In the early chapters of Moby-Dick, one of the more trenchant (and often comic) themes comes from the tension between the deep-seated religious values of the Pequod’s owners, Peleg and Bildad, and their unrelenting pursuit of profit. But in the context of whaling, it’s not the conflict of the proverbial rich man trying to get into heaven which forces them into mental gymnastics, but rather the compromises they’re forced to make with the deeply unreligious, profane, and even pagan crew.

For instance, Peleg and Bildad initially refuse to let the cannibal Queequeg onto their ship, let alone sign him up for a voyage. They let their guard down only slightly after Ishmael’s half-hearted lie about his friend’s conversion to Christianity (belonging to “the great and everlasting First Congregation of this whole worshipping world”), but any remaining concerns are quickly tossed aside after Queequeg demonstrates his skills with a harpoon. And in Bildad’s Christmas morning farewell in Chapter 22, he sends the ship off with the wise yet waffling counsel: “Don’t whale it too much a’ Lord’s days, men; but don’t miss a fair chance either, that’s rejecting Heaven’s good gifts.”

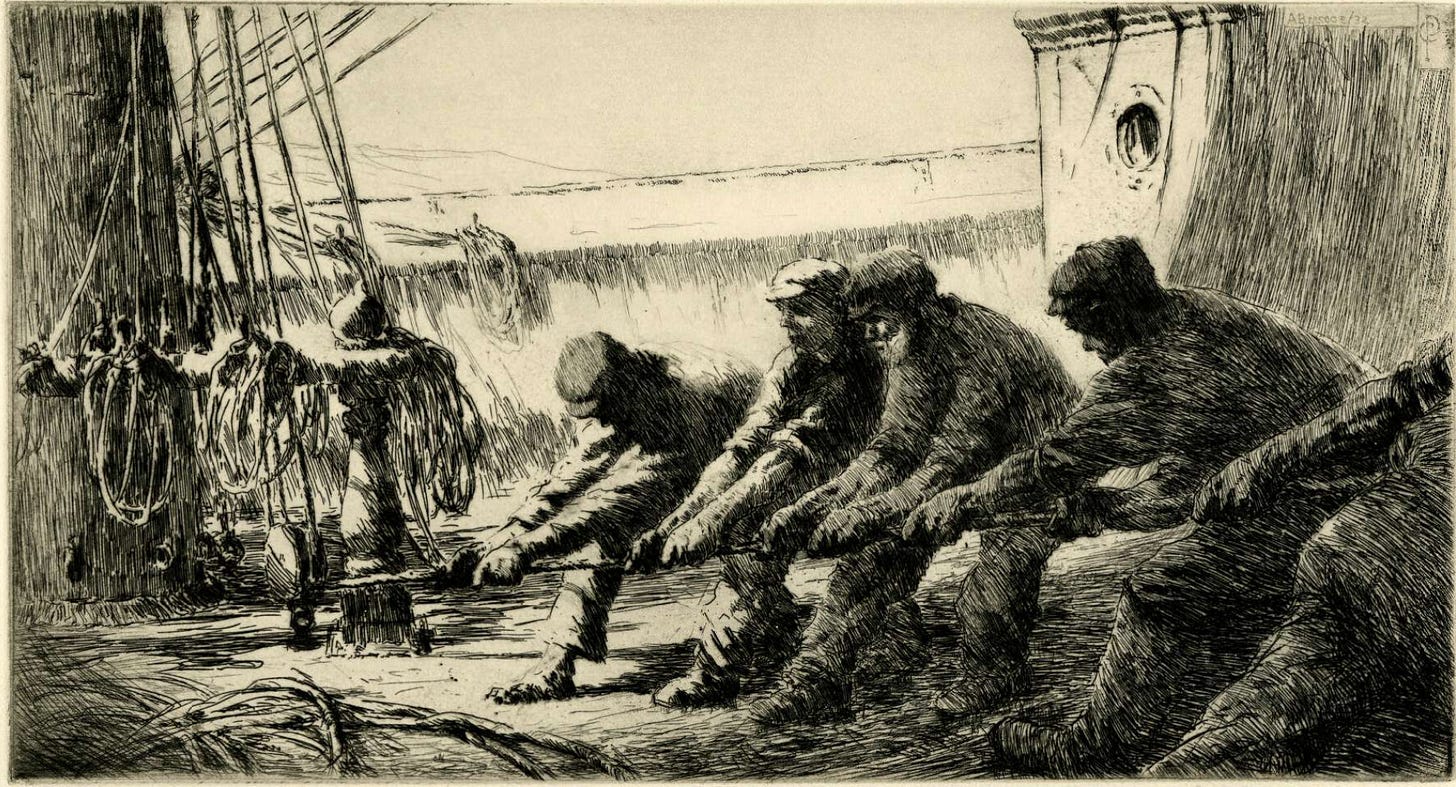

But this clash of the religious and the profane is most fully on display slightly earlier in Chapter 22, when the crew is heaving at the windlass to raise the anchor. Bildad stands by and sings a “dismal” psalm to cheer on the crew — or maybe it was to drown them out. Because meanwhile, the crew “roared forth” with their own song, a sea shanty which Ishmael describes as “some sort of a chorus about the girls in Booble Alley.” (Apparently the crew hadn’t yet received Bildad’s warning that “no profane songs would be allowed on board the Pequod, particularly in getting under weigh.”)

And this is what ye have shipped for today. While the nature of who these girls are and why you might find them in a place called Booble Alley is probably self-evident, I had a feeling there was a lot more to unpack than the slivers provided in footnotes. A turn of phrase that odd and (call me immature) still kind of funny was one that deserves a deeper dive.

Haul Away Joe, Haul Away Rosie

As always, I began my research by checking all the usual annotated suspects. And while most editions at least squeamishly insinuate the meaning of “Booble Alley” as 19th century sailor’s slang for a red light district, a few found it too scandalous to even provide that information. The Hendricks House annotation really beats around the bush, describing it only as among “the lowest and most abandoned neighborhoods frequented by sailors” and letting our imaginations do the rest.

