Herman's Head, Part 2: The Bust

; or, the rebirth of Herman Melville at 6 Pearl Street

In my last post, I began an investigation into the sudden disappearance of a bust of Herman Melville which, for approximately 20 years, marked the location of his birth in Lower Manhattan. Much to the disappointment of the many Melvilleans who have gone to pay tribute at the 17 State Street plaza that now occupies the space, the bust and adjoining plaque are now missing, removed and replaced with a dumb blankness, nothing but that broad firmament of exterior siding, pleated with riddles.

With the history of the Melvill family’s brief stay on this corner of the city out of the way, as well as catching up on the various tenants and addresses at what was once 6 Pearl St., it was time to learn more about the bust itself, including why and when it came to be.

It was a simple question which I found was littered with endless — and in some cases impenetrable — mysteries. “Speak, thou vast and venerable head,” I often demanded alongside Ahab, “speak, mighty head, and tell us the secret thing that is in thee.” It wouldn’t budge.

Herman’s Head—Contrasted View

We concluded last time in March 1990 when Thomas Heffernan, then chairman of the Melville Society, wrote to New York City Mayor David Dinkins’ office asking for help. The following year would be the 100th anniversary of Melville’s death, and the Melville Society was hoping to receive an official declaration of a “Melville Week” in the city to promote their slate of exhibits, lectures, and performances in his honor. Heffernan added as an aside that they would also appreciate if the mayor’s office would “intervene” on their behalf with the owners of 17 State Street, the building now occupying the site of Melville’s birthplace, to see if they would be amenable to the idea of erecting some sort of statue on its plaza.

The mayor obliged on the issue of Melville Week, so proclaimed in September 1991, but any response to the question about 17 State Street — if Heffernan got one at all — wasn’t archived among the records I requested from the city. But at some point in the 1990s it appeared just as suddenly as it would later vanish. Mysteriously, I could find no mention of its installation in contemporary issues of the Melville Society Newsletter from the 1990s, or anywhere else for that matter. I tried also to find archives of the ISHMAIL listserv from the early 1990s, though no one seemed to have saved them or have access to their ancient email accounts.

The earliest photo of the bust that I could find online was from 1997, when the wall intersected a small museum on the plaza called New York Unearthed (more on that later). Thus, I began with the (deeply unsatisfying) range of the bust’s arrival as happening sometime between 1990 and 1997.

The most obvious place to start was the clue on the bottom of the plexiglass protecting the bust while it was installed: "Casting of Melville's Head by William N. Beckwith." I sent an email to William — Call him Bill — and had a response literally two minutes later with his phone number. It was a level of generosity and helpfulness which would only grow over the next few months. In fact, much of this investigation wouldn’t have been possible without him so let’s all extend our gratitude in our hearts but also in the comments section.

I ran through my list of questions over the phone, starting with whether he knew what happened to the bust. He didn’t, but said he’d been asked about it several times over the years by inquisitive Melville fans, but it seems that’s where their searches ended.

Digging further, I was surprised to learn that the origins of the bust actually began long before 17 State Street. About a decade earlier, Bill received a call from his friend Jody Jaeger who was working on a PBS documentary about Melville called “Herman Melville: Damned in Paradise.” The producers needed some visual likeness of Melville to feature in the film apart from the handful of oil portraits and photos, but they needed it in just a few weeks. Jody suggested his buddy Bill Beckwith, who took the job.

“It must have been around 1983,” Bill told me. “We had just moved my bronze foundry/sculpture studio from Greenwood, Mississippi in the Delta to Taylor, Mississippi in the hills. I was teaching sculpture at the University of Mississippi part time and was Foundry Foreman for the Art Department foundry. Our studio in Greenwood had been broken into eleven times, and it was time to move.”

He had never read Moby-Dick, but looked to a very special copy of the book for inspiration. “I had my father's early, hardback copy of Moby Dick illustrated by Rockwell Kent and did some speed reading, and gathered some images of Melville from the library. I remember an oil portrait being very helpful.”

