If you had asked me 18 months ago what I hoped to accomplish with this blog, I might have said something about having an informal, flexible space to pursue some silly questions; a reason to keep reading about Herman Melville and other related topics; or even just keeping my research skills sharp. The story of the Melville bust, though, has had some unexpectedly concrete — or should I say, bronze — outcomes.

Several times at the Melville Society Conference last week I found myself explaining the idea behind my blog, only to be asked if I had heard of the guy who found the Melville bust. Eventually I found it was the most tangible example of the kinds of thing I pursue here, especially being surrounded by dozens of intimidating (if exceedingly friendly) academics who have contributed much to the understanding of Melville and even to my own bookshelf. In any case, it’s an easier elevator pitch than explaining the connection between Melville and the Zodiac Killer.

Of course, the bust is just a small fragment of the Melville conversation happening in academia, in classrooms, on social media, and in book clubs. But on a personal level the investigation has been highly gratifying, not just because it was saved from languishing in a New York office building, or that people from all walks of life came together to help push this project to the finish line, it’s where it ended up — and I mean precisely where it ended up.

With the permission of Arrowhead, I’m very excited to share some photos of the bust in its final resting place which, I have to admit, makes me grin ear to ear every time I think of it.

Buuuuuuut first, before we get to that, there’s one last info dump I have to share in order to wrap up the whole investigation.

If you recall from earlier posts, I went to the ends of the earth to find more information about how the bust arrived at 17 State Street in the first place, including cold calling long-retired leadership of the Melville Society and Berkshire County Historical Society; contacting former employees of the neighboring archaeological museum and even businesses in the adjacent skyscraper, and bugging just about every Melville scholar who might have been invited to a celebration back in the 1990s. I’m sure I’ve blacked out several more hours of fruitless research and phone calls. I even asked the estate of Maurice Sendak, who I thought might have been present at the installation, to check his calendars from 30 years ago (they would not).

Well, mere minutes after publishing what I thought would be the conclusion of the series, a stray Google search on a different topic altogether led me to the whole story, published exactly where you’d expect to find it: the pages of the Melville Society Extracts. Yes, inexplicably, despite hundreds of searches worded in every which way, I never got a hit for anything in this particular issue from February 2001. All I can say is that maybe it was just outside the window of when I thought there would be chatter about it, and also, to my immense frustration, the Extracts are not readily — or at least consistently — searchable. Such is research.

On the plus side, just about everything I had deduced from my earlier efforts seems to have been borne out by the facts, which were provided in an article by Thomas F. Heffernan. One surprising new detail, though, was that the bust (or “mask”) wasn’t installed in 1996 as I thought, but two years later in November 1998. Otherwise, the opening paragraphs of Heffernan’s article, “The Melville Memorial at 6 Pearl Street,” should sound familiar.

On September 2, 2000, the New York Times carried an article stating that "Not a single monument or memorial ... exists anywhere in New York to the three native New Yorkers who just happen to be America's three greatest novelists: Henry James, Herman Melville, and Edith Wharton." After a word from this Melvillean, the editors ran, on September 15, a dutiful and precise correction:

"There is indeed a memorial to Herman Melville: a bronze bust with a plaque is set into the wall of 17 State Street at an outdoor sitting area and looks over the site of his birthplace at 6 Pearl Street."

The bronze mask of Melville, which was installed November 6, 1998, is the work of the Mississippi sculptor, William N. Beckwith, and will be recognized by some as the head of Melville seen in the PBS documentary, Damned in Paradise. It is recessed in the aluminum wall that bounds the public space behind the strikingly modern skyscraper known as 17 State Street. It stands exactly on 6 Pearl Street and is appropriately adjacent to, almost a part of, the tiny and fascinating archaeological museum, New York Unearthed.

Planning for a memorial of some kind on the site began in the days of the Melville Centennial Committee. The owner of 17 State Street, TIAA-CREF, was open to the idea of a Melville memorial when contacted in 1990, but advised that little could be done until the newly built office building was given a certificate of occupancy, since even a modest change in design would require application for a fresh planning permission from the city.

What I had never been able to figure out, though, is what happened to the bust between its appearance in the “Damned in Paradise” PBS documentary in 1985 and its installation sometime in the mid (or late) ‘90s. Where was Herman hiding? At Arrowhead, of course.

After its appearance on camera, Beckwith loaned it to Arrowhead where it stayed for the next eight years. Then, in 1993 as Heffernan’s plans to install the memorial at 17 State Street started to come together, Arrowhead held a fundraiser to formally buy the bust. Finalizing everything then took several more years, and for part of this time the bust was actually kept at the Central Park apartment of BCHS/Melville Society member Gordon Hyatt.