Charles Feidelson Jr.’s note goes only marginally further, writing that it was a “Sailor’s name for a street in a depraved neighborhood, specifically in Liverpool.” Willard Thorp, editor of the Oxford University Press’ 1947 edition, writes that it was merely a “pestilent lane.” And while this isn’t untrue — the areas, as we’ll explore later on, were areas known for depravity of all kinds — in the context of this snippet of a song, these all arguably miss the point. Thankfully, the editors of the Norton Critical Edition are comparatively blunt, at last explaining to readers that the phrase was a “Sailor’s name for a slum street frequented by prostitutes.”

More to the point, the Norton annotation also tells us that the specific song “has not been identified.” One wonders, however, whether the Norton editors are being overly cautious here, as the editors of the Longman Critical Edition more confidently note that the song was “probably the shanty ‘Haul Away Joe,’ with its line, ‘The gals o’ Booble Alley’” — so kudos to editors John Bryant and Haskell Springer, who explain even further that Booble Alley was specifically a street in Liverpool’s red-light district. But more on that later.

As evidence for the song’s identification, Bryant and Springer cite a 1985 article by Stuart M. Frank in the New England Quarterly, titled “‘Cheer'ly Man’: Chanteying in Omoo and Moby-Dick.” Frank, in turn, cites a 1967 book called Sailortown by Stan Hugill, a British folk musician and sea music historian. In fact, Hugill was known in his time (1906-1992) as the "Last Working Shantyman," having served as the leader of sea shanties on British ships in the 1920s and 30s.

Hugill has a lot to say about shanties in general, “Haul Away Joe” included, starting with something of a defense of Booble Alley. Despite the squalor and debauchery of the area surrounding the Liverpool docks, Hugill wonders: “Seaman must have thought these Booble Alley girls were better than most, for did they not sing in one of their famous fore-sheet songs:

Ye may talk about yer Havre gals, an’ Round-the-Corner-Sallies,

Way, haul away, we’ll haul away, Joe!

But they couldn’t go to tea wid the gals o’ Booble Alley

Way, haul away, we’ll haul away, Joe!

In other words, the (French) girls from Le Havre have nothing on the girls from Liverpool.

In his book, Hugill provides just this one verse from the song — one version of one verse, really. Take a listen to the slightly longer version below, as recorded by folk musician (and, strangely, pioneer in computer science) Stan Kelly in 1958, replacing Joe with Rosie and Johnnie. This version also features a second verse about the beheading of King Louis XVI during the French Revolution, which for some reason became a frequent part of various versions of the song.

