Moby Dick (i.e., the whale) is undeniably one of the most iconic characters in American literature, as immediately recognizable in New Yorker cartoons as he is as a paperweight, in restaurant logos, or even as a white blob in abstract art. The likeness doesn’t even need to be the right kind of whale to evoke in an instant the book, its cultural heft, and all that the whale is thought to represent as the target of Ahab’s murderous rage. In the end, the immortal, ubiquitous white whale prevailed over Ahab not only in the novel but in enduring symbolic resonance.

But it’s also undeniable that the whale’s blinding whiteness has obscured all of the other characteristics used to describe him throughout the book. Whether in the idealized forms of Rockwell Kent, the realistic illustrations of Anton Otto Fischer, or the grotesques of Gilbert Wilson, the white whale is always just that: a plain white sperm whale without any of the other physical markers noted throughout the book. Some of these details I’ve never seen in illustrations. With respect to all of the artists who have drawn Moby Dick, the truth is that none have paid particularly close attention to the many traits which are said to distinguish him from other sperm whales beyond his unusual coloring.

Despite hundreds of illustrated editions of the book, TV and film adaptations, cartoons, sculptures, scrimshaw, card games, and breakfast cereals (ok not breakfast cereals but what if…?), could it really be that Moby Dick is still “unpainted to the last,” nearly two hundred years later?

As Ishmael writes, “It is time to set the world right in this matter, by proving such pictures of the whale all wrong.” To this end, first I gathered every physical description of Moby Dick in the book and put them into the categories below, using photos of real whales and a bit of cetology. As fantastical as Moby Dick is in the superstitious minds of the crew, Melville’s descriptions are actually very much grounded in reality, backed up by science and observation.

And then, if only because someone had to do it, I hired an illustrator to put all the pieces together and show us the white whale at last.

1. A crooked, “scrolled” jaw

The trait that stood out to me as being the most overlooked by illustrators is that Moby Dick is said to have a “scrolled” and “crooked” jaw. To be honest, it wasn’t until my third or fourth read that I realized I didn’t have a clear idea of what this looked like in terms of whale biology. It had never been part of any drawing, nor do any of the annotated editions of the book provide a footnote about what a “scrolled” jaw is.

It’s not as if this deformity is marooned in the open waters of the middle section of the book, either. In fact, I’d argue it’s pretty significant! Moby Dick didn’t smash Ahab’s leg off with his tail, or crush it with the vast bulk of his body, nor was he involved in some rope-related dismemberment; it was torn off in the whale’s jaw. It’s kind of the main thing Ahab obsesses about. It was “the very jaws he hated.”

The crooked jaw is mentioned, for instance, in a key moment of Ahab’s quarter-deck speech and is specifically what jogs the harpooners’ memories of Moby Dick — more so than even its whiteness.

“Whosoever of ye raises me a white-headed whale with a wrinkled brow and a crooked jaw… […] he shall have this gold ounce, my boys!” […]

All this while Tashtego, Daggoo, and Queequeg had looked on with even more intense interest and surprise than the rest, and at the mention of the wrinkled brow and crooked jaw they had started as if each was separately touched by some specific recollection.

In Chapter 41: Moby Dick, we’re told that it was the whale’s “sickle-shaped lower jaw” which “reaped away Ahab’s leg, as a mower a blade of grass in the field.” And in one of Ahab’s last encounters with the whale, its “long, narrow, scrolled lower jaw” is again central to the action. Ahab grabs onto the jaw “curled high up into the open air” just before it snaps his boat in half.

It’s not surprising, then, that during his research for the book Melville made a small notation in his copy of Thomas Beale’s The Natural History of the Sperm Whale, leaving a mark on a paragraph about crooked jaws being bent to one side and “rolled as it were like a scroll.” (Note the small circle to the left)

So what does this look like? Well, it can actually take on one of many different shapes, “crooked” and “scrolled” being among the many variations of the deformity which is seen in about one in every 2,000 whales.