Heffernan continues:

Fortuitously, in the spring of 1993 Carolyn Banfield, then executive director of Arrowhead, announced that the Beckwith bust, housed at Arrowhead, was being offered in a fund-raising sale. It was a natural for the memorial. A campaign to raise the money for the purchase and installation of the mask was begun, and contact with TIAA-CREF was renewed.

The most enthusiastic support for the project came from Barbara Christen, vice-president of the Alliance for Downtown New York. She assembled at various meetings representatives of the Fine Arts Federation, the New York City Art Commission, the Conservancy for Historic Battery Park, and other bodies, and she performed the very helpful function of advising on the presentation I had to make to Community Board 1 for permission for the memorial. Jenny Dixon, the chair of the Arts and Culture Committee of Community Board 1, was thoroughly approving of the idea of the memorial. Gordon Hyatt, active in Arrowhead and a participant in the New York planning meetings, became the Melville mask's custodian in his Central Park West apartment while the installation project moved slowly forward.

A major contribution toward purchase of the mask came from Sanford Marovitz, and some money was left over from the Melville Centennial Committee, but more was needed to make the purchase from Arrowhead, not to mention to pay for whatever installation was going to be settled on. At this point, Richard Usas, a director of TIAA-CREF, volunteered to contribute to the installation money that TIAA-CREF earned from leasing the flashy new 17 State Street building for movie shoots. In the end the money from filming contributed to the memorial by TIAA-CREF came to $6,975, almost to the penny what was needed for completion of the project. In the final stages of the project TIAA-CREF was represented by Arend W. Taal of the company's real estate division.

Recruited through the good offices of Jack Putnam, Paul Pearson, director of exhibitions at the South Street Seaport, became the designer of the memorial, working with various proposals for display of the mask. Paul's sketches and cost consultation with fabricators constituted a massive contribution of effort on the memorial; his design work continued after he left the South Street Seaport to take a comparable position at the Brooklyn Children's Museum. No one put more into the appearance of the memorial than Paul.

Two successive building managers at 17 State Street, John Finnigan and Joseph Barnes, were not only cooperative in the design and installation of the memorial, but were as enthusiastic as everyone else working on the project. It was, in the end, Joe Barnes who undertook the actual engineering of the installation: the bust stands, recessed in the wall, behind a 20" by 22” window of half inch thick clear lexan; the enclosure is an anodized aluminum box sealed on all sides with an opaque plexiglass panel on top to allow filtered ambient lighting for the bust.

To the left of the display window an inscription on a lexan plaque reads:

On this site, number 6 Pearl Street, HERMAN MELVILLE was born August 1, 1819. Author of Moby-Dick, "Bartleby the Scrivener,” Pierre, Billy Budd, and many other American classics.

Time, many supportive friends, cash, and patience put it there. One hopes that it receives the approval of the honoree. He does look good.

After nearly 30 years, the bust is back at Arrowhead once again.

Speaking of Arrowhead, let’s look at the bust one last time from its origins all the way to where it stands today. (Call it a “mask” all you want — I’m in too deep.)

Here it is as it looked in 1985, fresh from Beckwith’s studio, in the 1985 documentary:

In 2001, which we now know was just a few years after its installation, one visitor to the 17 State Street plaza found Herman looking seasick and even a bit forlorn. It’s hard to believe it’s the same sculpture.