Talk about your harbour girls around the corner, Sally

Away, haul away, haul away my Rosie

Away, haul away, haul away my Johnnie-o

But they wouldn’t go to tea with the girls from Booble Alley

Away, haul away, haul away my Rosie

Away, haul away, haul away my Johnnie-o

King Louis was the king of France before the revolution (Away, haul away…)

But the people cut his head off and it spoiled his constitution (Away, haul away…)

Well now I’m leaving Liverpool bound for the Bay of Mexico (Away, haul away…)

I thought I heard the Old Man say it’s time for us to roll and go (Away, haul away…)

Taking a step back, the exact origins of Haul Away are unknown, but it’s variously dated to either the early post-Napoleonic era (c. 1815) or slightly later in the 1830s as a variation on the blackface minstrel song “Jim Along Josey.” Notably, that song had a similar refrain of “Hey, Jim along, Jim along Josie! Hey, Jim along, Jim Along, Jo.” What’s important for our purposes though, is that in both cases the song seems to have been established by the late 1830s/early 1840s when Melville spent his time at sea and could have become familiar with it.

Again, the lyrics to shanties were frequently changed, improvised, and otherwise not thought of as being particularly set in stone. Shanties in particular were prone to these lyrical and melodic changes, evolving in extreme isolation at sea before being passed on to the next crew like an extreme game of telephone. Historians of sea music have adapted to this issue by indexing songs based on common lyrics, ideas, melodies, and their usage on the ship rather than one strictly based on the name alone, allowing for any one of these elements to change while still being able to trace a song through time.

One good reason not to catalog songs solely on static lyrics is that many songs had their lyrics ‘cleaned up’ by the time they were properly written down and recorded in the late 19th/early 20th century, sanitizing the liberal use of slurs, stereotypes, and profane and offensive language — perhaps in part due to people like Bildad forbidding them. For example, in yet another version the vulgarity of the lyrics has been toned down considerably, erasing the girls of Booble Alley and replacing them with the slightly tamer instruction for a boy to “kiss the girls” before his lips grow moldy.

When I was a little lad or so my mother told me (Away, haul away…)

That if I didn’t kiss the girls my lips would grow all mouldy (Away, haul away…)

Heaving and Hauling

This very well might have been the song that Melville had in mind as it clearly references Booble Alley in at least some versions. But there’s a significant problem with this theory having to do with the kind of shanty it is. In short, there are two main divisions of sea shanties: “hauling” shanties and “heaving” shanties. Here’s the difference as explained by the Library of Congress in January 2021:

The most basic division was between “hauling” shanties, used for changing the sail configuration or moving other parts of the ship by pulling on ropes, and “heaving” shanties, used for working machines like capstans, windlasses, and pumps. The former typically required individual coordinated bursts of strength when hauling, while the latter required sustained labor while, for example, walking around a capstan for hours in order to raise the anchor.

As you may have guessed, Haul Away Joe/Rosie was a hauling shanty, and more specifically what was known as a halyard shanty (short for ‘haul a yard’). These songs were used, for example, to coordinate raising or lowering heavy sails, and other tasks requiring bursts of heavy labor over a long period of time. The key feature is that pattern of pulling, stopping, breathing, repeating, coordinated by the rhythm of the song.

The problem is that the crew in Moby-Dick aren’t hauling yards while they’re singing about the girls of Booble Alley, or hauling anything at all — they’re at the windlass raising the anchor. From Chapter 22 again:

“Man the capstan! Blood and thunder!—jump!”—was the next command, and the crew sprang for the handspikes. […]

Bildad, I say, might now be seen actively engaged in looking over the bows for the approaching anchor, and at intervals singing what seemed a dismal stave of psalmody, to cheer the hands at the windlass…. […]

At last the anchor was up, the sails were set, and off we glided.

The windlass is in essence a winch, a large drum connected to the anchor ropes which the men slowly turned round and round with wooden “handspikes” sticking out like spokes. The windlass, or “capstan” (there is a technical difference but Melville uses them interchangeably) was also used while “cutting in” to take the blubber off captured whales.

For this work, however, the crew would have used a heaving shanty, sung for more continuous, sustained tasks requiring a steady effort, as opposed to the short bursts associated with hauling shanties. In other words, the men at the capstan weren’t starting and stopping but continuously pushing. It wouldn’t make much sense for the crew of the Pequod to sing a halyard shanty to coordinate the slow, plodding work of turning the windlass.

