Moby-Dick is a notoriously difficult book to adapt to a visual, live-action medium for any number of reasons. Whether a film, a miniseries, a play, or an opera, even if an adaptation finds a clever way to turn dozens of encyclopedic chapters and extended poetic soliloquies into passable dialogue, you’re still faced with a huge, white dilemma: how do you deliver on the promise to show a man battling an enormous whale in its final moments? It’s a Chekov’s Gun of levianthic proportions.

But even where the big budget productions have succeeded to produce a believable whale (well, kind of), I always find they lack the playfulness of the language and peculiar sense of humor which, for me at least, is really the heart of the book. I’ve yet to see an adaptation which takes a moment to malign Frederick Cuvier’s terrible scientific illustrations (“not a Sperm Whale, but a squash”); or which finds a place for the wealthy New Bedford fathers who give whales for their daughter’s dowry “and portion off their nieces with a few porpoises a-piece.” Don’t bother looking for the cows standing with their feet “in a cod’s decapitated head, looking very slip-shod.” It is, to almost every first-time reader’s surprise, oftentimes a very silly book.

So I ask you: what better format for an adaptation than a radio play, where the ships, rigging, whales, and chases are all conjured in the imagination? And who better to write and perform it than the National Lampoon, a group of irreverent, over-educated satirists and (I say respectfully) absolute morons? Even better, what if I told you it was a musical?

OK, so the word ‘adaptation’ is doing a lot of work here, but sometime last year I came across a YouTube account which just a few days earlier had uploaded something titled “National Lampoon Radio Hour: Moby! The Musical,” originally aired in September 1974. Naturally, I had a lot of questions. For one, I was unaware that National Lampoon even had a radio show, or that they wrote and performed musicals on it. It also sounded to my ears like it had been digitized straight from the master tapes, not a bootleg recorded on someone’s stereo. Then, just as suddenly, the videos were gone. (I had, of course, downloaded all 19 tracks all immediately, knowing they wouldn’t last long). My interest jumped up to yet another level.

What was going on here, I wondered, and what is this musical? Why would a magazine better known for its boundary pushing and often intentionally offensive satire write and record this half-serious tribute to a Moby-Dick? It’s a spoof, to be sure, but at 25 minutes long with a cast of nearly a dozen performers, it’s no throwaway joke. My moby-sense, if you will, was tingling.

Now, before I get into it, I’d be remiss if I didn’t state at the outset that writing fondly about one sketch by National Lampoon shouldn’t be construed as a general endorsement. Its output, from the magazine to the stage and radio shows and movies are very much a mixed bag, and writing about them entails a lot of careful tiptoeing around some awkward and even abhorrent material.

But if you can ignore that for a moment, let’s look back at the time that the staff of the Lampoon called a ceasefire on their pet targets (and also their pet targets) and sang their hearts out for the sorrow of Captain Ahab. It was a moment that some of them would be reminiscing about fondly for decades.

The Lampooneers

To back up a bit, although National Lampoon is mostly remembered today for its magazine and movies like Animal House and Caddyshack, music was part of its lifeblood almost from the start. With its origins in one-off parody magazines in the late 1960s, its Harvard-educated founders sneered at narcissistic musicians, hypocrites, and sell-outs, and in the aftermath of the summer of love it was like shooting fish in a barrel.

It didn’t hurt that they had some talented impressionists within its growing network of comedians. Within two years of the magazine’s debut in April 1970, National Lampoon released an album titled Radio Dinner, skewering ‘60’s idols like Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and the Beatles, mocking their post-breakup antic and political grandstanding. Best remembered from the album is the track “Magical Misery Tour” which spoofed Lennon delivering a blistering musical rant aimed at his fans, bandmates, and peers while asserting Yoko and himself as “supreme intellectuals.” (While you’ll reel at some of the language, in this case much of it was taken almost word-for-word from Lennon’s 1970 burn-it-all-to-the-ground interview with Rolling Stone.)