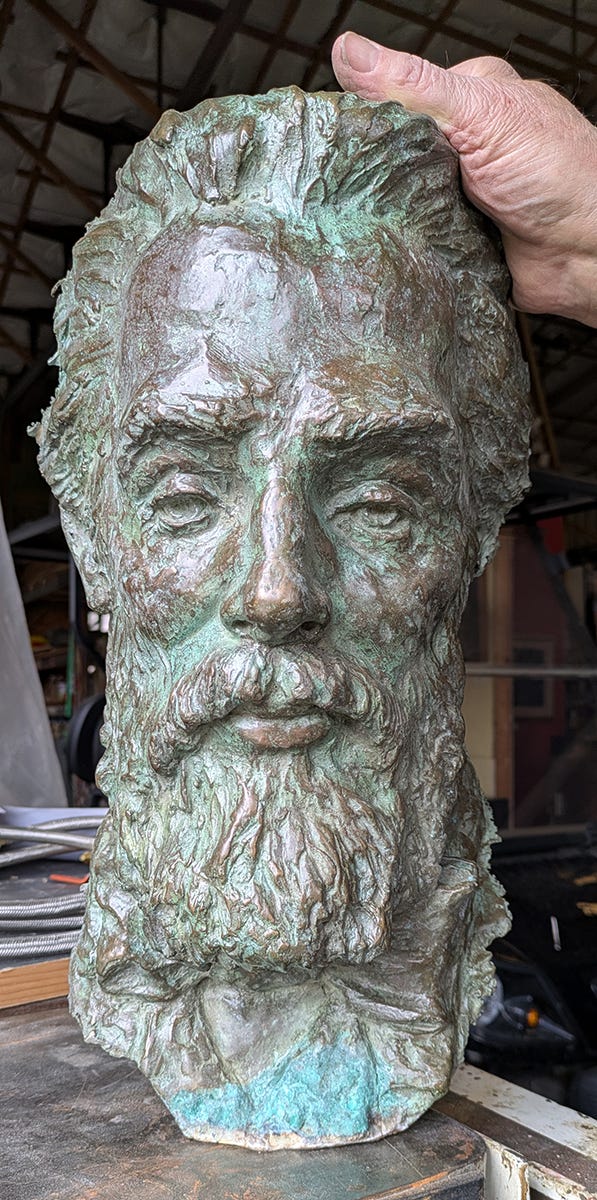

He wasn’t in much better shape in our first look at it after convincing the building manager to ship it back to Arrowhead, looking gaunt and lifeless though slightly Jesus-y, if you ask me.

Things were looking up when the folks at Arrowhead opened the box, though the poorly-packaged wooden base had broken in half. He’s still quite green and was especially discolored at the base, but in the right lighting you could at least see a glimmer of what it once looked like.

These photos I’ve already shared, so here’s what’s happened since.

While the bust was en route to Arrowhead, I started poking around for someone local to Pittsfield who might be able to help restore it to whatever extent was possible. We had no money to make this happen but that, as I like to say, was tomorrow’s problem. I quickly found the website for sculptor and painter Andrew DeVries, who lives nearby in the Berkshires. I mentioned the name to Lesley Herzberg, executive director of the Berkshire County Historical Society/Arrowhead, and lo and behold, she informed me that his mother-in-law was an archives volunteer at Arrowhead for thirty years. Andrew agreed without hesitation to help us with the project (so please visit his website and buy a print or some postcards).

Along the way, I facilitated some emails between Andrew and Bill Beckwith, which allowed me to eavesdrop on questions that only bronze sculptors know to ask, such as:

Would rewaxing it darken the patina?

Is what looks to be “aggressive bronze disease” the result of casting a steel plate into the metal?

Was the original patina was a potassium sulfide with perhaps a ferric overcoat or maybe a “cupric” (??)

Andrew shared some photos for illustration, like this one of the “bronze disease.”

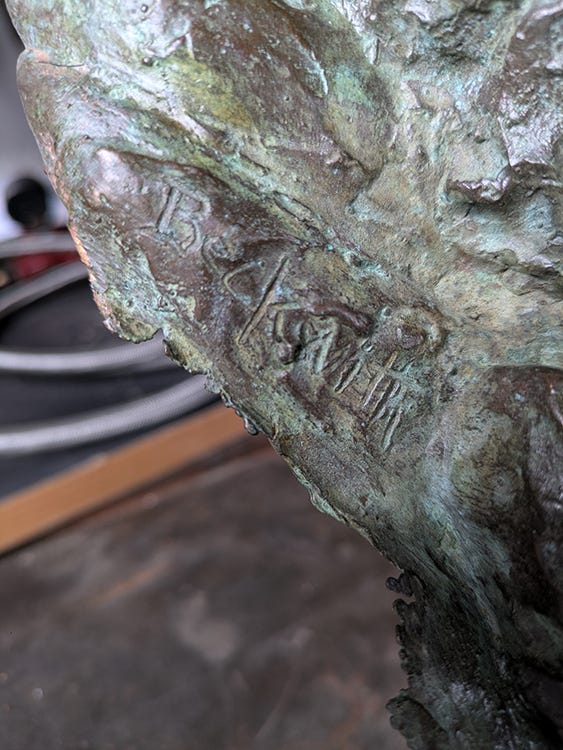

He also sent this closeup of Bill Beckwith’s signature, which presumably hadn’t seen the light of day since it was installed in 1998.

Whatever the answers to his questions were — or whatever the questions meant in the first place — Andrew delivered it to Arrowhead looking pretty spectacular.

Once at Arrowhead, I had imagined the staff might stick in the barn by the gift shop, or even on the chimney mantle if they were feeling cheeky.