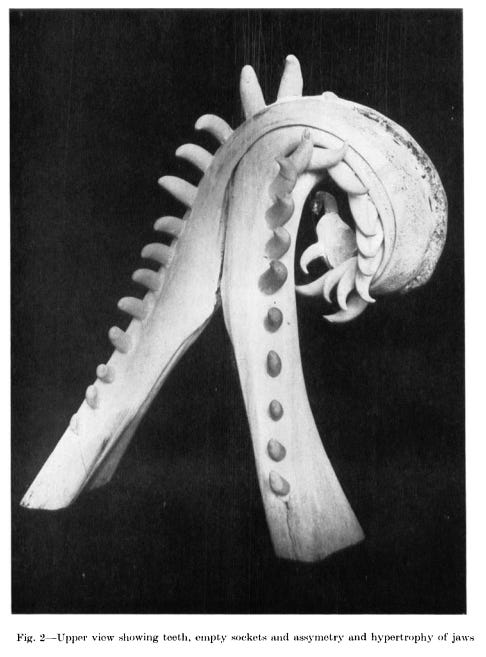

In short, the jaw is composed of two mandibular bones which are only partly fused together along their length (see the top-left drawing above). When one side grows slightly faster than the other, the jaw as a whole will start to curve from that point forward. As the image above show, the severity and final shape take all manner of crooked and scroll-like forms, arcing not only left or right but also upwards, downwards, or even into a spiral.

While photos of crooked jaws on living whales aren’t easy to come by, I did find several skeletal examples such as this one in the collection of the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. Here you can see the jaw not only curving to the left but starting to curve upwards and back onto itself.

Here are several more of the bizarre shapes that deformed lower jaws can take, sometimes curving along several planes at once.

Although Ishmael variously calls Moby Dick’s jaw scrolled and crooked, the phrase “sickle-shaped lower jaw” is maybe most telling in terms of the actual appearance Melville had in mind — perhaps something like the whale in that first photo, bent to the left with a bit of a curve upward? This would presumably still be memorable to any harpooners who battled him face to face, but on the lesser end of deformed such that the whale could still use it to “reap” Ahab’s jaw. (In case you were wondering, scientists don’t believe that crooked or scrolled jaws have any effect on a whale’s ability to hunt or eat, nor presumably attack belligerent ship captains).

2. Puncture wounds in the tail

In addition to a crooked jaw, Ahab notes in his quarter-deck speech that the whale has “three holes punctured in his starboard fluke.” The description initially seems to imply that the holes were the result of some stray harpoons, but later on we’re given the additional clarification that the tail appears “scalloped out like a lost sheep’s ear.” As I’m reading it, this would mean that the holes are really more on the end of the tail, scooped out in a half-moon shape. Needless to say, this is another peculiarity we almost never see illustrated.

This was a bit more difficult to find an illustration for, though this photo of a humpback whale’s tail seems to show a slightly “scalloped” left fluke.

Holes in the tails themselves also aren’t entirely uncommon, often the result of injuries sustained in fights with other whales or prey, or from getting caught in fishing lines or other gear. This humpback whale named Lure, for example, is frequently spotted throughout Canada’s Strait of Georgia, and the hole in his fluke makes it easy for scientists and whale watching tours to recognize and track him.

The only illustration I came across that appeared to show these puncture wounds is a painting by Gilbert Wilson, though it’s not entirely clear whether they’re ‘holes’ or just paint splatter. I say this because there are actually six holes in the tail (not three) and, for what it’s worth, none of his other images of Moby Dick have the punctures. But they are, for the most part, appropriately “scalloped” from the ends.

3. A “bushy” spout

Another way that Moby Dick is distinguished from other sperm whales it that he has a “curious spout… very busy, even for a parmacetty,” per Daggoo’s observation. “Aye, Dagoo” Ahab replies, “his spout is a big one, like a whole shock of wheat, and white as a pile of our Nantucket wool after the great annual sheep-shearing.”

It’s probably helpful to just see a sperm whale spouting as in this video from Dana Point, California. Note especially the roughly 45º angle of the spout and the position of the blowhole off to the left.