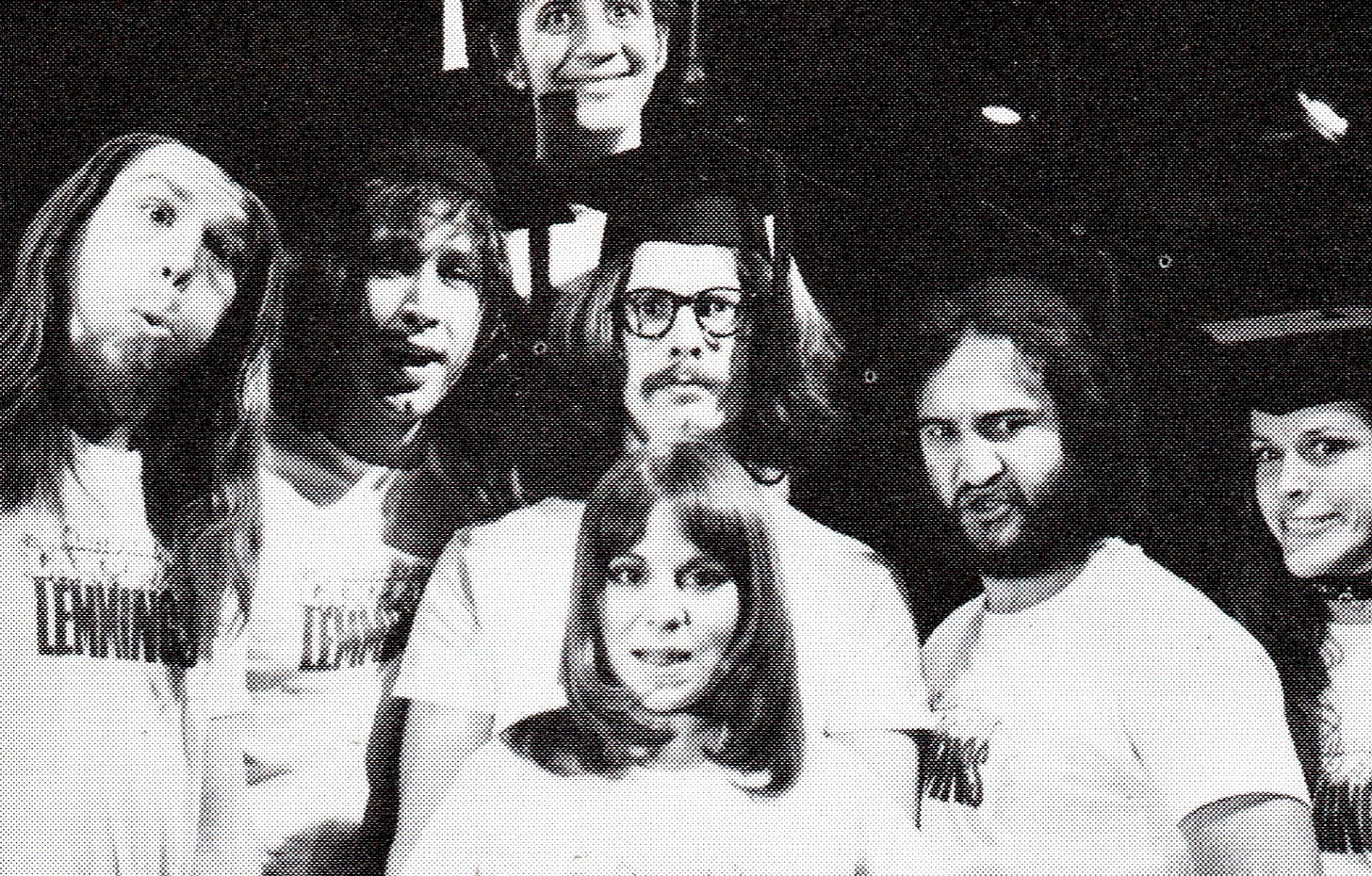

National Lampoon went even bigger in 1973 with its off-broadway stage show Lemmings. Billed as "a satirical joke-rock mock-concert musical comedy semi-revue theatrical presentation," its second act was a full-fledged Woodstock parody with performers like Chevy Chase, Christopher Guest, John Belushi getting in their last jabs at the 1960s. Acts included a faux-Temptations quartet singing "Papa was a Running Dog Lackey of the Bourgeoisie” (with lyrics taken straight from the Communist Manifesto); Bob Dylan, then in his cowboy/country phase, singing “Positively Wall Street;” and a stinging caricature of Joan Baez and other white musicians/activists who loudly supported the Black Panther protests in Oakland — from safely across San Francisco Bay.

Lemmings became an unexpected phenomenon, running for 350 performances at the Village East and further extending the National Lampoon brand. But it was also a massive a drain on the organization’s resources to keep a stage show going night after night (not to mention a disastrous attempt to take the show on the road during the 1973 oil crisis). The cast was bounding with ideas and talent, but the physical and financial burden of running a theater show was unsustainable.

Founding writer/editor Michael O’Donoghue approached Lampoon’s publisher with an idea to solve their problem while keeping all of their new and wildly popular talent in-house, proposing a weekly radio show modeled somewhat tongue-in-cheek on those that ran in the Golden Age of Radio of the 1930s and ‘40s. Not only would they be free of the costs and hassle of producing live theater, the cast would also be free to pursue virtually any zany idea they wanted whether in the form of a sketch, song, fake ad, news segment, interview, call-in show.

Thus was born the weekly, syndicated National Lampoon Radio Hour, distributed for free primarily to college stations, recouping their costs with a share of the ad space. The show debuted on November 17, 1973, appropriately beginning with its unofficial theme song, “You Don't Have to Look at Pictures on the Radio.”