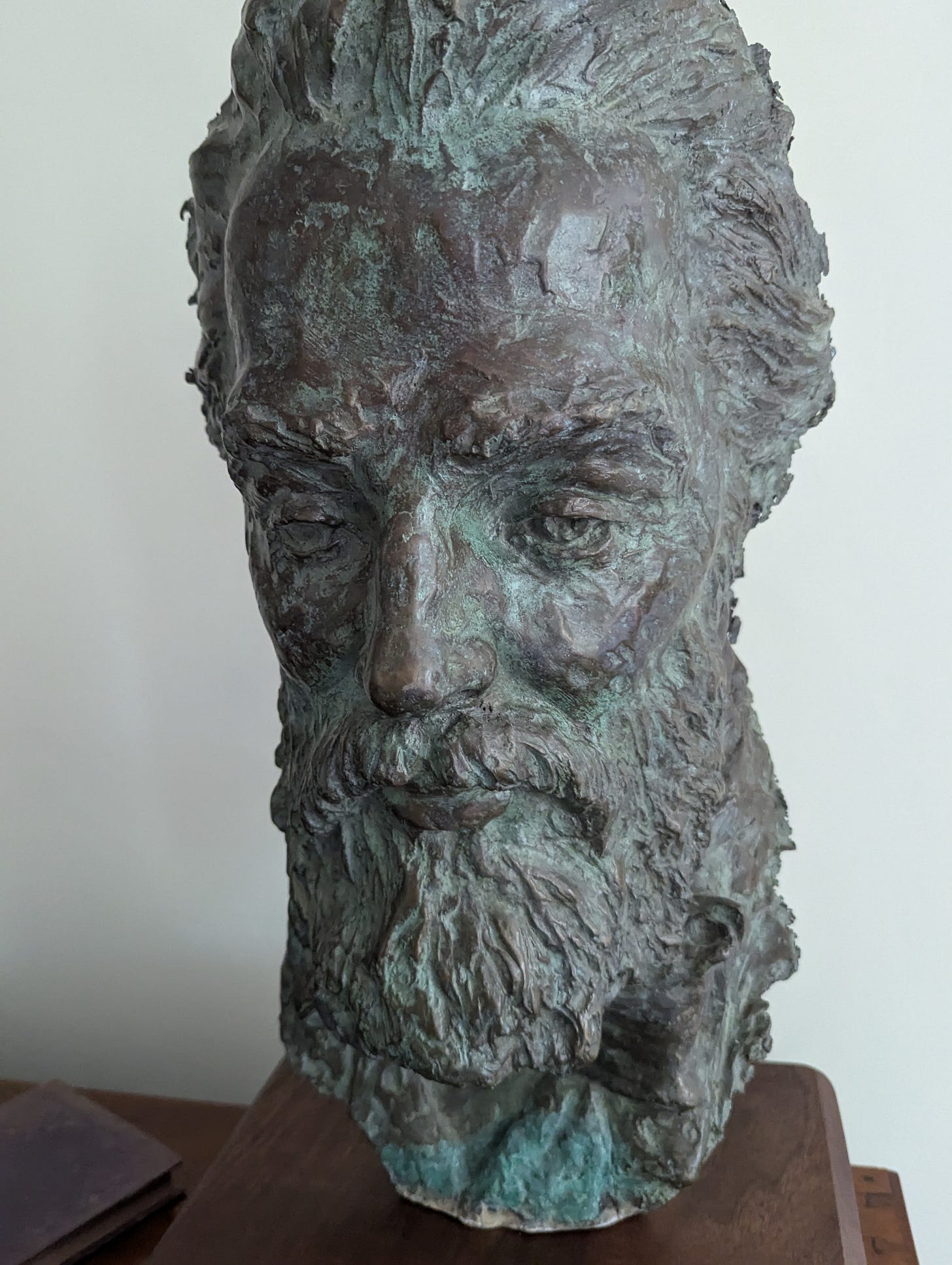

It hadn’t even occurred to me to imagine it would be placed here in Melville’s study, mere feet where he sat down to write Moby-Dick as he looked out at Mount Greylock. I can still hardly believe it.

Matt Wall, the Arrowhead tour guide who sent me these photos (and who I got to meet at the Melville conference!) said that when the guides get to the room they even mention this blog and the investigation that recovered the bust. It’s all very wild.

In any case, if you aren’t too sick of looking at Melville’s bronze mug, here are some final close-ups of it in situ where I hope it will stay for many decades to come.

Incredible work on this whole series. I'm impressed and inspired.

Wow, it looks fantastic in its final location! And I have to admit, I'm very fond of the green patina. It looks ancient and weatherbeaten, like it's spent some time on a ship.