Bill recounted intricate details not only of his process in creating the bust but also his artistic intent and inspiration, trying to confer the feeling of being out on the open water. “I modeled the bust impressionistically in oil based clay, and pulled a plaster piece-mold. I had worked on a tow boat on the Mississippi River in the summers, and grown up on Lake Ferguson in Greenville, so know something about boating. I wet the negative plaster piece mold and painted in a wax positive mask, letting the wax form dissolve as it went to the rear of the head. It was supposed to give the feeling of spray in the face when traveling fast in a boat or ship, of being in a rain storm, or being one with the water.”

Bill got the bust shipped off to the filmmakers just in time — “still wet” as he said — looked after by Melville scholar Harrison Hayford and Patricia Ward, who was working with Hayford on the authoritative Northwestern/Newberry Writings of Herman Melville series. About a year later, the film was complete and scheduled to air on PBS stations across the country. The Associated Press said the documentary was “sculpted with care.”

Damned in Paradise

“Herman Melville: Damned in Paradise,” believe it or not, didn’t make it very far into the streaming era. Nor could I find any traces of it on YouTube or quasi-legal (ok, just plain illegal) torrent websites. Forced to interact with the real world, I found that a nearby community college had it on DVD and made a beeline to their library.

Scrolling through at quadruple-speed, I first spotted the bust perched behind Hayford during a talking head interview. Herman stares longingly out the window.

Shortly after, the bust get its big closeup moment in a panning/zooming shot in what is likely the best camera and lighting situation as we’re going to get. I made a sped-up, slightly clipped GIF, so behold at last the object of our monomania in all its glory.

In November 1984, shortly before the film premiered, the Melville Society’s quarterly newsletter published an article by Patricia Ward all about Bill Beckwith and the bust. Although there are a few small discrepancies with what Bill told me, it fills in a bit more about Beckwith’s background and process.

In the Spring of 1982, Bill Beckwith bought a copy of the 1930 Rockwell Kent edition of Moby-Dick at Patsy's Hodgepodge in Greenwood, Mississippi. The price was fifty cents. Bill recognized the book immediately. He had never read it all before, but he remembered seeing the silver embossed picture of the whale on his father's shelf.

A sculptor by trade, Beckwith had been staying in his studio since the roof leaked in the loft where he usually slept. With no bathroom, minimal lighting and a foam mattress, he lay on the floor and read Moby-Dick. Impressed with the power of Ahab, Beckwith decided to create a bust of Melville. "I wanted to see if I could cast a bronze that would convey, with some sensitivity and compassion, the spirit of this man, and yet contain in it the power of his work."

Before he began work on the bust, Beckwith studied all the existing paintings, photographs, daguerreotypes, and drawings of Melville. Working throughout the day and well into the night, he completed the sculpture in less than a month. The result is a kind of composite--a blend of faces and expressions, which most closely resembles the Melville of later years.

A recognized sculptor, Beckwith's work is currently part of the Smithsonian's traveling show on the "Art of Appalachia." He has received numerous awards and has been chosen to participate in several shows, including "Images ‘84" at the Louisiana World's Fair in New Orleans. Beckwith's talent has brought him a growing reputation and a steady flow of commissions; but he prefers to work on "projects that present an aesthetic problem to be solved in sculpture." "The Faulkner bust for the University Library gave me my first real challenge in portraiture. Melville was at least as difficult and enjoyable."

Many artists have tried to capture Melville's figure in paintings, drawings, and collages, but no one has endeavored to create a piece of this magnitude. Beckwith will cast the Melville bronze in the foundry which he built in Taylor, Mississippi. It will be a unique creation, for the mold will be broken after the casting is completed.

The Extracts article included two photos of the bust, which admittedly didn’t survive the low-res scans very well.

The article ends with a note saying that anyone interested in acquiring the bust should contact Patricia Ward, who it seems was taking a cue from Queequeg and peddling heads. But there were no takers, which we know not because anyone involved remembers what actually happened, but because there it is, sitting in Bill’s studio to this day. He sent along a few glamour shots as proof-of-life all these years later.

In case you, too, are scratching your head, what I learned is that this actually isn’t the bust that ended up at 6 Pearl Street. Rather, the one in the film was the artist’s proof, i.e., the first one cast from the mold which sculptors then use to make adjustments and refine details. But PBS had no time to spare, so Bill had to send off the proof to appear in the film, and sometime later it returned to his studio in Mississippi where it’s been ever since.