So don't tell them what you look like on the radio

'Cause if they never see you then they'll never know

Doesn't matter if you've acne 'cause they'll never know exactly

What you look like when they listen to the radio

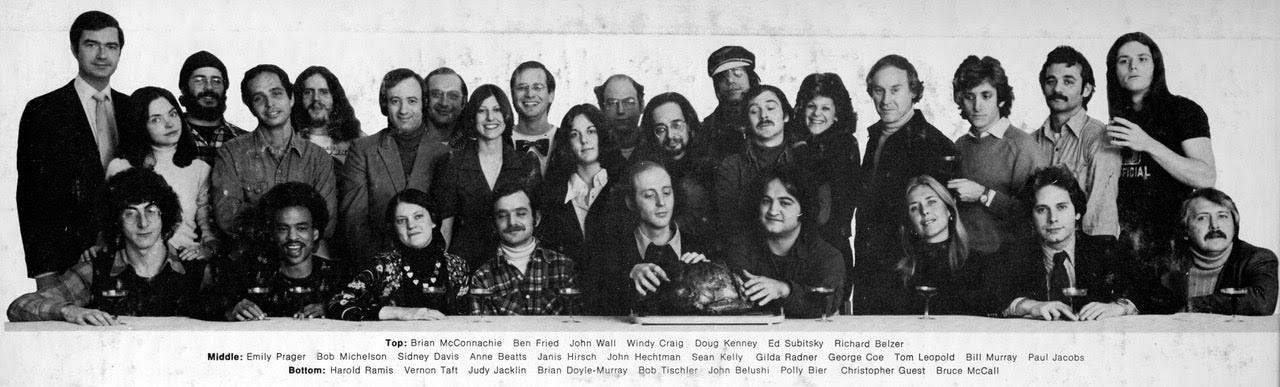

The show featured sketches and musical parodies from the magazine’s growing stable of writers, a veritable who’s-who of 1970s comedy which soon added stars like Bill Murray (younger brother of Lampoon writer/performer Brian Doyle-Murray), joined by more Second City alum like Gilda Radner and Harold Ramis.

Audiences, typically young college students, ate it up. Initially syndicated in 84 markets nationally, this number eventually ballooned to around 600 stations with millions of dedicated listeners, eclipsing the reach of the magazine. Even after their largest national commercial sponsor abandoned the show in response to a sketch about the assassination of Richard Nixon, and the dramatic exit of O’Donoghue over some misunderstanding, the Radio Hour trudged on, buying time with reruns and still delighting drunks and stoners across the country. According to Lampoon publisher Matty Simmons, on some campuses the show would air on Saturday night as “a thousand or more kids would gather around loudspeakers, drink beer, and listen” — an almost unbelievable scene to imagine in 2025.

Selling Moby

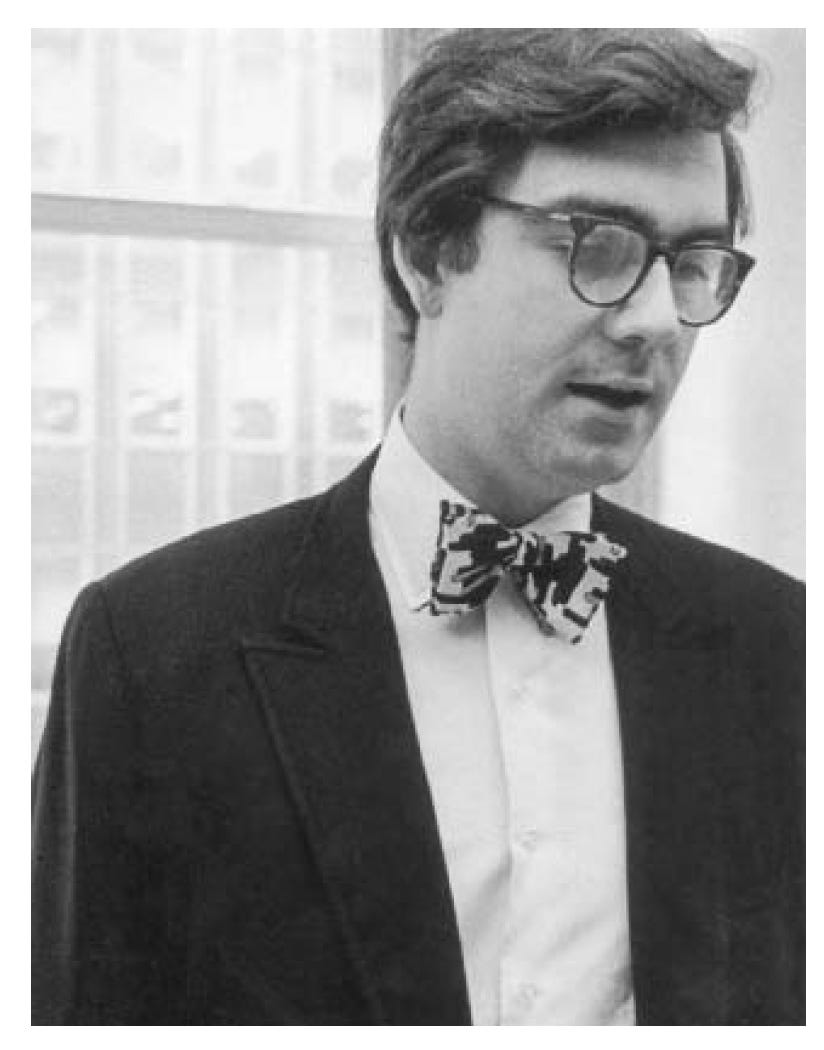

By the fall of 1974, the Radio Hour, long since cut down to a half hour to keep up with the grueling production schedule, was under the creative direction of longtime Lampoon contributor Brian McConnachie, a man who looked and dressed more like an English professor than the head of an off-color, foul-mouthed radio show.

