H is for Hakluyt

; or, how to spell "whale"

It seems only appropriate to start a new blog about Moby-Dick at the very beginning, with the novel’s famous first line. No, not “Call me Ishmael,” but with how the book truly begins:

ETYMOLOGY. (Supplied by a Late Consumptive Usher to a Grammar School.)

The pale Usher—threadbare in coat, heart, body, and brain; I see him now. He was ever dusting his old lexicons and grammars, with a queer handkerchief, mockingly embellished with all the gay flags of all the known nations of the world. He loved to dust his old grammars; it somehow mildly reminded him of his mortality.

At the outset of our adventure, Melville gives us a “pale Usher,” an archaic term for an assistant school headmaster with the sly double meaning of someone guiding us through the threshold of the two prologue chapters and into the novel.

We also perhaps glimpse Melville’s wistful image of himself, holed up in his study and working feverishly to complete yet another book to pay the bills. Hardly an old man in his early 30s, Melville nonetheless had long before hung up his oilskin whaler’s jacket and settled into domestic life first in New York and now Pittsfield, Massachusetts. He’s not “poor,” exactly, but constantly strapped for cash, borrowing money from anyone foolish enough to give it to him. His pale skin has long lost its tropical tanning earned when he was a younger man on the Acushnet whaler — a man who had once battled and dissected whales, jumped ship to live among native South Sea islanders, helped foment a mutiny for which he was briefly jailed, and hitched his way back to New York. He’s been reduced to daydreaming about the nations of the world, gazing at his dictionaries of foreign languages he once heard all around him. He thinks about his former life, time passing, entropy, dust and death. In fact, before we even meet the pale usher he’s already dead from consumption. In just three sentences, Melville tells us about himself, his surrogate narrator, and the great distance in time he feels from the life he led as a whaleman.

In one last Melvillian twist (if not one he could have anticipated), since his own ushering into the canon of Great American Novels in the 1920s, this strange vignette devilishly subverts the expectations of new readers who turn to the first page searching for an infamous opening line and instead find a sad, dead usher. Moby-Dick has been capsizing reader expectations since its publication in the 19th century and that continues today, whether in the realm of the moral, religious, narrative, or formal.

But what interested me enough for a thorough investigation is the next line in Etymology, a quote from someone named “Hackluyt.”

“While you take in hand to school others, and to teach them by what name a whale-fish is to be called in our tongue, leaving out, through ignorance, the letter H, which almost alone maketh up the signification of the word, you deliver that which is not true.” —Hackluyt

The usher is dead and buried and we’re presented with a mysterious, almost mystical suggestion that the silent H in whale is that which gives it meaning — plus an unusual scolding that to teach otherwise is to lie. New readers might be relieved that we’re at least talking about whales, but there’s little else to do but scratch our heads and wonder what this could mean or what significance it might have going forward. And what sort of deviant is teaching others to misspell the word whale?

The prominence of the Hackluyt quote is arguably even stranger considering that the second prologue chapter, Extracts, presents a deluge of “random allusions to whales… in any book whatsoever, sacred or profane.” In other words, Melville seems to have specifically selected this one quote from among nearly 100 others to be the first words we read having to do with whales. All others, whether from the Bible, Shakespeare, Milton, whalers, or scientists, come second in an unending torrent that most people understandably skim through. Hackluyt is special.

In fact, the first edition of Moby-Dick actually separated the pale usher vignette from the quote and the translations that follow, so that Hackluyt actually sat at the top of a new page, further indicating that Melville meant to stress its importance. (Most, if not all later editions have fit the entire chapter onto a single page.)

The first time I read Moby-Dick, I suppose I reacted as most people do: I glossed passed it and figured that Melville would eventually return to this idea (he doesn’t). The next few times we read it maybe we might try ourselves to imbue the H with some meaning; something to do with its haunting silence, the ghostly white whale, a quiet malevolence beneath the water. Or perhaps readers and scholars alike read it as just another of Melville’s many “higgledy-piggledy whale statements” – a curious statement about how to spell the word whale that Melville thought fit the “Etymology” brief.

Yet I’m drawn to the statement each time I begin anew, pausing on it each time I read the book as a meditative precursor to the maddened, perplexing storm of ideas ahead. I wanted to know more. What are we supposed to make of this idea? Was Hackluyt speaking literally? Why did Melville feature it so prominently at the start of the novel? Does the quote itself maketh up the signification of Moby-Dick?

