One thing that makes this blog sustainable is that there’s no shortage of unexpected cultural crossovers where Melville intersects with some of the more unusual parts of the last 100 years. Turn over enough rocks and you’re bound to find some connection, or at least enough to start digging a whale-shaped rabbit hole.

To that effect, I recently came across a question posed to Reddit’s r/AskHistorians community related to a video about the Zodiac Killer, the still unidentified serial killer from the late 1960s:

I am watching a video on the Zodiac Killer and in one of his letters, he mentions a specific pin that was popular around 1969 that said "Melville Eats Blubber" on it. I cannot find WHY these buttons were made but I did find they were originally made by Horatio Button Company. I would have to guess it has to do with Melville's most famous work Moby Dick as it uses the word blubber. Was it because he criticized biblical verses? Can someone help me figure out the reason behind these pins?

Both the button and the Melville connection to the Zodiac Killer were new to me, and just the right kind of bizarre that piques my interest. The person who submitted the question even did a bit of the legwork. And so I fell in immediately.

Melville Ate Blubber?

First, let’s address the whale in the room: did Melville actually eat blubber? Well, it’s certainly not unimaginable that he tried it. After all, Chapter 65 of Moby-Dick is entirely focused on “The Whale as a Dish,” including the history and relative merits of consuming its various parts. On the whole, Ishmael muses, the world might be more inclined to eat whales “were there not so much of him; but when you come to sit down before a meat-pie nearly one hundred feet long, it takes away your appetite.”

In terms of eating blubber, the thick layer of fat that keeps whales warm, Ishmael mostly sticks to cultural and historical examples. For instance, he writes that it’s particularly prized by the “Esquimaux” (now more appropriately called Canadian Inuit), and mentions an incident in which a group of Englishmen were stranded by their whaling ship in Greenland and survived by eating scraps of fried blubber.

Only the most unprejudiced of men like Stubb, nowadays partake of cooked whales; but the Esquimaux are not so fastidious. We all know how they live upon whales, and have rare old vintages of prime old train oil. Zogranda, one of their most famous doctors, recommends strips of blubber for infants, as being exceedingly juicy and nourishing. And this reminds me that certain Englishmen, who long ago were accidentally left in Greenland by a whaling vessel—that these men actually lived for several months on the mouldy scraps of whales which had been left ashore after trying out the blubber. Among the Dutch whalemen these scraps are called “fritters”; which, indeed, they greatly resemble, being brown and crisp, and smelling something like old Amsterdam housewives’ dough-nuts or oly-cooks, when fresh.

As noted in several annotated editions, Dr. “Zogranda” is one of the many nicknames that Melville used for Captain William Scoresby, an English whaler and arctic explorer. Melville cribs from Scoresby’s work throughout Moby-Dick, but nevertheless enjoyed lightly mocking him; elsewhere in the book, he’s referred to as “Snoghead” and “Fogo Von Slack.”

In fact, Scoresby appears to be the source for all of Melville’s information in this paragraph. In his 1820 book An Account of the Arctic Regions, for instance, Scoresby suggests that Esquimaux eat blubber and “give it as food to their infants, who suck it with apparent delight.” The story about the stranded Englishmen, meanwhile, is taken from Scoresby’s 1799 book, The Northern Fishery:

These men, like the former, were abandoned to their fate; for on proceeding to the usual places of resort and rendezvous, they perceived with horror that their own, together with all the other fishing-ships, had departed. By means of the provisions procured by hunting, the fritters of the whale left in boiling the blubber, and the accidental supplies of bears, foxes, seals, and sea-horses… they were enabled not only to support life, but even to maintain their health little impaired, until the arrival of the fleet in the following year.

Melville’s only comment about eating blubber that seems to come from his own experience is the line that comes just after the excerpt above, noting that these blubber fritters look like Dutch olykoeks and “have such an eatable look that the most self-denying stranger can hardly keep his hands off.” And he isn’t wrong, to be honest.