When Bill got it back, he decided to make some final adjustments and cast a second version just for himself. But that one didn’t stay on his shelf for long.

New York Underground

Bill’s memory on what transpired next wasn’t as clear, only remembering that a woman came to his studio sometime in the 1990s determined to buy the finished bronze bust. The asking price was $2,000; she said her organization, which he recalled was a small museum of some kind, could pay in installments — Melville and his kin forever debtors.

Amazingly, Bill remembered a small but notable detail some 30-40 years later: “For some reason, the word “tiacreft” sticks in my mind.” I tried to hear the shape of the word through the distortion of three decades but nothing in the Melville world was mapping onto the syllables. Later, when I returned to the history of 17 State Street it finally hit me: it was the group that had purchased the building in 1990, the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America—College Retirement Equities Fund, a retirement fund for teachers colloquially known as TIAA-CREF.

Because Bill’s memory had been so sharp on this point, I began to wonder if the small museum he mentioned might be New York Unearthed, the exhibit mere feet from the bust which, curiously, existed as a kind of vestigial appendage to the towering skyscrape. In short, when William Kaufman built 17 State Street back in the 1980s, he committed a bit of an architectural faux pas, neglecting to allow the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission to study the build site for possible archeological significance. The commission believed that the site might reveal items from the Jewish community which once lived at the corner of State and Pearl in the early 18th century. Kaufman’s punishment was to dedicate space on the ground floor of 17 State Street for an urban archaeology museum and fund it with $100,000 annually for five years.

Kaufman sounded exactly as thrilled about the prospect as expected, locating it not even on the building’s ground floor but in the tiny, detached corner of the plaza. “I don’t want to overstate it,” he told the New York Times, “it’s not going to be one of the great educational experiences of all time.” The team of archaeologists hired to lead the museum were eager to make the best out of the situation, noting that it would be the city’s first and only urban archaeology museum.

When it opened in October 1990, the Times called it “an intriguing if small new museum.” Designed by Milton Glaser (famous for creating the “I ❤️ NY” logo), it was run collaboratively by TIAA-CREF and the nearby South Street Seaport Museum. In just 1,600 square feet over two levels, the museum squeezed in several dioramas filled with mostly small domestic items found in New York’s soil both new and old: a 200-year-old beer bottle beside 6,000 year old stone points; 1950s lunch counter artifacts next to 3,000 year old pottery shards; 19th-century medicine bottles and children’s dolls from a early 20th century African-American community in Brooklyn. It was thousands of years of New York’s history collapsed into two small rooms, with a few bright-eyed archaeologists stuffed into the basement.

Before long, however, the museum became a relic itself. Kaufman sold the building to TIAA-CREF and funding from the building dried up right on schedule. Visitors to the museum, located not even a mile from the World Trade Center, vanished after September 11th. The museum was boarded up shortly thereafter and in 2004 the artifacts were hauled up to the New York State Museum in Albany. The museum sat empty aside from a 6-pounder naval cannon which had been dredged up from the harbor, apparently too heavy to move.

The open question still was whether the Melville plaque and bust had anything to do with this museum. The dates seemed to line up, it fit with Bill’s memory of a small museum, and the bust was, as you can see above, not even three feet from its front door. It also broadly fit the museum’s general area of focus — maybe not a archaeological find but a monument to the history of that exact spot. The trouble was that nowhere in any of the articles I found about the museum or in any of the archived versions of its website from 1990s through its closing could I find any mention of the bust or of Melville.

This was even more puzzling given that that the South Street Seaport Museum, which operated New York Unearthed, was very into Melville. Located just a few blocks northeast at 12 Fulton St, throughout the 1990s the Seaport Museum had a Melville Gallery and a Melville Library, it sponsored regular Moby-Dick programming and activities, and hosted the aforementioned Melville Week events orchestrated by the Melville Society. Their staff even included a Herman Melville impersonator named Jack Putnam, who performed regular one-man shows and led a walking tour of Lower Manhattan. He was, the New York Times wrote, “the official historian and unofficial conscience of the South Street Seaport Museum.”