The Letter H

Curiously, the editors of the various annotated editions of Moby-Dick have had little to say about the quotation or about Hackluyt. Only Luther S. Mansfield and Howard P. Vincent’s 1952 Hendricks House edition provided much information, noting that Melville is supposed to have found the quote in Charles Richardson’s A New Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1836. “Hackluyt,” they also note, is actually Richard Hakluyt (without the c), but it seems that Melville copied the quote and citation straight from Richardson’s dictionary, copying the error.

We also learn from Mansfield and Vincent that the passage comes from Hakluyt’s book, The Principal Navigations (1598), citing further “Vol 1., p. 568-Argrimus Ionas of Island, Part 1, sec. 14.” And lastly, they also intriguingly refer to Hakluyt as the “compiler,” and not the author. But more on all of this later.

I wanted to start with the entry in Richardson’s dictionary, and thanks to the HathiTrust Digital Library, we can actually see the entry for ourselves:

Like Melville, Richardson provided several translations, including the “A.S.” (Anglo-Saxon), German, Swedish, and Greek, and a brief etymological connection to the Anglo-Saxon Walw-ian, “to roll, to wallow” which Melville quotes just a few lines later after Hakluyt.

[While we’re on the subject, an online Anglo-Saxon dictionary gives “hwæl” for whale instead of whœl, and “wealwian” for “to wallow, roll,” which doesn’t appear to have any connection to whales. One source suggests that Richardson collected quotes for each word “to justify the preposterous theory of John Horne Tooke that each word had a single immutable meaning,” adding that Richardson’s “etymologies were as preposterous as his theories.” So there’s perhaps good reason to take this connection less than literally.]

After the quote about Jonah, we find the Hakluyt excerpt, though there are several differences. For one, Melville modernized the language in Moby-Dick, changing the U to V, changing schoole to school, and so on. The quote is also attributed to Hakluyt’s “Voyages,” as opposed to the Hendrick’s House citation of “Passages,” though both give the impression of being shortened from a longer title.

More interestingly, though, we discover that Melville also seems to have cut off the last part of the quote that Richardson provided, which reads:

"For val in our language signifieth not a whale, but chusing or choice of the verbe Eg-vel, that is to say, I chose, or I make a choice"

In other words, Hackluyt is saying don’t forget the letter H because in “our language” hval means whale, while val means choice. It’s not clear what the context is for this instruction, or even what “our language” means with respect to these strange words, but suddenly it seems less like mysticism and more like a banal grammatical note.

If Melville saw this passage in Richardson’s dictionary in full, clearly he would have understood its more prosaic meaning. He is the one who just invented and killed off a grammar teacher literally one sentence ago. Even more questions arose: did Melville choose to crop off the last sentence just because he liked how it sounded without? What did Melville want us to infer from the quote given that its intentionally misrepresented? Did Melville read Hakluyt’s book, and who was Hakluyt, anyway?

Richard the Anthologist

Richard Hakluyt (1553-1616), I learned, was an English writer, translator, and priest. Wikipedia also tells us that he held high positions in the courts of Queen Elizabeth I and King James I, and is best known for promoting the English exploration and colonization of North America.

Between 1583 and 1588 he was chaplain and secretary to Sir Edward Stafford, English ambassador at the French court. An ordained priest, Hakluyt held important positions at Bristol Cathedral and Westminster Abbey and was personal chaplain to Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, principal Secretary of State to Elizabeth I and James I. He was the chief promoter of a petition to James I for letters patent to colonize Virginia, which were granted to the London Company and Plymouth Company (referred to collectively as the Virginia Company) in 1606.

Although Hakluyt was not an explorer himself, he was “fascinated from his earliest years by stories of strange lands and voyages of exploration” and in his life became an “indefatigable editor and translator of geographical accounts.” Between 1589 and 1600 he published several editions of his multi-volume The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques, and Discoveries of the English Nation, collecting various transcriptions of the personal accounts of English explorers, maps and charts, and histories of attacks against England’s rival nations and histories of famous battles. This is why Mansfield and Vincent refer to Hakluyt as a compiler; his contribution came more in the act of anthologizing and translating accounts from explorers, scientists, historians, and so on.

Hakluyt and the Whales

The Principal Navigations also isn’t primarily a scientific or naturalist text, despite his now-most-famous mark on history coming in the form of a whale. But whales are mentioned with some frequency throughout the various accounts in the book. There are descriptions of various kinds of whales, accounts of passing by large pods of whales on the open ocean, whaling exploits, and even a translation of the word whale in Iroquois as “ainne honne,” as spoken in the village of Hochelaga (in present-day Montreal).