We might also consider the letter that Melville wrote to Richard Henry Dana Jr. as he worked on Moby-Dick, in which he seems to suggest that one might eat blubber as long as it’s seasoned well:

It will be a strange sort of a book, tho’, I fear; blubber is blubber you know; tho’ you may get oil out of it, the poetry runs as hard as sap from a frozen maple tree;—& to cook the thing up, one must needs throw in a little fancy…

To me, this sounds like a comment made by someone who has some experience preparing and putting down some fritters. But this is probably as close as we’re going to get in determining whether Melville really was a blubber eater.

Pushing Buttons

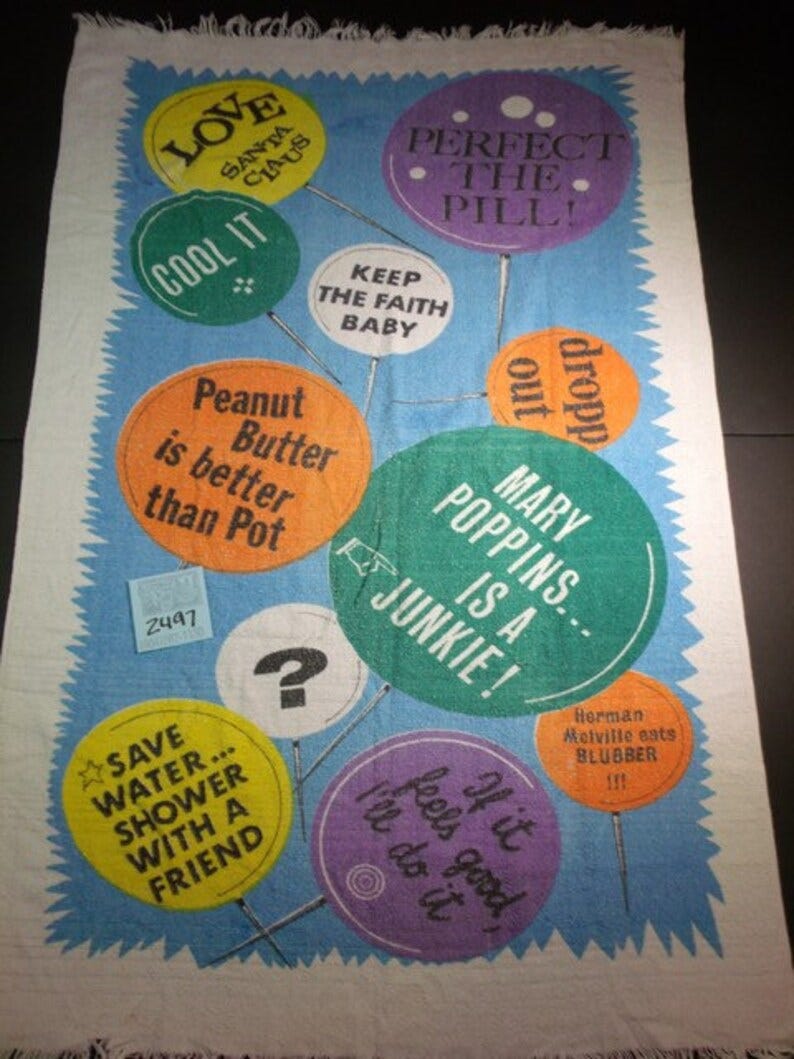

Returning to the original question, it’s easy enough to find images of the buttons, which seem to have come in at least two variations. One with blue text on black reading “MELVILLE EATS BLUBBER;” the other with purple text on white and which adds his first name, reading “HERMAN MELVILLE EATS BLUBBER.”

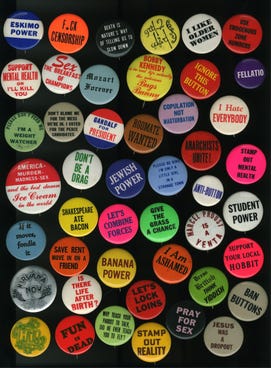

As suggested in the question, MELVILLE EATS BLUBBER was one of many buttons created by a man named Irwin Weisfeld beginning around 1966, many of which were jokes about politics, sex, art, philosophy, or just general observational or abstract humor. Melville certainly wasn’t the only literary target, though. The Melville button was apparently “something of a sequel” to an earlier button, SHAKESPEARE EATS BACON — presumably a reference to the theory that Francis Bacon was the true author of Shakespeare’s plays. There were also buttons like MARCEL PROUST IS A YENTA (I guess “Proust eats Madeleines” was too obvious), and several inspired by Lord of the Rings like GANDALF FOR PRESIDENT and SUPPORT YOUR LOCAL HOBBIT.