So, could there be another song that fits the bill? It seemed like a tall order, but what I was looking for was 1) a heaving shanty 2) known to be sung when weighing anchor 3) with a version mentioning the girls of Booble Alley, and 4) is known to be used by about 1840 when Melville went to sea. But was it an impossible task?

Sally ‘Round, Sally Brown

OK so maybe this wasn’t so impossible after all and, as luck would have it, just such a song has already been identified — just seemingly not by Melville scholars. Several shanty enthusiasts, however, immediately recognized it as one called “Sally Brown,” a sort of paean to a mixed-race girl from the West Indies with whom the narrator is in love, but whose mother forbids the relationship.

Sally Brown actually pops up as a character in quite a few shanties (as does just the name Sally, presumably for being an easy rhyme) but in this case the song — and its many obscene verses — is devoted exclusively to her. In fact, most of the verses recorded by Hugill and others in the early 20th century are really too obscene to repeat here. Instead I’ll use an even more sanitized version from a recent book by Karen Dolby, Sea Shanties: The Lyrics and History of Sailor Songs, a book which seems to have cashed in on the inexplicable early pandemic shanty-craze.

I shipped on board of a Liverpool liner

Way-hey, roll and go

And we rolled all night and we rolled all day

For I spent my money along with Sally Brown

Sally lives in old Jamaica (Way-hey, roll and go)

Selling rum and growing tobacco (For I spent my money…)

Sally lives on the old plantation

She is a daughter of the Wild Goose Nation

Seven long years I courted Sally

But all she did was dilly-dally

Sally Brown, what is the matter?

Pretty girl but can't get at her

The sweetest flower in the valley

Is my own, my prettiest Sally

Sally Brown, I love you dearly

You had me heart, or very nearly

Her mother doesn't like a tarry sailor

So I shipped away in a New Bedford whaler

Sally Brown, I long to see you

Sally Brown, I'll not deceive you

This rendition gets the point across and is at least fit for print in the 21st century (take my word for it that you’re better off not looking up more “authentic” versions). Hugill believed that the song actually originated in the West Indies where it continued to be sung by lumberman/log-rollers in port towns into the 20th century. The West Indies were in fact a “breeding ground” of many of the most common shanties, writes Hugill.

[T]he West Indies was undoubtedly a breeding ground of shanties. In the thirties when I gained many ‘new’ shanties from West Indian shantymen it was still possible to hear them being used in places like Tobago, where they hauled sugar boilers ashore by means of tackles through the surf, after they had first been floated shorewards from deep-sea vessels lying in the roadstead. In the West Indies too, particularly in Jamaica, until recent times it was possible to hear shanties sung—such as Sally Brown and its variants—while Negro loggers with peevie and hand-spike rolled the logwood waterwards. ‘Roll de mutu!’ was a common shout heard when singin’ out only.

Of particular interest for our search is that Hugill wrote in his 1961 book Sea Shanties from the Seven Seas that the song was “invariably sung at the capstan.” That’s also where the song is being sung in the first documentation of its usage from nearly 200 years ago: a travelogue published by British naval officer Capt. Frederick Marryat, who became a successful writer of nautical fiction in the 1830s.

In 1837, Marryat traveled from England to America and recorded his thoughts and opinions in his book Diary in America, beginning with the ship leaving from Portsmouth. As the crew raised the anchor at the windlass, Marryat became intrigued by the shanty he heard — a novel experience for him as shanties were “forbidden by the etiquette of a man-of-war” — and describes the scene, interlaced with the song’s lyrics (italics mine):

I was repeating to myself some of the stanzas of Mrs Norton’s “Here’s a Health to the Outward-bound,” when I cast my eyes forward. I could not imagine what the seamen were about; they appeared to be pumping, instead of heaving, at the windlass. I forced my way through the heterogeneous mixture of human beings, animals, and baggage which crowded the decks, and discovered that they were working a patent windlass, by Dobbinson—a very ingenious and superior invention. The seamen, as usual, lightened their labour with the song and chorus, forbidden by the etiquette of a man-of-war. The one they sung was peculiarly musical, although not refined; and the chorus of “Oh! Sally Brown,” was given with great emphasis by the whole crew between every line of the song, sung by an athletic young third mate. I took my seat on the knight-heads—turned my face aft—looked and listened.