Coming out of a summer break of rehashed material, McConnachie pitched an unconventional idea to signal the show’s fresh start, away from the toxic in-fighting between staff that had characterized its first year and permeated its increasingly caustic sense of humor, both stemming largely from O’Donoghue. There was perhaps no one better positioned than McConnachie to lead the way. In the Lampoon’s self-mythologizing, McConnachie is often described as existing in a world all his own — possibly extraterrestrial, and specifically from the planet Mogdar — whose aloofness and off-kilter ideas had kept him outside the ego-driven feuding.

I can only conjecture that McConnachie’s idea to launch the second season must have received some puzzled looks. It was, of course, a musical retelling of Moby-Dick, as if performed by an earnest if not-so-talented local theater group, specifically the Little Worth Community Theater in Sabbathday Lake, Maine, the last remaining active Shaker community in the world. The idea was alien in more ways than one.

Despite their highly-educated backgrounds, literature was never a frequent target of the Radio Hour aside from a recurring Masterpiece Theater-type spoof they called “Front Row Center.” The joke was the same in each of the 2-3 minute long pieces: a stuffy academic would give a long, serious introduction to a classic novel or play, followed by some absurd reinterpretation. In Waiting for Godot, the title character shows up and apologizes for being a few minutes late (his bus never came); for Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, Bill Murray follows the introduction with one of his favorite nonsense bits, screaming:

"Everybody get outta here, there's a lobster loose! Ohhhh, holy cow, he's loose! Everybody get outta here, he's vengeful! Quickly! Cover yourself with hot butter and carry lemons just in case you have to squirt him with it and so forth, to repel him! Everybody get out of here quickly, there’s gonna be a tragedy! Oh god!”

Moby-Dick it ain’t and, on the whole, sketches on the show were decidedly more low-brow and/or acerbic, such as “Exorcist Oscar Acceptance Speech,” “What If Ed Sullivan Were Tortured?”, and “Terminal Football,” a pre-game pep talk in which a football coach informs each member of the team individually of their recent diagnosis with a terminal illness.

McConnachie’s Moby-Dick musical, running for the entire half-hour show, was relatively playful and silly, and a breath of fresh air for the show. “Rules about who could and could not work on the show were gone,” writes Lampoon chronicler Josh Karp in his 2006 book about the group. “The result was more fun than McConnachie had experienced in his working life, and he became enraptured with the process of putting Moby! together.”

Having acquired the rest of the cast’s buy-in, the show was put written and rehearsed over the course of a week at National Lampoon’s radio studio. McConnachie contributed the story and dialogue while Sean Kelly came up with song lyrics. It was all set to music composed by the group’s senior copy editor, the musically-gifted Louise Gikow. The songs were meant to evoke everyone from Gilbert and Sullivan to Stephen Sondheim. McConnachie praised them both in a December 2010 interview with the New York Public Library, calling Gikow “a very accomplished pianist… when she wasn’t correcting the typos in our porn.” Kelly he compared to “an incarnation of Lorenz Hart, and I’d throw in W. S. Sullivan as well.”

The joy in the pure silliness of it was infectious. “The more we did it, we fell in love with the process,” McConnachie remembered. “We actually became those people we were mocking,” referring to the original idea to mock the ‘Golden Age of Radio,’ which for at least this brief moment turned into a celebration of it. Per Karp’s history of the group, during the recording sessions McConnachie “would run to the hallway and fall to the ground laughing uncontrollably at what they were creating in the studio.” Nothing tickled him more than Belushi’s performance as Ahab singing a Porgy and Bess–style number to himself on deck.

Moby! The Musical

All that said, I don’t want to oversell the degree to which Moby! faithfully tells the story of the book. To summarize, and hand pick its best parts, Ishmael, played by Tony Hendra, is still the newcomer to the ship, initially playing coy with his name before declaring in a waltz:

Call me Ishmael, salty young dog of the sea

Call me Ishmael, that’s what my name is and sailing my game is

So call me Ishmael, and I will answer to thee.