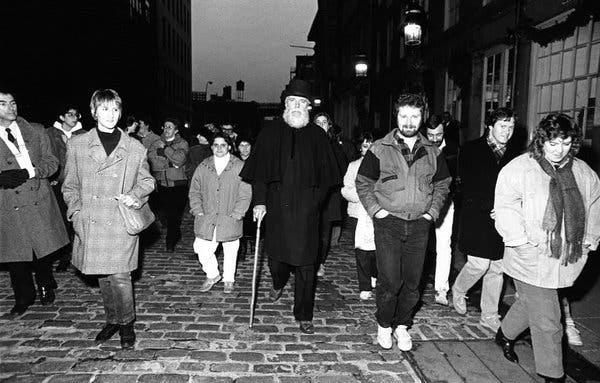

Here’s Putnam leading a tour as Melville, circa 1991:

When I reached out to the Seaport Museum, though, the librarian had nothing for me. They’d heard the questions about the missing bust before, but had no information about it anywhere in their archives. Curiously, the archivist added that “The area is outside the South Street Seaport Historic District, and we do not keep track of in general lower Manhattan public art installations,” perhaps indicating she was unaware of the museum’s role in operating New York Unearthed. I was unconvinced they were totally uninvolved, but I put a mental pin in it for the moment.

Herman Melville Reborn

Meanwhile, I was also having trouble reaching anyone at 17 State Street, currently owned by RFR Holding LLC, a real estate investment, development and management company which apparently has better things to do than search for missing Melville memorials. (This included some ongoing financial issues like a threatened foreclosure for not paying its lender).

So I returned to my question of when exactly the plaque and bust were installed, and exactly when they went missing. Having turned up no new leads, I accepted Bill’s previous offer to try to find his old financial records from the 1990s. I hadn’t wanted to ask him to dig through a jungle of filing cabinets but had little other choice. Once again, he came through within 24 hours, now equally as invested in the search as I was.

“Found my records from 1995!!!” his email began. Just as he had recalled in our first phone call, the bust was paid for in installments, beginning in June 1995 and ending with a final payment in November 1995. Along with these dates came something even more important: the direct buyer, per his records, wasn’t TIAA-CREF but the Berkshire County Historical Society, the non-profit that operates Arrowhead, Melville’s home-turned-museum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

Goods in (digital) hand, I called Erin Hunt, the curator/archivist at Arrowhead, to see what she could find. A few days later, she returned with two extremely helpful items.

The first was the BCHS Director’s Report from the January 8, 1996 board meeting where it was discussed that they had made final payment for the bust, a project which had been in the works “for several years.” It also revealed that BCHS had jointly purchased the bust with the Melville Society. TIAA-CREF, meanwhile, had contributed $1,500 toward the bust and the necessary installation work.

This note started to put many pieces of the puzzle together, but Erin sent another clip that had even more information: a scan from the BCHS newsletter from later that summer, announcing a tentative date for the installation of mid-September 1996. The announcement contained the names of several people involved in the planned celebration, including Where the Wild Things Are author/illustrator Maurice Sendak. (Sendak had recently illustrated Melville’s novel Pierre and, I later learned, was a friend to many in the Melville scholarly world.)

Another point of interest is that there were apparently plans to incorporate a giant Melville quote into a newly renovated plaza across the street at Battery Park, “a great quotation from Moby-Dick about Manhattan and the Battery.” I may have more on this another time, but suffice it to say that, unlike the bust, the installation never happened.

My eyes lit up at all the names in these two memos — Gordon Hyatt, Barbara Christen, Daniel Barron, even Maurice Sendak — people I could call and gather information and maybe even photos of this September unveiling. One by one, however, I discovered all of them were either no longer with us, were unable to help due to chronic illness, or simply didn’t recall. The archivist at the Sendak museum had no information about him traveling to the event. Nor did the Downtown Alliance, or the South Street Seaport Museum, which I pestered one more time to check records on left by Barron, a former curator.

Even weirder, though, no one I talked to had any recollection whatsoever of attending any events having to do with the installation, or even being aware that they happened. I contacted nearly two dozen Melville scholars who were active members of the community in the 1990s — nothing. Folks at both the Berkshire County Historical Society and Melville Society from that time, including executive directors and treasurers — nothing. Nothing from retired staff from TIAA-CREF, the South Street Seaport Museum, curators at New York Unearthed, or even the group that was simultaneously trying to install that quote at the Battery. As I mentioned, there was no mention of it in the Melville Society’s quarterly newsletter, which regularly announced meetings of scholars and other Melville-related events. The trail stopped cold with the information in the screenshots above.

