. HE HAS FLEW OF NOW. Good By For to day.

Amazingly, at no point does she evince any fear, shock, or disgust at the work going on around her which, even in description, is a non-starter for many modern readers of Moby-Dick. Nor did her parents show any particular concern about shielding their children from what was going on around them. Helen later recalled watching her kids “climb up on the transom and amuse themselves by watching the sharks follow the ships… They were very large man eating sharks.”

The closest the family came to real danger was in March 1871 when the Roman anchored at one of the Marquesas Islands to pick up firewood and fresh water. When the captain denied the crew’s request to go ashore, more than a dozen drunken sailors mutinied and trapped the him and his family in the stateroom. The incident ended with 17 mutineers taking three whaleboats to shore, threatening to come back and burn the ship if they tried to leave. Jernegan fled anyway, making his way north to Honolulu. When they arrived, he sent his family back home to Edgartown before heading back to the Arctic with a new crew to catch more whales.

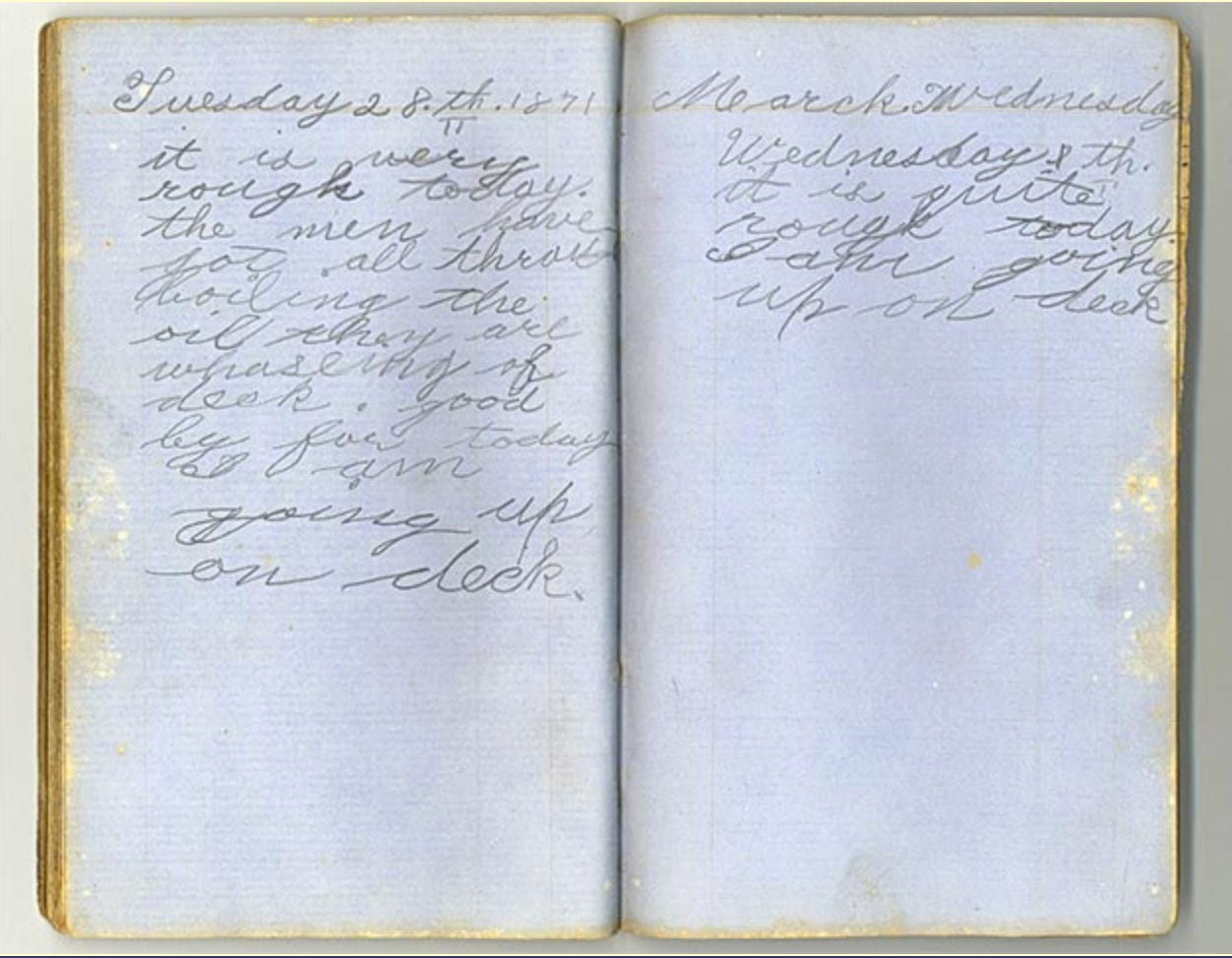

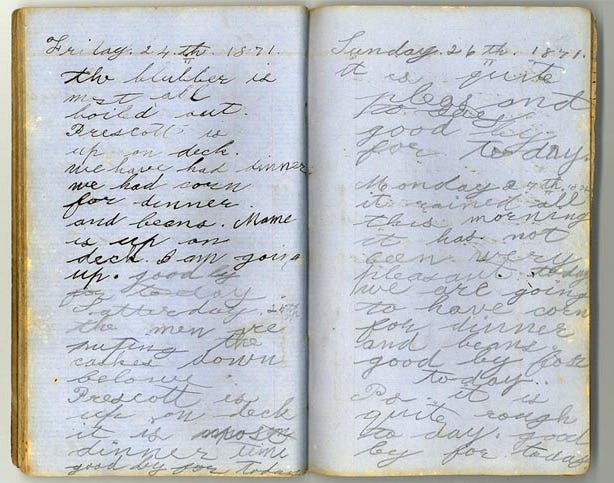

Surprisingly, Laura’s diary captured none of the excitement of the mutiny or even the trip back home, accomplished via steamship and a cross-country train trip. Her last entry was written in early March 1871, shortly before the mutiny, simply recording some bad weather in seasick cursive.

Wednesday 4th

it is quite rough today. I am going up on deck

Nearly sixty years later, Laura’s story was finally brought to light by her younger brother Marcus, published as a small volume in 1929. Since then, her story has been told and retold in various books, typically written for children. A complete scan of the book was made available by the Martha’s Vineyard Museum in 2010 on their “Girl on a Whaleship” website, along with a detailed history of the family and voyage assembled from Laura’s diary, her mother’s memoirs, and other documents. Across 43 pages you can almost watch Laura grow up simply in her handwriting from the first entry in December 1868, age 6:

To the last, in February 1871, soon turning 9:

That’s all I’ve got for you on the Jernegans. GOOD BY FOR TODAY!

References

Wilson Heflin, Herman Melville's Whaling Years (2004)

Jimmy Packham, “The Maritime Self on the American Whaleship,” in Shipboard Literary Cultures: Reading, Writing, and Performing at Sea (2021)

Wow, what great connections! I feel like the Stone Fleet – which I'd never heard of before – could be the subject of a fascinating novel, in addition to a poem.

And I love this bit from Melville's letter: " I make no doubt it is Moby Dick himself, for there is no account of his capture after the sad fate of the Pequod about fourteen years ago." Sequel bait! ;)

Excellent story. Thank you.