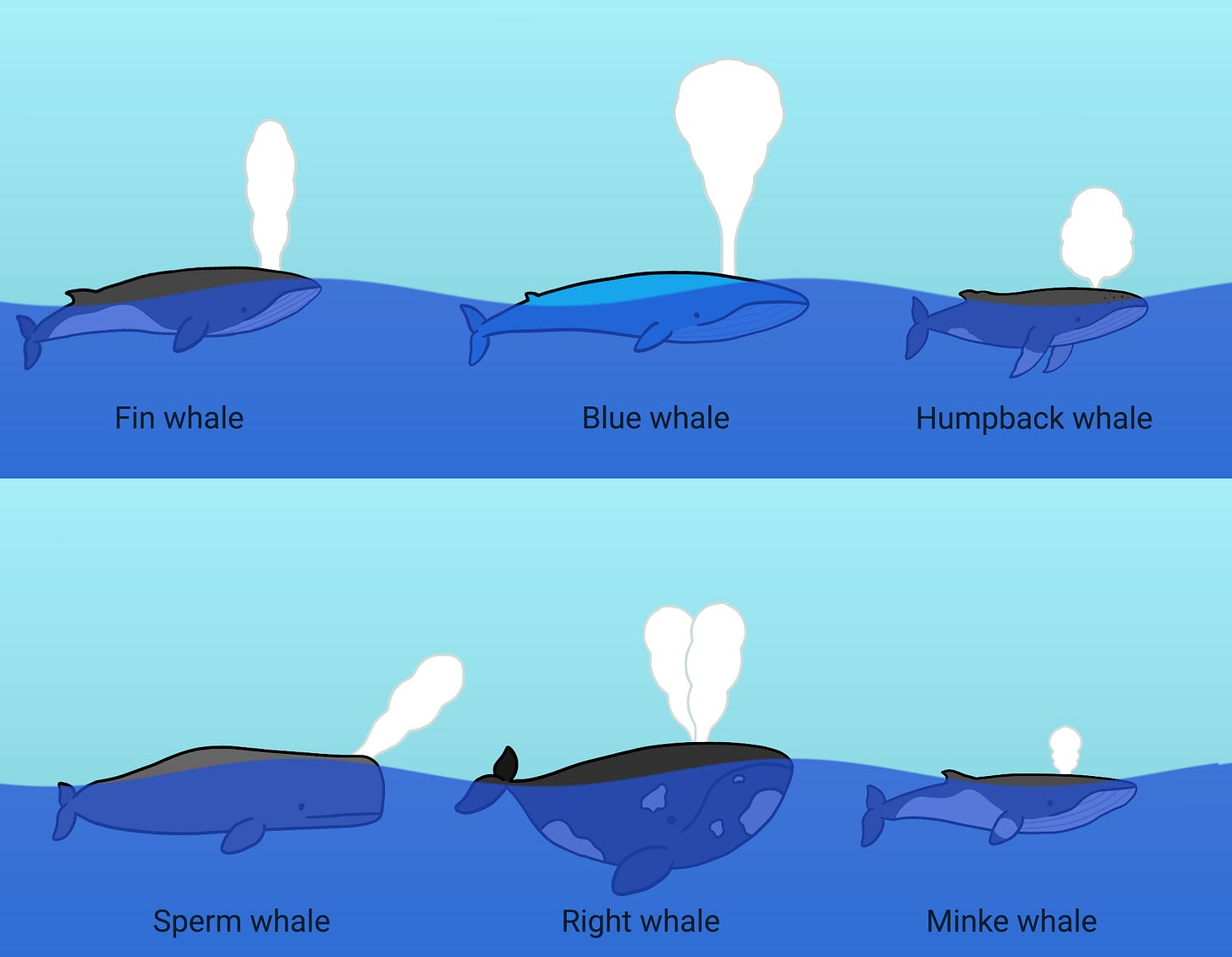

Hal Whitehead’s textbook on the species describes their spout as a “rather low, bushy blow for such a large whale, pointed forward and to the left.” Comparing it side-by-side to the blue whale, right whale, and others, it’s easier to understand how ships could distinguish between them from great distances.

If you’re curious about the how and why that this happens, the mechanics are laid out in this video which shows the difference in size between the larger left nasal passage which goes to the blowhole, and the right nasal passage which feeds into an air chamber to create the sperm whale’s “click” sounds. In fact, it’s this “convoluted nasal passage,” Whitehead writes, which is also the reason for the blow’s low height compared to other whales, “presumably because of a lower exhalation speed.”

Although Melville gives us an entire chapter on blowholes, there he only obliquely refers to the askew angle of sperm whale spouts, memorably writing that the “spouting canal [is] a little to one side… much like a gas-pipe laid down in a city on one side of a street.” A few chapters later he adds:

Unlike the straight perpendicular twin-jets of the Right Whale, which, dividing at top, fall over in two branches, like the cleft drooping boughs of a willow, the single forward-slanting spout of the Sperm Whale presents a thick curled bush of white mist, continually rising and falling away to leeward.