“Heave away there, forward.”

“'Aye, aye, sir.”

“‘Sally Brown—oh! my dear Sally.’” (Single voice).

“‘Oh! Sally Brown.’” (Chorus).

“‘Sally Brown, of Buble Al-ly.’” (Single voice)

“‘Oh! Sally Brown.’” (Chorus).

“‘I went to town to get some toddy.’”

“‘Oh! Sally Brown.’”

“‘T’wasn’t fit for any body.””

“‘Oh! Sally Brown.’”

“Out there, and clear away the jib.”

“Aye, aye, sir.” […]

“‘Sally is a bright mulattar.’”

“‘Oh! Sally Brown.’”

“‘Pretty girl, but can’t get at her.’” […]

“‘Seven years I courted Sally.’”

“‘Oh! Sally Brown.’”

“‘Seven more of shilley-shally.’”

… and so on. The scene is remarkably similar to the one in Moby-Dick. Melville was certainly familiar with Marryat, and even name-checks him in Chapter 4 of Typee as a writer who often inspires “long-haired, bare-necked youths” to go to sea. When Melville began publishing his own adventure novels set at sea he was often compared to Marryat, and may have even ‘borrowed’ some elements of Marryat’s The Phantom Ship (1839) for Redburn.

In any case, this video is one of the few that I’ve found which hews pretty closely to what we know of as the original lyrics, and even sung at the windlass (though of a different kind than described by Marryat and Melville).

The difference between the rhythm of this heaving shanty and a hauling/halyard shanty is, well, subtle to my ears, and perhaps rightly so. Stan Hugill even wrote that “The shape of [Sally Brown] is undoubtedly that of a halyard song,” though it is, by all accounts, a capstan shanty. In the same way that shanty lyrics became gradually sanitized, perhaps this is also a product of time. As shanties became increasingly divorced from their use on the ship and reinterpreted as a subgenre of 19th century folk music, they lost a bit of that stomping, task-oriented rhythm.

For example, compare the track above to Paul Clayton’s jauntier 1956 recording of “Sally Brown” from his album “Whaling and Sailing Songs from the Days of Moby Dick.”

This version, as you’ll hear, erases the reference to Booble Alley and aside from the title of the album, the connection to Moby-Dick seems incidental, drawing on the novel more as a framing device than anything. Similarly, Sally Brown also very briefly appears in John Huston’s 1956 film adaptation of the book. David Peloquin, writing in the Leviathan journal on the 60th anniversary of the film’s release, managed to pick out a few notes of “Sally Brown” played on the concertina at the start of the scene at the Spouter-Inn (jump to about 3 minutes and 45 seconds).

The Gals o’ Booble Alley

So can we conclusively say that the crew on the Pequod were singing “Sally Brown” and not “Haul Away Joe”? Of course not. On the one hand, there’s clear evidence in favor of Sally Brown on account of it being a capstan shanty (and against Haul Away Joe, a halyard). On the other, Melville’s phrase “girls in Booble Alley” does seem to be a better match to the “gals of Booble Alley” in Haul Away Joe compared to “Sally Brown of Buble Alley.”

It might also be the case that Melville was familiar with both shanties and conflated them, either intentionally or in error — or that it’s neither one of these songs. It’s certainly possible that Booble Alley appeared as a motif in many more shanties in the early 1840s and, like both Haul Away Joe and Sally Brown, it was erased sometime over the century or so before it was properly recorded.

Nevertheless, if this investigation has appeared anywhere in the Melville academic literature then I’ve apparently missed it. I’m even more surprised at the end of my research than when I started that just one of the major annotated versions mention the possibility that the song was “Haul Away Joe”, and none mention “Sally Brown.” As one of the more unsavory references made in the book, perhaps it was one that had to be cut for space.

But speaking of unsavory, in the next post we’ll dive deeper into “Booble Alley,” not just something Melville heard about in song but a real place in Liverpool visited for himself and wrote about at length.

Hello Adam-- Nice article and the recorded video and audio renditions of the shanties are super. My knowledge of sea shanties has grown immeasurably. I do not have Booble Alley in the Moby-Dick Gazetteer (yet). I think I assumed it was a generic term for red light district or something of the sort, so not mappable to a specific place. If your follow-up article can shed light on its location in Liverpool, then I will add it to the Gazetteer. Cheers- Bill