Not Zeke, Zachariah, Jonah, Jeremiah

But Ishmael, that’s me

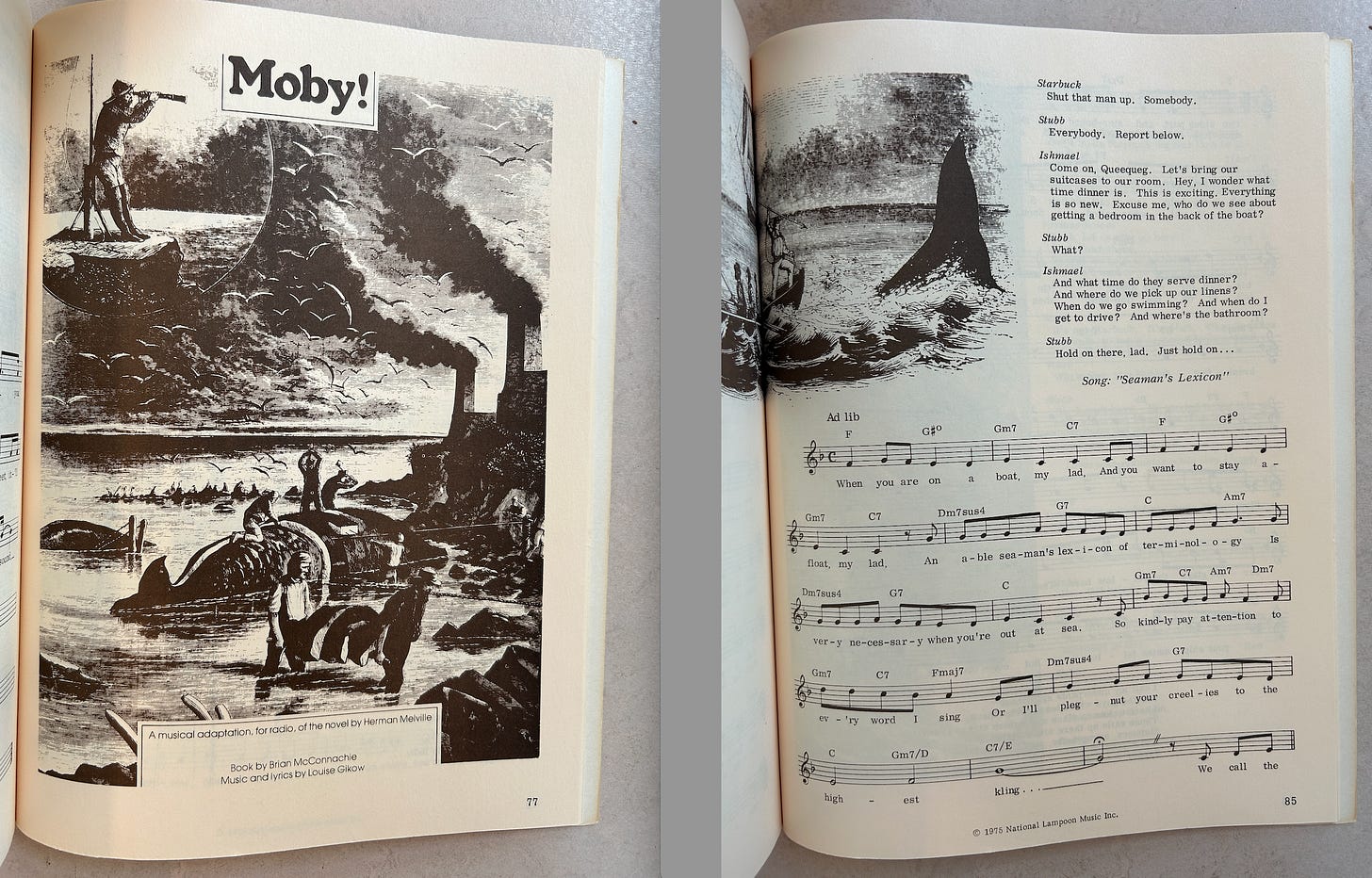

Ishmael and the rest of the crew are bossed around by Brian Doyle-Murray as Starbuck and Brian McConnachie as Stubb, who teaches the newbie about the special lexicon of the sea. The song, which you might say stands in for some of the most encyclopedic chapters of the book, begins with some halfway accurate lingo before collapsing into mostly nonsense.

When you are on the boat, my lad / and you want to stay afloat, my lad

An able seaman’s lexicon of terminology / Is very necessary when you’re out at sea

So kindly pay attention to every word I say / Or I’ll plegnut your creelies to the highest kling

We call the two sides port and starboard / And the backside is the larboard

We don’t say help, we call out SOS

Say biscuit for your bread / Go pee-pee in the head

And breakfast is a mess

And that’s a ducklick that you’re wearing / And a star is called a bearing

And the floor is always called a deck unless

You’re aloft around the flop side, when you have to call it topside

And luncheon is a mess

ISHMAEL: Luncheon too?!

Stubb orders the crew to go below deck so that the brooding Ahab, played by John Belushi, can walk the deck in peace. Ahab’s leg was of course bit off in an encounter with Moby Dick but more importantly, he lost his wallet along with it. He’s now behind on mortgage payments on the ship. Worse, the crew forgot that it’s his birthday and is nowhere to be found.