Moby Dick spouting isn’t common in the illustrations I’ve seen, though Rockwell Kent was especially fond of the composition and included it in at least four of his illustrations. He pays close attention to the shape, the “bushiness,” and even the forward-left angle. Perhaps out of necessity, though, he only drew a spout when the whale is breaching, a feat which to my understanding is technically possible though out of the ordinary.

4. An “uncommon magnitude”

Of all Ishmael’s hyperbole about whales, their size might be the most the most egregious and prone to exaggeration. In one instance, he writes that “a good sized whale” is about eighty feet long. He later ups the ante, saying that the largest sperm whales are “between eighty-five and ninety feet in length.” The skeletal whale at Tranque he estimates to have been “ninety feet long” in its fullest form. And when talking about the whale’s unappetizing length as a dish, he rounds it up to “nearly one hundred feet long,” a length he admits he hasn’t seen himself but accepts as true “on whalemen’s authority.”

Realistically, adult male sperm whales are only about 60 feet long, and the largest ever recorded is… well, actually still a matter of some debate. Depending on how much faith you put in 19th century whaling records, the largest ever seen may have been up to 85 feet long or over 100. One record from 1933 more believably claims to have measured a sperm whale at 79 feet, though even this enormous length is considered to be most likely a fish story. Despite Ishmael’s many affidavits and reliable sources, scientists now believe that 19th century scientists and whalers were likely measuring whales by every curve of their bodies, inaccurately adding to their length.

Moby Dick, however, is a sperm whale “of uncommon magnitude” and “uncommon bulk.” So for the sake of argument, and to make sure he’s properly uncommon, let’s call him an even 80 feet long, among the largest that have ever lived. For some sense of scale, though, at 80 feet Moby Dick would actually still be smaller than even the most cramped whaling ships. The Essex, for example, was about 87 feet long; the Charles W. Morgan, the lengths of which you can walk for yourself at Mystic Seaport in Connecticut, is 113 feet long. Whaleboats, for reference, were around 30 feet long.

It can be difficult for illustrators to convey Moby Dick’s size without some other surrounding context, most often the Pequod, a whaleboat, or the remains of Fedallah (or, erroneously, Ahab) tied to his body. Even then, it’s rare for artists to show a proportionate size instead of emphasizing the overwhelming difference in scale between the hunters and their prey. Take, for example, this Rockwell Kent drawing which, barring any illusions of perspective, shows the whale exactly as wide as the ~30 foot boat, basically double the width of what an 80 foot long whale would be.

5. A white, wrinkled brow

Another rarely-seen feature that jogs the harpooners’ memories is that Moby Dick has a “wrinkled brow” or forehead (to whatever extent a whale can be said to have a forehead). He’s elsewhere said to be “all crows’ feet and wrinkles,” not dissimilar from descriptions of Ahab’s wrinkled brow poring over the ship’s wrinkled charts.

This aspect of his appearance seems to have been on Melville’s mind early in the writing process, placing a checkmark next to this sentence in his copy of Beale:

The skin of the sperm whale, as of all other cetaceous animals, is without scales, smooth, but occasionally, in old whales, wrinkled, and frequently marked on the sides by linear impressions, appearing as if rubbed against some angular body.

Moby Dick’s forehead, though, is all the more unique because sperm whales, so far as I can tell, don’t usually have wrinkled heads. In fact, it seems that sperm whales are (or can be) wrinkled just about everywhere but their heads. I won’t claim to have exhausted the long Vaticans and street-stalls of the earth looking for wrinkly whales, but all I’ve seen are whales that are wrinkled right up to the point where you might say its head begins. In other words, an entirely (or even partially) wrinkled forehead really would be remarkable.

In general, this feature is included more often than some of the others, though it can be hard in certain contexts to distinguish wrinkles from scarring incurred in fights with giant squid and other whales. Here, for example, are depictions with variously wrinkled brows from Anton Lomaev, Garrick Palmer, and a mural at the New Bedford Whaling Museum by Richard Ellis.