Now, pardon the detour, but the buttons aren’t even what Irwin Weisfeld is really notable for. Before the buttons came along, Weisfeld was the owner of The Bookcase, a bookshop in midtown Manhattan which found its way into the history books in September 1963 after a clerk sold an “obscene” novel to a 16-year-old girl. The book in question was Fanny Hill (more properly titled “Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure”), an erotic novel by John Cleland considered to be "the first original English prose pornography, and the first pornography to use the form of the novel."

As you’ll note from the cover of the then recently-published 1963 edition, the book originally came out in 1749, more than two hundred years before the illegal sale. And though there have been several editions with extensive illustrations (I’d even advise caution in opening the book’s Wikipedia page in mixed company), this particular edition by Putnam was completely unadorned with any images.

Nevertheless, the girl’s mother filed a criminal complaint and both Weisfeld and the clerk who sold the book were charged with violating State Penal Law 484-H, which prohibited knowingly selling material which "exploits, is devoted to, or is primarily made up of of descriptions of illicit sex, or sexual immorality" to anyone under 18 years old.

Admittedly, the book unequivocally fits this description and thus the sale to a 16-year-old did technically break the law. Weisfeld briefly tried to argue that he couldn’t possibly know the content of all 30,000 books in his store but this was even less convincing. Not only was this particular book very well-known at the time for its racy content, during the trial it was revealed that the girl found it below a sign which loudly announced its controversial history:

"WHY KID AROUND? The pile of books below entitled "Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure" is in reality the long banned (over 100 years) FANNY HILL which is now, in the new era of Publishing and Reading Freedom, at last available to this generation, as it was not to any other generation of Americans.”

But something even more important came to light during the trial: the entire incident was a set-up, orchestrated by the religious right organization Operation Yorkville. The group regularly used the court system to ban books, art, and other media which they deemed obscene, and weaponizing ambiguous laws to scare booksellers from stocking books that could get them wrapped up in legal trouble. The girl, of course, never read the book; it was handed directly to Operation Yorkville operatives who gave it to authorities, which in turn charged Weisfeld at their behest.

(As an aside, Operation Yorkville later became known as Morality in Media and more recently changed its name again to the more benign-sounding National Center on Sexual Exploitation, though it still focuses its energy fighting pornography, same-sex marriage, sex education, and the like.)

Weisfeld, represented by the ACLU, changed tactics and argued in front of a panel of three judges that the law was unconstitutional, just as many others had before him who found themselves in similar predicaments. In truth, his plight was actually just the latest skirmish in the long mid-century war over first amendment rights, one in which publishers and bookstores regularly found themselves on trial for selling books like Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley's Lover, and Joyce’s Ulysses.

Nevertheless, despite the fact that just a few months earlier the New York State Supreme Court ruled that Fanny Hill was not obscene, both Weisfeld and the clerk were convicted. The court reasoned that the State Supreme Court ruling applied only to adults, and that it was a separate matter to prohibit the sale of such books to minors. Weisfeld was sentenced to “30 days in the workhouse” plus a $500 fine. The clerk received 10 days in the workhouse.

Long story (a bit) shorter, Weisfeld and the clerk immediately appealed with financial assistance from Barney Rosset, owner of the Grove Press publishing house and staunch defender of first amendment rights. In July 1964, the New York State Court of Appeals overturned Wesifeld’s and the clerk’s convictions and ruled that the law was unconstitutional. Judge Francis Bergan wrote for the majority opinion:

“The suppression of a book requires not only an expression of judgment by the court that it is so bad, in the view of the judges, that it is offensive to community standards of decency as the Legislature has laid down; but also that it is so bad that the constitutional freedom to print has been lost because of what the book contains. The history and tradition of our institutions stand against the suppression of books.”