One of the many stories involving whales collected by Hakluyt involves a tall tale that whales off the coast of Iceland are so large taht mariners have mistakenly beached themselves on their back — just the kind of legend that we can imagine Melville would have loved to include (and excoriate) in Moby-Dick.

There be seen sometimes neere vnto Island huge Whales like vnto mountains, which ouerturne ships, vnlesse they be terrified away with the sound of trumpets, or beguiled with round and emptie vessels, which they delight to tosse vp and downe. It sometimes falleth out that Mariners thinking these Whales to be Ilands, and casting out ankers vpon their backs, are often in danger of drowning. They are called in their tongue Trollwal Tuffelwalen, that is to say, the deuilish Whale.

Returning to investigation, though, Richardson (like Mansfield and Vincent) helpfully notes that the Hakluyt quote we’re after is found in Volume 1 of 14, which contains 109 separate narratives concerning English voyages to the North and North East. Among them are an account of King Arthur’s expedition to Norway in 517, Francis Drake’s attack on Cadiz under Queen Elizabeth I (the so-called “Singeing the King of Spain's Beard”), an account of the Knights of Jerusalem, and John Cabot’s voyages to the Americas.

Digging into Volume 1 of The Principal Navigation, our first order of business is to figure out what piece of writing it appears in and who actually wrote it.

Arngrímur Jónsson v. Sebastian Münster

Luckily, Project Gutenberg has transcribed all 14 volumes of The Principal Navigation, so we can find the “letter H” quote quite easily, located just a few paragraphs below that one concerning those giant Trollwal Tuffelwalen always fooling the Icelandic people. In fact, they’re part of the same essay: a treatise by Icelandic scholar Arngrímur Jónsson titled “A Brief Commentary on Iceland,” published just a few years earlier in 1593. (If this name rings any bells, it’s because this is the same “Arngrimus Ionas of Island” cited in the Hendricks House annotations. Things were starting to make a bit of sense.)

Arngrímur’s treatise provided an early defense of Icelandic nationality and cultural history, part of a long tradition of “ethnographic insult and counterinsult by which European countries came to distinguish themselves in print.”

This defense of Iceland and subsequent works were important for introducing European scholars to the ancient literature of Iceland and the richness of the manuscripts present there. In the context of the mounting conflicts between Denmark and Sweden, which saw both countries trying to establish historical precedents for their empire-building, it also played a formative role in the development of European nationalism, participating in the ethnographic insult and counterinsult by which European countries came to distinguish themselves in print.

Arngrímur became an important figure in Icelandic nationalism as a result of the “Brief Commentary on Iceland” and his subsequent work, Crymogæa, a history of Iceland published in 1609 — so much so that in the mid-20th century the Icelandic government honored him by using a portrait on the 10 kroner note.

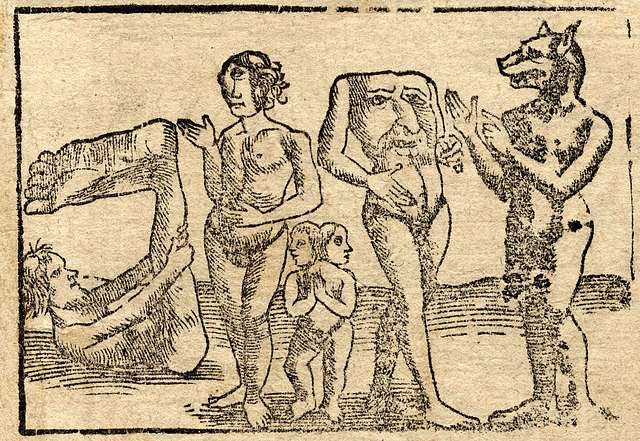

And yet, we have yet another layer: the story about those giant “devilish whales” still isn’t Arngrímur’s, but is rather an excerpt from another book, this one by German cartographer and cosmologist Sebastian Münster. In 1544, Münster had published his Cosmographia, “an immensely influential book that attempted to describe the entire world across all of human history and analyse its constituent elements of geography, history, ethnography, zoology and botany.” It’s also full of amazing drawings you may even be familiar with, such as this one of “blemmyes,” mythical headless men with their faces on their chest. And also that wolf guy and another man with a giant foot.