6. Harpoon irons stuck in his back

In response to Ahab’s rousing quarter-deck speech, each of the three harpooners asks a question to help identify the particular whale he’s after (again indicating that just saying the “white whale” wasn’t enough). In Queequeg’s case, he asks whether the whale has “one, two, three—oh! good many iron in him hide,” twisting his hands around while searching for a word. “Corkscrew!” Ahab yells. “Aye, Queequeg, the harpoons lie all twisted and wrenched in him.” In other words, Moby Dick has several harpoon irons lodged in his body from previous battles with whalers.

A few chapters later, Ishmael personally attests that it actually wasn’t uncommon for 19th century whalers who may have been able to become “fast” to a whale during an attack but not close in for the kill. How the irons become twisted I’m not entirely sure, though sperm whales can dive more than 10,000 feet where the water pressure is 4,465 psi per foot. The wooden shafts eventually fall behind, but for whatever period they’re still attached perhaps their twisting in the water also twists the irons?

While its’s still hardly the norm, you do occasionally see stray harpoons stuck in the whale’s back, including in the mural at the New Bedford Whaling Museum (copied just above) and also in the 1956 film adaptation, where it’s Ahab fighting to his last breath instead of Fedallah.

7. Radney’s tattered red shirt

Harpoons in the back aren’t the only battle scars (or should I say trophies) that Moby Dick carries around with him. In Chapter 54: The Town-Ho’s Story, Ishmael tells the story of the Pequod’s gam with a homeward-bound whaling ship which had recently lost its own fight with Moby Dick. In the end, the first mate named Radney falls out of his boat and into the whale’s crooked jaw. The last thing its crew sees is Moby Dick swimming off in the distance “with some tatters of Radney’s red woolen shirt, caught in the teeth that had destroyed him.”

Granted it would be another six months or so before the Pequod would encounter Moby Dick off the coast of Japan, so one could reasonably argue that the tatters would have long since deteriorated or fallen away. But there are also plenty illustrations of Moby Dick that come long before the final chapters, or are outside of context entirely. It may not be the most significant detail about the whale’s appearance, but it’s arguably part of his appearance, and one that’s been entirely ignored.

8. A “pyramidical” white hump

When Moby Dick is spotted at last in Chapter 133, Ahab famously shouts: “There she blows!—there she blows! A hump like a snow-hill! It is Moby Dick!” The big white whale, naturally, has a big white hump.

Much ado is made over his white hump throughout the book, also described as a “high, pyramidical white hump” and a “great, Monadnock hump,” referring to the mountain peak in southern New Hampshire.

I’ve already spent some time looking into Melville’s habit of seeing whales in the shape of mountains (or is it mountains in the shape of whales?), and for what it’s worth, most illustrations do a more or less “pyramidical” white hump. But beyond that, take note not just of the particular shape of Monadnock’s white peak, somewhat offset from the rest of the mountain, but also the rest of its marbled aspect in winter as we move into our last category.

9. The (exact) whiteness of the whale

Moby Dick is famously white in color; albino even, at least in effect. He’s the white whale, and is referred to by that exact phrase more than 100 times. There’s an entire chapter on the whiteness of the whale all to belabor the point that his “colorless, all-color of atheism… shadows forth the heartless voids and immensities of the universe,” driving Ahab to his fiery hunt. You get it. The whale is white.

His unquestioned whiteness has also been reinforced by more than 100 years of illustrations, such that it’s typically the only physical trait mentioned in the book to which artists pay any real attention.

Well, not to be that guy, but actually this isn’t really what the book says at all.

It doesn’t take a close reading of the book to gather that Moby Dick is only partially white. Ishmael states pretty clearly that while his hump and forehead are indeed “snow-white,” the rest of his body was merely “marbled” with white streaks and spots. It was these specific features that earned him the nickname “white whale” as a kind of metonymy.

For, it was not so much his uncommon bulk that so much distinguished him from other sperm whales, but, as was elsewhere thrown out—a peculiar snow-white wrinkled forehead, and a high, pyramidical white hump. These were his prominent features; the tokens whereby, even in the limitless, uncharted seas, he revealed his identity, at a long distance, to those who knew him.