Today is my birthday / I turn sixty-three

When they’re in their berth they / Don’t dream about me

Ahab they’ll ask you, who’s he? / I’m the unhappiest person man at sea

When he bit my leg off, I’m certain Moby knew / That in my pants I kept my money.

Now the mortgage payment on my ship is due.

When I lose my “vessile” to bankers in town / I’ll sink and I guess I’ll most probably drown.

And then I’ll certainly be / The unhappiest man at sea.

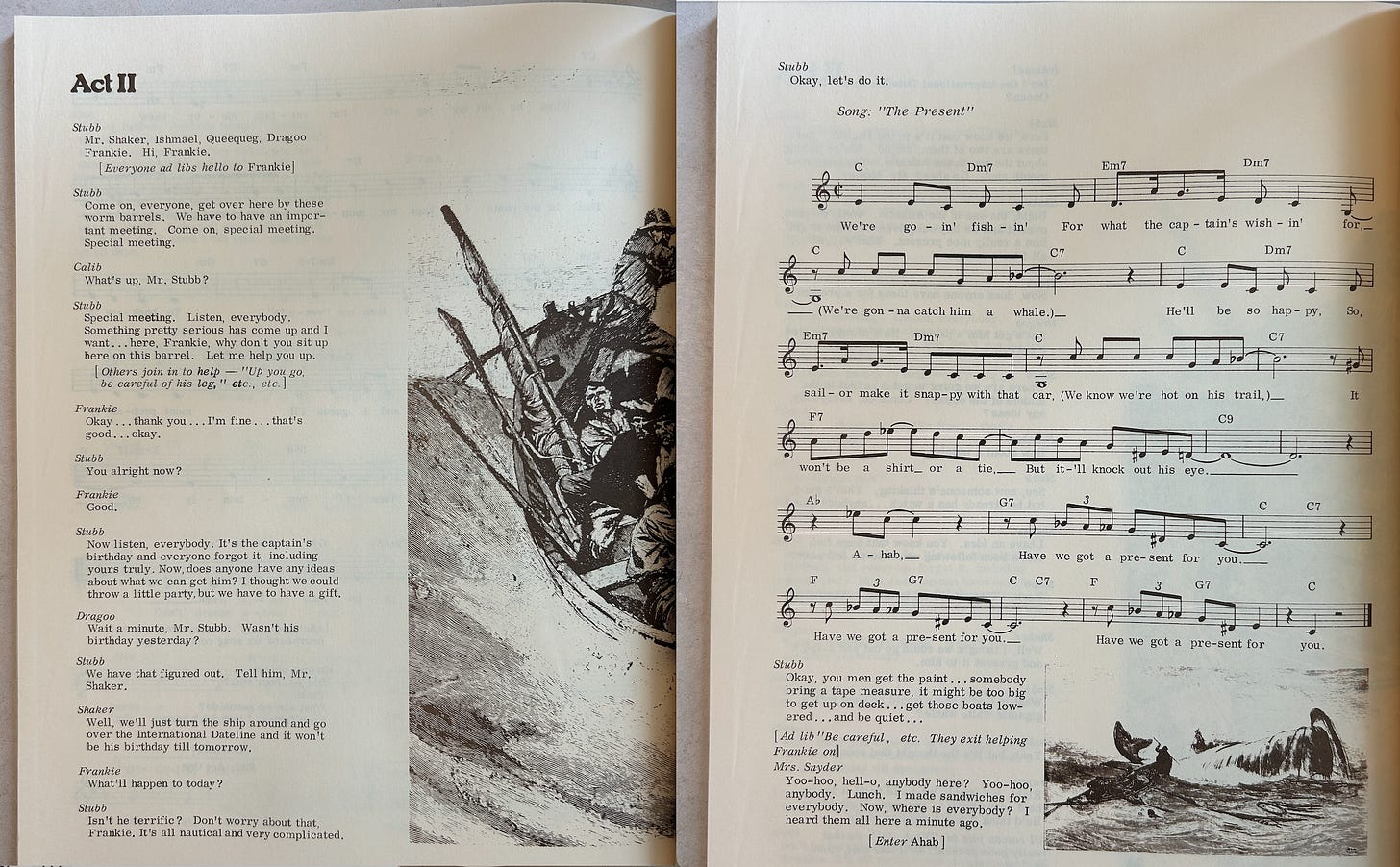

Below, Stubb realizes that everyone forgot Ahab’s birthday and they brainstorm some ideas of what to get him. A parrot? A watch? A character named Shaker suggests they get him something a little bigger: “You know that huge fish that’s been following us since we left port?” Stubb is intrigued. “Yeah. That stupid white thing. What about it?” “Well, I thought we could go out and catch it and present it to him.” And by then it’s time for another song:

We’re going fishing for what the captain’s wishing (we’re going to catch him a whale)

He’ll be so happy, so sailor make it snappy with that oar (you know we’re hot on his trail)

It won’t be a shirt or a tie / But it’s knock out his eye

Ahab! Have we got a present for you

Things go a little off-the-rails when Ahab meets Mrs. Dorothy Snyder, one of the sailor’s aunts who was still on board when the ship left port. The pair begin flirting and sing a duet called “You’re Never Too Old to Love.” There’s also a green hand named Frankie, played by Emily Prager, who the rest of the crew is (as Lampoon biographer Josh Karp puts it) “continually attempting to bugger.” As I warned, it’s National Lampoon — of course parts of the show aren’t going to hold up well.