Cosmographia was one of the most successful and popular books of the 16th century, reprinted dozens of times in German, Latin, French, Italian, and Czech by the time that Arngrímur published his book in 1593. Not to be outdone, Münster was also featured on a German 100 Deutsche mark in 1980.

In any case, Arngrímur excerpted from Münster’s book, including the bit about the Trollwal Tuffelwalen, only in order to assail him for his many inaccuracies and lies. Arngrímur takes particular issue with the giant whales, calling it a “fable… bred of an old, ridiculous and vaine tale.”

The backs of Whales which they thinke to be Ilands. This fable, like all the rest, was bred of an old, ridiculous and vaine tale, the credite and trueth whereof is not woorth a strawe…. O silly Mariners that in digging can not discern Whales flesh from lumps of earth, nor know the slippery skin of a Whale from the vpper part of the ground: with out doubt they are woorthy to haue Munster for a Pilot.

If you’re getting hints of Melville’s tirades against the inaccurate beliefs about whales and whalers, you aren’t alone.

But Arngrímur saves the fieriest part of his tirade for Münster’s poor knowledge of the Icelandic language and grammar, specifically for translating “devilish whale” as Trollwal. Arngrímur tells him, in effect, to leave his beloved Icelandic out of his mouth, and here is where we find the quote.

But they are called in their language Trollwal. Go not farther then your skil, Munster, for I take it you cannot skill of our tongue: and therefore it may be a shame for a learned man to teach others that which he knoweth not himselfe: for such an attempt is subiect to manifold errours, as we will shew by this your example. For while you take in hand to schoole others, & to teach them by what name a Whale-fish is to be called in our tongue, leauing out through ignorance the letter H, which almost alone maketh vp the signification of the worde, you deliuer that which is not true: for val in our language signifieth not a Whale, but chusing or choise of the verbe Eg vel, that is to say, I chuse, or I make choise, from whence val is deriued, &c. But a Whale is called Hualur with vs, & therefore you ought to haue written Trollhualur. Neither doeth Troll signifie the deuill, as you interprete it, but certaine Giants that liue in mountaines. You see therefore (and no maruel) how you erre in the whole word. It is no great iniurie to our language being in one word onely: because (doubtlesse) you knew not more then one.

There’s a lot to take in here. First, not only did Münster forget the h in hval (note: the w→v seems to be a relic of translation), he chose the wrong word altogether for devil; troll doesn’t mean devil, you buffoon, it refers to the giants that live in the mountains. Go not farther than your skill, Münster. (Keep in mind, by the way, that Münster had been dead for 40 years by the time Arngrímur was writing this.)

Again, Arngrímur writes in a way that should feel uncannily reminiscent to anyone familiar with Moby-Dick. Throughout a significant chunk of the middle section of the book, Melville similarly tears apart scientists who circulate myths about whales, and the incompetent artists who drew them badly. Compare the above to the way that Melville/Ishmael roasts Frederick Cuvier’s drawing of a sperm whale (which, to be fair, is ridiculous):

But the placing of the cap-sheaf to all this blundering business was reserved for the scientific Frederick Cuvier, brother to the famous Baron. In 1836, he published a Natural History of Whales, in which he gives what he calls a picture of the Sperm Whale. Before showing that picture to any Nantucketer, you had best provide for your summary retreat from Nantucket. In a word, Frederick Cuvier’s Sperm Whale is not a Sperm Whale, but a squash.

Having learned all this, there’s one last critical piece of information about this “letter H” quote, which in some ways delivers us straight back to the heart of the mystical, mysterious sense in which Melville deployed it. Arngrímur didn’t write the Brief Commentary in English, he wrote it in Latin. In fact, Hakluyt included both the Latin and the English in The Principal Voyages, alternating between the two section by section. Here is the actual quote as written by Arngrímur, beside the English version:

ENGLISH: For while you take in hand to schoole others, & to teach them by what name a Whale-fish is to be called in our tongue, leauing out through ignorance the letter H, which almost alone maketh vp the signification of the worde, you deliuer that which is not true

LATIN: Dum enim vis alijs autor esse, quomodo nostra lingua balenæ vel cete appellentur, detracta, per inscitiam, aspiratione, quæ pene sola vocis significationem facit, quod minimè verum est, affers

I won’t pretend to know any Latin whatsoever, but for our purposes the relevant word here is aspiratione, or aspiration, in the sense of “articulation accompanied by an audible puff of breath.” The kind of puff of breath with which you would start the word hval in Icelandic.