But Weisfeld still wasn’t done. In 1965, the state legislature rewrote the section of the law in a way that continued to allow book bans based on age, and so once again he sued and took the case to the State Court of Appeals. Again, he argued that even these restrictions violated the first amendment. But he’d gone a step too far; the court upheld the constitutional grounds of restricting books and other material based on age.

Although this was the end of the line for Weisfeld, it wasn’t the end for challenges to Fanny Hill elsewhere. In 1964, a Massachusetts Superior Court judge ruled that the book was obscene and “not entitled to constitutional protection,” and Putnam took the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. There, the judges rebuffed the attempt, holding that the book was not "utterly without redeeming social value,” and that “books could not be deemed obscene unless they were unqualifiedly worthless, even if the books possessed prurient appeal and were ‘patently offensive.’” (You can actually listen to the Supreme Court’s oral arguments from 1965 on Oyez.com).

American publishers and booksellers had punched back, but the war on obscenity would march on well into the 1970s and 80s with many more Supreme Court cases and two separate presidential commissions to look into the issue of pornography and obscenity.

Meanwhile, Irwin Weisfeld had another idea up his sleeve — or perhaps affixed to it.

IGNORE THIS BUTTON

So where were we? Ah, yes. Irreverent buttons. At the end of his court battles, Weisfeld ultimately chose to close his bookstore and was understandably looking for some additional income. A friend suggested that he find a way to capitalize on his quick wit and biting sense of humor, and in 1966 — no doubt influenced by the button-crazy world of political campaigns of the era — Weisfeld founded the Horatio Button Company, named after his three-year old son.

As you may be able to make out above, some of the many phrases he turned into buttons included ANARCHISTS UNITE, JESUS WAS A DROPOUT, NIRVANA NOW, KILL FOR PEACE and, my personal favorite, WHERE IS LEE HARVEY OSWALD NOW THAT WE REALLY NEED HIM? From what I can tell, the output was a mix of Weisfeld’s own ideas as well as others already floating around in the ether — whether written on bathroom stalls, paraded on protest signs, or etched into high school desks.

Weisfeld printed the buttons himself, advertising them in magazines and shipping them from an office in Manhattan. To be clear, Weisfeld was just one of many manufacturers of such buttons, but these proto-memes spread quickly in youth and counter-culture circles. In March 1968, the Cincinnati Enquirer declared that “One of the newest fads among teens is buttons with kooky sayings. Pin them on your shirt, blouse, or coat, anywhere people will notice.”

Robert Reisner, author of a 1971 book about the history of graffiti, even remarked on the button fad as simply a modern form of the act. He recalled that “button madness was full upon us in 1966-68” and compared the fad to, of all things, “sex novels that would bore the Marquis de Sade into celibacy.” (I wonder which ones he had in mind…)

Any overview of the why, what, and who of graffiti must include comment on a commercial but nonetheless, I feel, honest extension of the graffiti concept as it is conceived today. And that's the button. Buttons, those dollar-sized, plastic-protected stickpin legends, have become so universal that one can almost say "Button, button, just who doesn't have a button?" I refer to them as "walking graffiti." […]

They invite comment and debate and, as such, are a means of getting acquainted. I, for one, feel you have the right to stop anyone wearing a button and ask about it. He or she will almost always respond in a friendly way, since a basic purpose of the button is to draw attention to the wearer as well as to his point of view. […]

A great deal of button-wearing is not necessarily for espousal of a cause but merely because it is the "in" thing. We are a nation willing to buy anything that we are told is "hip"—hula hoops, mini skirts, maxi coats, pop posters, sick greeting cards, nonfunny nonbooks, sex novels that would bore the Marquis de Sade into celibacy.

Every man wants to be a comic, and when a person buys a funny button, it's as if he had made up the saying. It's his discovery, despite the fact that the item is selling in the tens of thousands.