Meanwhile, the crew has successfully killed Moby Dick off-stage, not even warranting a song, and prepare to present it to Ahab. Ishmael spots another ship coming toward them and Ahab confesses to being in arrears. In fact, the ship is the finance company coming to repossess the ship. Stubb says they have their own confession, surprising him with the dead whale. Recognizing Moby Dick, Ahab reaches into its mouth and finds his leg with the money still in his pocket. The ship is saved and he celebrates with the final song:

Moby, we’re such a perfect match / I was all at sea, you got hooked on me

Moby, you weren’t an easy catch — natch!

You may look like a monster to a landlubber

Moby, you ain’t heavy, you’re my blubber!

Moby, fanciest fish a-float / I was just a wreck, till you came on deck

Moby, welcome aboard our boat

You won’t be a pariah now that I’m standin’ by ya

Moby, you’re my leviathan

The episode concludes with the complete list of cast and crew and canned clapping. No torturing Ed Sullivan or exploding heads or needling the political corpse of Richard Nixon. The excerpts above are just my particular favorite sections, but you can hear the entire 25-minute show here, albeit in a slightly grainier version.

Postscript

“Moby! the Musical” premiered on September 28, 1974 and if nothing else, audiences shook their heads at the courage it took to produce such an episode. “Where else, but on the Radio Hour is anyone experimenting, taking a chance, failing in order to succeed?,” wrote the Montreal Gazette. “Where else are people with brains actually using those brains? Where else is anyone laughing? It’s all happening each week, including a modern musical called ‘Moby’ where Captain Ahab has a thing for that whale.”"

That said, the alien takeover of Radio Hour wasn’t meant to last. After just a few more episodes, Belushi took over the show as creative director and McConnachie returned to writing for the magazine. Then, after just twelve more episodes, it was decided that the Radio Hour had run its course. The cast and writers were not only burnt out by the rigor of the weekly production, but within a few months a large number of its staff would be poached by Lorne Michaels for the debut of his new late night sketch show, then called just Saturday Night. In fact, more than half of that season’s cast came from National Lampoon, including O'Donoghue, the original producer of Radio Hour who departed just before “Moby!”

The staff mostly moved on, but this still wasn’t the end of the material; National Lampoon’s publishers were nothing if not experts at repackaging old bits. By 1975, just five years after the magazine began, they had already put out seven anthologies, and the massive changing of the guard provided an opportunity to wring out old pieces one last time. Among these was the National Lampoon Songbook, a special edition of the magazine sold separately on newsstands featuring sheet music and lyrics for the group’s favorite material from their albums, tours, and Radio Hour. Among these was “the complete script, lyrics, and music of the mini-musical Moby!”

Original copies of the Songbook are now somewhat rare and expensive on eBay, but lucky for me (and you) my local library has a sizable collection of sheet music. There on the shelf, tucked between Mozart’s marches and Offenbach’s operettas, I found National Lampoon’s winking tribute to Moby-Dick down to every last note and stage direction, arranged for the benefit of enterprising high school theater clubs and, I suppose, the sheer joy of pushing a dumb idea to its absolute limits.