In sum, Münster told the world in Cosmographia, in German, that in Iceland you’ll find giant “devilish whales,” which the Icelandic people call Trollval. Arngrímur angrily responded, if a tad bit late, that the word for whale isn’t val but hval — he’s missing the “aspiration” before the word. Hakluyt put the whole thing in his book and translated this critical word into English simply as: “the letter H.”

Thus, long before Melville pilfers the quote, understand that what we have is Arngrímur writing in Latin about Münster who wrote in German about Icelandic, all of which was translated by Hakluyt into English. It’s no wonder the pale usher had to dust off his old lexicons and grammars.

Moby-Dick

Two hundred years later, Melville opened Moby-Dick by quoting this brutal assault on a long dead German cartographer. It’s unclear (to me, anyway) whether Melville would or even could have known any of this context, i.e., whether he even would have had access to Hakluyt’s full Voyages book if he wanted to investigate.

But this actually isn’t the only time he mentions Hakluyt in Moby-Dick. In Chapter 56: Of the Less Erroneous Pictures of Whales…, Hakluyt is mentioned among Pliny, Cuvier, and others as having spread “monstrous” stories about whales. No particulars of Hakluyt’s crimes are provided, though. Could this be a reference to the Trollwal?

And in Chapter 75: The Right Whale’s Head—Contrasted View, Melville references Hakluyt a third time regarding baleen, and seems to understand that Hakluyt was merely the compiler, not the author.

In old times, there seem to have prevailed the most curious fancies concerning these blinds. One voyager in Purchas calls them the wondrous “whiskers” inside of the whale’s mouth;* another, “hogs’ bristles”; a third old gentleman in Hackluyt uses the following elegant language: “There are about two hundred and fifty fins growing on each side of his upper chop, which arch over his tongue on each side of his mouth.”

Melville’s use of the Hakluyt quote that happens to be in Richardson’s dictionary suggests that he was, indeed, merely copying from this source. Still, after all of this research I have unanswered questions about what Melville knew about Hakluyt’s work, and whether he might have seen a copy. Melville's Marginalia Online, a virtual archive of books that Melville was known to have owned and/or borrowed, has no record of Hakluyt in his possession, though possibly there was information about Hakluyt and the one-sided exchange between Arngrímur and Münster included in another work.

It’s another question entirely why Richardson chose this exact passage from Hakluyt to use in his dictionary as an example of the word “whale,” but as they say: not my whale, not my problem.

Trollwal 2: Revenge of Arngrímur

We might expect that Melville, undoubtedly chastened by Arngrímur’s excoriation of Münster, would have made doubly sure to provide the correct Icelandic translation as “hvalur” among the list of 13 languages below the Hakluyt quote – right? Ironically, and hilariously, no. An archive of the original American edition shows an even stranger error. The Icelandic translation is given not as WAL, VAL, or even HVAL, but simply as “WHALE.”

Melville should have been glad that Arngrímur had then been dead for 200 years.

The editors of the Northwestern-Newbury edition of Moby-Dick, who attempted to sort out all of the errors in transcription, typesetting, and translation in the original publications, speculated that Melville might have mistakenly believed the Icelandic word was “whale” — but that more likely it was simply an error by the typesetter.

The A[merican] and E[nglish] reading “WHALE,” which is not a possible Icelandic form, perhaps results from a slip by the A[merican] compositor, whose eye may have skipped to the next line of his copy, where “WHALE” properly appears. Conceivably Melville did think that “whale” was Icelandic, because the form “illwhale” appears on the same page (p. 130) of Uno von Troil’s Letters on Iceland (London, 1780) as the passage quoted in the “Extracts”– though this erroneous form was altered to “Illhwele” in the second (1780) and third (1783) editions of Troil, one of which Melville might have used instead of the first edition. There is no way to conjecture what form appeared in Melville’s manuscript, but it seems unlikely that the form was “WHALE” (Melville apparently wished, after all, to represent a variety of words in this list). Under the circumstances, the best course seems to be to emend the modern Iceland word “hvalur”.

That which “almost alone maketh up the signification”

As for what Melville thought the quote meant, or what he meant by using an altered version of it, we can only speculate. Several Melville scholars have offered their own poetic interpretations, linking the breathy sound of the letter H to the whale’s spout and ability to dive deep underwater. Caleb Crain, for example, pondered the letter’s “sound of breath” and compares it to a whale’s spirit, pondering what it means for a whale fight its mechanical urge to breathe.