The rest of his body was so streaked, and spotted, and marbled with the same shrouded hue, that, in the end, he had gained his distinctive appellation of the White Whale…

Contrary to the impression left by repeating the phrase ‘white whale’ so many times, Moby Dick is only referred to as albino once in the book, at the very end of the “Whiteness of the Whale chapter” (“And of all these things the Albino whale was the symbol.”) It’s almost as if Ishmael becomes so obsessed by the color that he can’t help but exaggerating all the way to albinism. In his less crazed writing, though, Ishmael far more often calls out his two all-white features specifically: his “snow-white brow” and his “snow-white hump,”

Whether caused by age, injury, or genetic variations, what Ishmael (briefly) thinks of as albinism is more likely a form of leucism, or simply a lack of pigmentation creating white patches on the skin. Here, for example, are two unfortunately beached sperm whales with exactly the kind of white head and jaw as described, with those marbled streaks and spots on the whale on the right.

A book-accurate Moby Dick wouldn’t even be that rare. In 1972, Russian biologist Alfred Berzin published data he gathered while aboard industrial whaling ships around the world, finding that about two percent of whales had a “slightly whitish” head. Five percent were “slightly whitish” all over their bodies, suggesting a kind of marbling pattern as seen in this family of whales. Whiteness in and around their mouths is also a relatively common feature of sperm whales, which Melville alludes to in his description of Moby-Dick’s “bluish pearl-white of the inside of the jaw.”

There are plenty of examples of all-white whales, to be sure, including some with their own Wikipedia pages. Mocha Dick, the real whale written about J.N. Reynolds in the 1830s, is described as being “white as wool” and “white as a snow-drift” (both familiar comparisons). And that story is, of course, widely assumed to be one of Melville’s inspirations for Moby Dick. But when I read the actual descriptions given in the book, I have to conclude that Moby Dick did not number among these all-white whales. Could it be that Melville, in the same way that he thumbed his nose at landlocked whale anatomists and inept painters, intentionally made Moby Dick’s appearance more “realistic” than Reynolds’ all-white Mocha Dick?

If so, he may even have had in mind the real-life example of “New Zealand Tom,” which Melville read about in Frederick Bennett’s Narrative of a Whaling Voyage and which he mentions by name in Chapter 45: The Affidavit. Bennet wrote of Tom that he was “said to have been of great size; conspicuously distinguished by a white hump; and famous for the havoc he had made amongst the boats and gear of ships attempting his destruction.”

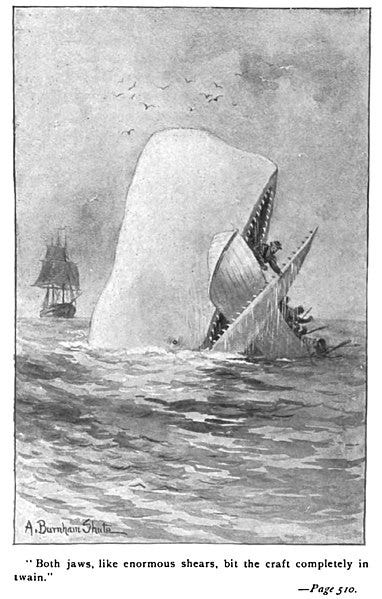

I hardly need to demonstrate with examples of illustrations that Moby Dick is always shown as being entirely white, plus or minus some artistic shading. The very first illustrated edition of Moby Dick, with four drawings by Augustus Burnham, was published in 1896, five years after Melville’s death. As has been the case ever since, Shute’s illustrations show Moby Dick as being pure white. Would Melville have even recognized him?

My interest in illustrations showing a book-accurate Moby Dick is more than just mere pedantry. Paying close attention to features like a white forehead and hump might even be the key to understanding Moby Dick. Consider, for instance, this 1998 article by Ben Rogers in the journal of an organization called the American Name Society (?!). With a bit of research that would feel right at home on this very blog, Rogers puts together all the clues and finds a missing link between Mocha Dick and Moby Dick, while at the same time connecting the etymology of the whale’s name to his white brow.