All this to say that MELVILLE EATS BLUBBER was one of Weisfeld’s many creations and it, too, joined the button/graffiti/bumper sticker circuit. Per the Los Angeles Times, former reporter Wolf Larson spotted in a Death Valley gas station bathroom around 1967-68:

It also appeared on a 1960s button-themed beach towel:

… and a cartoon in The Saturday Review in 1968:

I can't say how much money Weisfeld made from selling the buttons or if in their own ironic way they helped pay for his obscenity trials, but tragically he died just a few years later in September 1968 at just 36 years old, attributed to heart failure. Just a year later, Weisfeld’s experience being convicted for selling Fanny Hill was turned into a book by Irving Wallace titled The Seven Minutes, which was then adapted into a film of the same title. And his son Horatio "Ray" Weisfeld, for whom the button company was named, grew up to be a comic book artist and publisher, often pushing the limits of obscenity himself in magazines such as Penthouse Comics, an off-shoot of Penthouse Magazine.

The Zodiac Demands a Button

Of all the buttons Weisfeld created, though, MELVILLE EATS BLUBBER undoubtedly had one of the more bizarre afterlives.

Just to briefly set the scene, the serial murders attributed to the Zodiac Killer began in December 1968 and continued through at least October 1969, spread throughout the San Francisco Bay Area. After each of the murders — and for several years after the last confirmed murder — the Zodiac made contact with the police and local media through phone calls and letters, supposedly offering clues to his identity via cryptograms and generally taunting investigators.

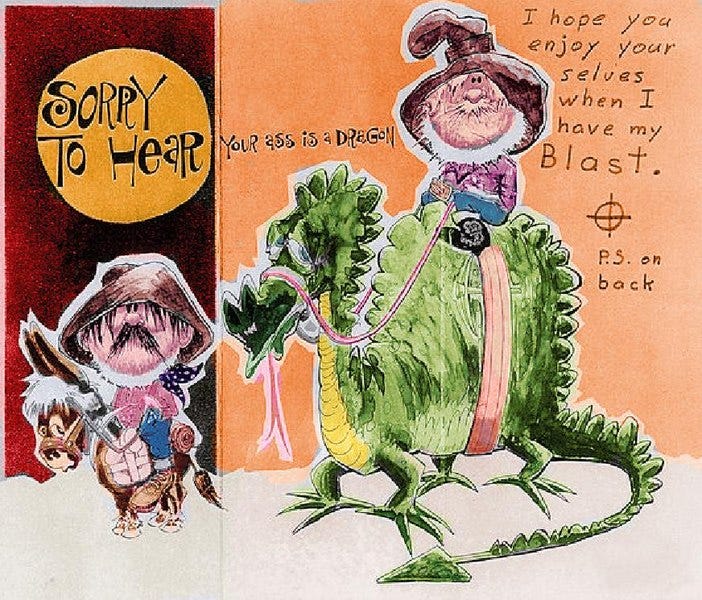

On April 28, 1970, the Zodiac sent one of these cryptic and threatening letters to the San Francisco Chronicle, written on the back of a greeting card featuring a play on Don Quixote who rides a dragon beside Sancho Panza and his donkey.

In the message on the back of the card, the Zodiac makes two demands. First is that the newspaper must publish details about a bomb he had previously threatened to detonate on a bus. Pretty normal serial killer stuff. Second… well, he wanted people to wear a Zodiac-themed button like the ones he’s seen around town such as “black power” and “melvin eats bluber.”

I would like to see some nice Zodiac butons wandering about town. Every one else has these buttons like [peace sign], black power, melvin eats bluber, etc. Well it would cheer me up considerably if I saw a lot of people wearing my buton. Please no nasty ones like melvin’s. [note: errors in original]

The letter doesn’t actually say “Melville Eats Blubber,” as the Reddit user mentioned. Rather, he cites a button reading “Melvin Eats Blubber,” though it’s clearly a reference to Weisfeld’s button. Among Zodiac fanatics, it’s presumed that “Melvin” was a reference to Melvin Belli, a famous celebrity attorney who represented clients such as Zsa Zsa Gabor, Errol Flynn, Chuck Berry, Muhammad Ali, The Rolling Stones, Mae West, and Jack Ruby. About six months earlier, in October 1969, Belli had inadvertently become part of the Zodiac case — or at least a sideshow thereof — when someone claiming to be the Zodiac called the Oakland Police Department to say that he would call into a local radio show and provide information but only if either Belli or criminal defense attorney F. Lee Bailey were also present.