The letter H gives the sound of breath—that is, of spirit—and whether a whale can go without breath is a crucial question about him. The whale is a fish that breathes air, “a spouting fish,” in Ishmael’s definition, but the whale is also able to dive and “live without breathing” for a time. If breath is understood as a mechanical process, then diving is spiritual; if breath is understood as spirit, then diving is a descent into pure mechanism. At the bottom of Melville’s metaphors lies, therefore, an “unemendable discrepancy,” to borrow a term from textual editor Harrison Hayford. Are whales remarkable for their spirit, or remarkable in being able to go without it?

Athanasius C. Christodoulou likewise suggests that the “secret” of Moby-Dick is “in its unseen ‘lung,’ the letter H, which breathes in the depths of its word/body.”

Citing Hackluyt’s extract, Melville warns us indirectly that the secret of his book is hidden not in the word “whale,” which spouts on the surface of the book’s pages (and is an optical illusion), but in its unseen “lung,” the letter H, which breathes in the depths of its word/body, and which only can exhale all vivifying air from inside. […]

Open-minded Melville, browsing Richardson’s dictionary, chose the first phrase of the extract from Hackluyt because the traveller’s remarks about the value of the characteristic letter H in the formation of the meaning of the word “whale” could be used to imply analogically the value of the vivifying mind or its concept in the formation of any word. Like the monogrammatic vocal sound H, which, although it is full of the air of our lungs and gives hypostasis and meaning to the word “whale” by its exhalation, is not heard in its pronunciation, the unseen mind (or its concept), hidden behind any word, though it comprises its true root, is not perceptible in its formation. If we stay on the visible surface and cannot dive into this invisible root, we will never speak the truth about human beings and life. All truth is hidden in this soundless and insensible H.

Though I think both writers beautifully capture elements of Melville’s enigmatic, inscrutable novel, I suspect neither investigated the context of Hakluyt’s quote and thus miss at least it’s literal meaning. Arngrímur (not Hakluyt) commands us not to omit the letter H in spite of its silence in the English word for whale, but because its breathy pronunciation is essential to its meaning in his own language.

To my knowledge (though please correct me if I’m wrong), this background has never been provided in annotations to an edition of Moby-Dick, nor have I seen it in any scholarly writing about the book. Certainly, the ease by which these fully-searchable texts can now be found online has made the once near-impossible task surprisingly easy. However, Crain and Christodoulou are among the very few that I’ve found who have taken the Hakluyt quote seriously enough to even opine on its meaning.

It could also be argued that because Melville took the quote at face value, so should we. Although to a certain extent I agree, and enjoyed Crain and Christodoulou’s takes if based solely on what was in front of them, it’s worth recalling that Melville didn’t simply take Hakluyt’s quote and reproduce it in full. He knowingly omitted the last sentence as it was printed in Richardson’s dictionary, concerning the Icelandic words val (choice) and eg-vel (I choose), thereby obfuscating its meaning and serving his own veiled purpose.

Separate from how scholars understand the quote as deployed in Etymology and the book as a whole, the uncanny echoes that reverberate from Münster’s encyclopedic (if ingenuous) mapping of the cosmos; Arngrímur’s proud but haughty defense of his values and culture; and Hakluyt’s compilation of mountains of information and stories shed enormous light on Melville’s character as a brilliant, independent, and sometimes arrogant iconoclast and adventurer. The research into a single letter in Moby-Dick has revealed fascinating intellectual ancestors hidden in plain sight like nesting dolls, right there on the first page of the book.

(Think that’s all there is to be said about a single letter in the Etymology chapter? Wait til you hear what Melville did to the Hebrew translation of whale. For another post!)

Great post! Almost a year late here, but Melville could have read Hakluyt at the New York Society Library, where he was a member in 1848 and 1850. The 1850 NYSL catalogue lists two copies of Hakluyt, from 1599 and 1809 (though I don't think they still have them in their collection).

Excellent inauguration of this blog - looking forward to more! I came here via the Berkshire County Historical Society, which preserves Melville's Arrowhead. And I'm delighted that you consulted the Project Gutenberg e-book of Hakluyt's magnum opus. I was one of the many volunteers who helped prepare it (via Distributed Proofreaders). We love it when our work is useful to others!