From what I could tell, a small trust of organizations had spent several years organizing the purchase of the bust, obtaining funding, planning a celebration, and working with the building to install it… only for it to go up so quietly that it didn’t even rate a mention in the Melville Society newsletter. What’s more, due to the inevitable staff turnover at both organizations over 30 years, I discovered that the kind folks who today run the Melville Society and BCHS didn’t even know they owned this now-missing bust.

Just as quietly as Melville disappeared from New York City in 1891, he reappeared in 1996 without any fanfare whatsoever. It made absolutely no sense, and yet I’ve exhausted every possible lead in figuring out what happened. [Though please let me know if you know something!]

I hate to leave a mystery go unsolved, but at least I had the most basic answer for my question: the bust was installed in 1996.

The Spirit-Spout

On the other end, I already knew that the bust was removed sometime between when those two Google Street View photos taken, in September 2014 and November 2017. I suspected that discovering when it vanished would be a distinct clue as to why.

Members of the Melville Society’s Facebook page had previously speculated that it happened when the building was sold, but the building’s sale history doesn’t line up. It was sold in 1989 to TIAA-CREF; in 1998 to Steve Witkoff, and in 1999 to RFR, its current owner. Other said they’d heard it had to do with Hurricane Sandy which hit New York in October 2012, but we know it was there for at least two more years.

Finally, after scanning basically every search hit for “17 State Street,” I stumbled a comment left on an urban geography website called Privately Owned Public Spaces, which catalogs plazas like the one at 17 State Street. There, far away from the prying eyes of Melville enthusiasts, someone named David wrote that “The bust of Herman Melville was unceremoniously removed by workers on the evening of Tuesday, September 6, 2016.” Well that certainly pins it down! I wasn’t ready to fully trust the information, but it was something to go on for now. Others speculated that the removal might have coincided with the removal of the signage for New York Unearthed, which had been defunct for more than a decade.

A returned to the two Street View photos and a lightbulb turned on in my head. Here’s the plaza in September 2014, with the bust still visible beside the New York Unearthed exhibit:

And here’s another photo of the plaza taken in November 2017, where the New York Unearthed sign had indeed been removed.

The more significant difference, however, is the new sign on the wall reading IPSoft Plaza. At the time, IPsoft was one of the building’s largest tenants and had apparently acquired the naming rights to the plaza. As was becoming standard for this investigation, dozens of calls to past and present employees of IPsoft went nowhere. No one had any information about the sign, the plaza, the bust, the plaque etc., and this trail, too, went cold. But the coincidence was undeniable. The bust and plaque disappeared seemingly the same moment that the IPsoft Plaza sign went up.

I had one last thought: might there have been a building permit required to remove the bust, or to install the IPSoft sign? I downloaded a spreadsheet of all of the permits pulled by 17 State Street since 1991, but there was nothing for September 2016 — well, nothing but some plumbing and sprinkler repairs. A record for May 31, 2017 showed a work permit from a sign company, possibly installing the IPSoft sign. Ultimately, uncharacteristically, I decided to let this one go and not place a call to the company owner — though not before scouring their social media for any photos of the job. The important thing was that by late 2017 the bust was already gone.

One thing buoyed my spirits though: the IPSoft Plaza sign itself disappeared sometime between July 2022 and March 2023, possibly because IPsoft had rebranded as “Amelia” in October 2020. In other words, the wall is now completely bare and, if I was able to find the bust, there should be no reason preventing its reinstallation.

It was a long shot, but the real investigation was only just now beginning in earnest. I now knew absolutely everything I could about the location and the bust thanks to a Rolodex of librarians, Melville scholars, artists, and dozens of other folks who gratefully fielded my bizarre requests. I still had lots of people to contact, organizations to rally, and one person at 17 State Street who just might be the key to it all.

Next time Sometime on… All Visible Objects

I hope to be back in two more weeks with with part 3, but things are still unfolding as we speak! Otherwise, I’ll have another Melville mystery or two to tide us over.

Wow, this is incredible. Great stuff…anxiously awaiting part 3! Good luck!!

Great story, sleuthing and the writing it both brilliant. I'm hooked!