Belli agreed to be part of the stunt and the station soon received several calls from someone claiming to be the Zodiac killer. Belli and the radio host pleaded with him to stop the murders and come forward, but man on the line only said that he couldn’t; he was afraid that he would receive the death penalty. The call was later traced back to a mental patient in an Oakland hospital, and police determined he was not the Zodiac after all.

Belli nevertheless received a letter from the real Zodiac Killer a few months later in December 1969, in which he wished Belli a “happy Christmass” and asked for help before he lost control and murdered again. The letter also contained a piece of a shirt taken from known Zodiac victim Paul Stine, proving that this time he was the real deal. Not to get too deep into the Zodiac investigation lore, but the April 1970 letter (the one referencing to the Melville button) is also interesting in that it was written on a greeting card printed by a company called Jolly Roger Cards. This may have been a particularly perceptive reference to Belli. Apparently, when Belli won a case, he would fire a small cannon from his office window while raising the Jolly Roger flag. But then, maybe it was just another strange coincidence.

Remarkably, on June 26, 1970, the Zodiac followed up about the buttons, peevishly complaining to the San Francisco Chronicle in another letter that he was “very upset” that the people of the Bay Area “have not complied with my wishes for them to wear some nice [zodiac] buttons.”

He followed up again in July 1970, upset that “you people will not wear some nice [zodiac] buttons,” and threatened to harm more people as a result.

What’s really crazy about this is that throughout his murder spree and ongoing antagonization of the police — which again went on for years — the Zodiac only ever made two demands: first, that newspapers print the details of his crimes; and second, that people to wear his “nice zodiac buttons.” I mean, the guy really loved these buttons.

Weisfeld had already been dead for two years by the time of the first letter mentioning buttons, so we can only wonder what he would have made of the bizarre situation, but it seems Zodiac buttons never did catch on. It’s also unclear whether the Zodiac really did murder more people after the buttons failed to materialize, though there are many possible/suspected victims.

There was one Zodiac-related button that did get made, however. In October 1970, reporter Paul Avery of the San Francisco Chronicle, who reported on some of the murders, received his own Halloween-themed letter from the Zodiac. The card seemed to threaten his life, reading in part: “Peek-A-Boo / You Are Doomed!”

Avery told the press he wasn’t scared, but he nonetheless started carrying a gun in his jacket. And as a precaution for him and everyone around him, one of his colleagues had printed — what else — hundreds of buttons for the paper’s staff to wear reading: “I AM NOT AVERY.”

A Social Disease?

Finally, one thing I tried — but failed — to figure out, was whether Weisfeld was also the creator of another Melville-inspired joke that seemed to go “viral” around the same time: MOBY DICK IS NOT A SOCIAL DISEASE. (Social disease here meaning an STI). In fact of the two, I found that this one had more staying power through the decades. If there’s one universal truth through the ages, it’s that the world can’t resist a dick joke — that blubber-eating Herman Melville included. You could, of course, find it on a button:

Or on a bathroom wall:

A cheeky professor at Penn State University used the eye-catching phrase in the school newspaper to promote an upcoming talk about disability and rehabilitation.

The phrase even made it into the 1978 Burt Reynolds film The End, in a line delivered by a crazed Dom DeLuise as a mental patient explaining why he murdered his father. (At 59:30: “He was so stupid! He said how he thought that Moby Dick was a venereal disease!”)

I tried multiple times to get in touch with Ray Weisfeld to ask him about his father, but never heard back. That said, it’s unlikely whether he, or anyone, knows anymore which jokes and phrases came from Irwin and which just appeared one day on a bathroom stall.

References

Reddit thread with the original question and answers

Robert George Reisner, Graffiti: Two Thousand Years of Wall Writing, 1971

“Irwin Weisfeld,” Wikipedia (“Talk” page, for source about Weisfeld’s friendship with his professor, Martha Foley)

“The Zodiac Button,” Heavy Metal Magazine, January 2012

What a fun lot of research. And btw the read aloud group in Melbourne came upon “All visible objects” a couple of weeks ago in our read of chapter 36!