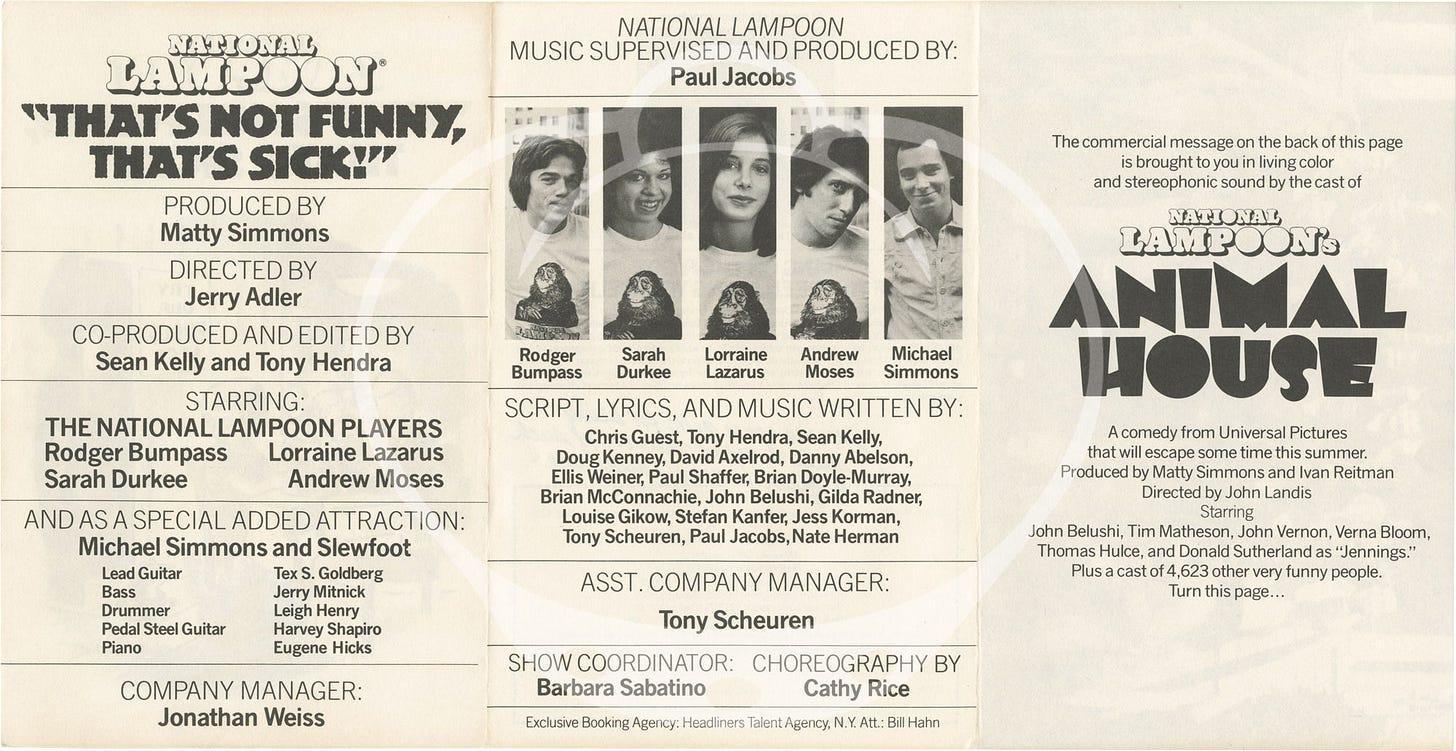

The whale’s last gasp occurred in 1977 when it was performed as part of yet another touring comedy stage revue called “That's Not Funny, That's Sick.” With the original cast gone, the show was made up of a rotating case of newcomers like Eleanor Reissa, Wendy Goldman, and Rodger Bumpass, who later made his name as the voice of Squidward on Spongebob Squarepants.

Although there are no recordings that I could find, a Washington Post review of the show in October 1977 indicates that it still focused largely on parodies of the musicians like John Denver, Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, James Taylor, Neil Young and Diana Ross. But the show still found time for a condensed version of Moby! and it’s “show-stopping number: Call Me Ishmael.”

Several decades later, McConnachie (who recently passed away) was still playing his favorite moments from Moby! to audiences and cracking up as he listened along with them. At the NYPL panel interview in 2010, he was just as enamored with Belushi’s performance as Ahab as he was in the studio in September 1974. "This is an expositional song in the plot,” he explained to the audience before pressing play, “and please do pay attention—you can hardly miss it—but at the end the way he holds onto that note.”

Blink and you’ll miss it, but for a fleeting moment the raunchiest and most offensive ensemble of comedians came together to pay a sincere tribute to Moby-Dick. All it took was handing the reins to a bespectacled visitor from Planet Mogdar.

Thanks/References:

Thank you to Mark Simonson for his help and his website chronicling the history of National Lampoon! Other work I relied on for this post includes:

Judith Jacklin Belushi and Tanner Colby, Belushi: A Biography, 2005

Tony Hendra, Going Too Far: the Rise and Demise of Sick, Gross, Black, Sophomoric, Weirdo, Pinko, Anarchist, Underground, Anti-establishment Humor, 1987

Josh Karp, A Futile and Stupid Gesture: How Doug Kenney and National Lampoon Changed Comedy Forever, 2006

“Harold Ramis,” On Story—Screenwriters and Filmmakers on their Iconic Films, 2016 (ed. Barbara Morgan)

Dennis Perrin, Mr. Mike: The Life and Work of Michael O’Donoghue, 1998

Ellen Stein, That’s Not Funny, That’s Sick: The National Lampoon and the Comedy Insurgents Who Captured the Mainstream, 2013

Bravo!!! Thanks for another fine and fun investigation. Guess I either missed or forgot about Moby Dick on the old Radio Hour. Great to see and hear it now, here. Back then we duly treasured those National Lampoon albums, loyally bought at Hot Poop ("Walla Walla's only bing-bang record shop"). All I can recall about whales was that bit with Bill Murray and Christopher Guest as "Ron Fields." "Whaling songs are the best." Ha, now on YouTube ofc

https://youtu.be/akQ6NgP1avI?si=qbHbQtgI4Dxpu1FS