As it turns out, Webster's Dictionary is central to understanding the relationship between Moby and Mocha and Melville's emphasis on Moby's white hump. In Melville's edition of Webster's we find the entry: "Mocha-stone; Dendritic agate; a mineral in the interior of which appear brown, reddish-brown, blackish or green delineations of shrubs destitute of leaves." An uninspiring definition, but right above the Mocha entry is "Mobled; Muffled; covered with a coarse or careless head-dress," and also "Moble; To wrap the head in a hood." Nearby is also mob, its second definition being" To wrap up in a cowl or veil." By adding -y to mob as a suffix, where -y means 'having the qualities of', as in icy or snowy, we get moby: 'having the qualities of being hooded, veiled, or covered, especially about the head'. It is the sperm whale's broad head that Melville repeatedly emphasizes: "Human or animal, the mystical brow is as that great golden seal affixed by the German emperors to their decrees. It signifies-God: done this day by my hand.” Thus, the snow-white wrinkled forehead affixed to Moby's broad firmament of a brow makes him the "grand hooded phantom."

Rogers also emphasizes Moby Dick’s two white features as his claim to divinity and “ultimate inscrutability.”

Moby's pyramidical, white hump does indeed function better as a symbolic hieroglyph when contrasted with darker shades: it transforms the whale's brow into a diadem establishing his divinity, and it becomes the link — as a mobled hood — between his name, appearance, and ultimate inscrutability. […]

Whether or not there existed a real etymological relationship between these words did not concern Melville. His efforts were aimed at finding the accidents of striking orthographic similarity that enabled him to weave his linked analogies.

To draw Moby Dick as a more-or-less normal looking sperm whale would be almost blasphemous, but it would be more accurate to descriptions in the book. Aside from some white patches around his body, Moby Dick has just two singular white features: a white shrouded head, and a white pyramid on his back “like a snow-hill in the air.” It is Moby Dick!

There she blows!—there she blows!

So, reader, hast thou seen the White Whale? Has anyone?

It had bothered me for a long time that no one’s ever seen a faithful illustration of Moby Dick, and I decided it was time to take matters into my own hands — or rather, in the hands of someone far more artistically talented than I am. That is to say that I hired an illustrator through the freelancer website Upwork, providing a more condensed version of the above and, through a long process of revisions got something close to what I had in mind. Or close anyway, and then I tinkered around with the image on Photoshop until I could tinker no more.

That said, I did have to make some concessions. As Rockwell Kent seems to have figured out almost 100 years ago, there’s not a great, realistic composition that shows the full body of the whale while also lying at the surface of the water and spouting. Thus, I opted to get forgo the bushy spout. I also wanted to focus on the whale and not ask the illustrator to include a ship or boat to indicate a specific size, so you’ll just have to imagine this whale as measuring precisely 80 feet long.

So, without further ado, behold Moby Dick at last, an unusually large, crooked-jawed, wrinkle-headed, marbled sperm whale with three punctures in his right fluke, several twisted harpoons in his side, a snow-white forehead, a hump like Mount Monadnock in winter, and a piece of Radney’s red shirt stuck in his teeth.

…

…

[drumroll please]

…

…

Tada!

Alright, so it’s just a sperm whale with some blobby white patches, and you may have to zoom in for a few of the details. Is he a little less intimidating? A little less divine? He certainly looks older and wearier, tired of the Ahabs of the world throwing harpoons at him year after year.

I admit, it could be better. But you get what you pay for and this is a free blog, after all. But I hope this inspires someone with artistic talent to take this idea and run with it and maybe convince a future illustrator to take a chance on an almost unrecognizable version of the title character.

Let me know what you all think!

References

Aside from the hyperlinked sources in the article, here are a few more I relied on while pretending to be a whale biologist for the day:

A. A. Berzin, The Sperm Whale, 1972

Richard J. King, Ahab’s Rolling Sea: A Natural History of Moby-Dick, 2019

Kazue Nakamura, “Studies on the Sperm Whale with Deformed Lower Jaw with Special Reference to its Feeding,” Bulletin of the Kanagawa Prefecture Museum of Natural History, March 1968

James Nechas, Synonomy, Repetition, and Restatement in the Language of Moby-Dick, 1978

Sam H. Ridgway & Richard Harrison, Handbook of Marine Mammals Volume 4: River Dolphins and the Larger Toothed Whales, 1989

E. A. Spaul, “Deformity in the Lower Jaw of the Sperm Whale,” Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, May 1964

Janez Stanonik, Moby Dick: The Myth and the Symbol, 1962

Some would call you a madman but I applaud you sir !

I like the picture! The scrolled jaw in particular is quite creepy, and really adds to the appearance. And the white stands out all the more with the darker skin as contrast!