EXTRACTS: Ambrotype Epilogues

; or, on misplaced Melville mementos and a goose-eye view of Boston

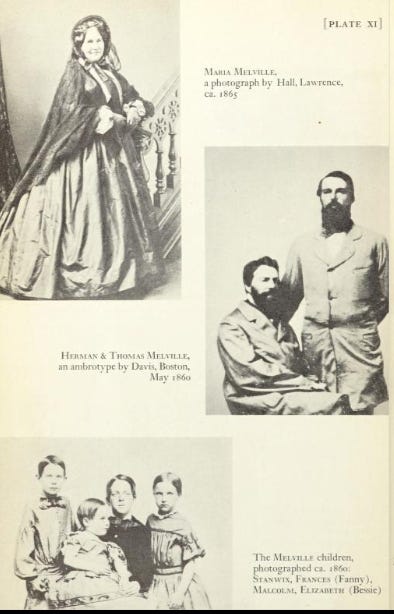

Following last week’s post, here are a few stray notes related to the ambrotype of Melville and his brother Thomas from May 1860.

Another missing Melville photograph?

It’s one thing when some artifact from the mid-19th century just didn’t survive the years and has never been seen. Take, for example, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s replies to Melville’s letters, the original manuscript for Moby-Dick, or the (possible) daguerreotype of Melville taken by photographer Samuel Lyon Walker in 1847. It’s another thing entirely when something did survive, was known to mid-20th century scholars, and only then disappeared. It’s mismanagement of the highest order.

In 1967, Melville scholar Morris Star published an article in the Bulletin of the New York Public Library titled “A Checklist of Portraits of Herman Melville,” in which he created an enumerated list of every known photograph, portrait, and print and any copies/replicas made at the time. Interestingly, Star’s list includes two distinct entries for the May 1860 ambrotype, each with different dimensions. One of them he says was held at the Berkshire Athenaeum, the other at Harvard’s Houghton Library.

If you watched the video I linked to in the previous post, you’ll recall that ambrotypes were made by what’s called the “wet collodion process.” This process could produce a photo negative and thereby enable limitless copies. But it could also be used to print a positive directly on glass called an ambrotype. In other words, these were one-and-done.

All this to say that item 4 on Star’s checklist, “Another Ambrotype,” was an original ambrotype photo on glass — not simply a copy. For both photos, he references plate XI in Jay Leyda’s The Melville Log. Here’s what that page of Leyda’s book looks like, showing a single photo for both:

The more I learned about the photographer, Philemon Davis, the more this made sense. Starting in 1856, Davis began advertising what he called a “double camera,” writing in the Boston Herald on November 24, 1856 that it made “two correct Daguerreotypes or Ambrotypees of every person who looks at it.”

That Double Camera owned by Davis & Co., at the corner of Winter and Washington streets, is a perfect wonder in the Daguerrean art. It makes two correct Daguerreotypes or Ambrotypees of every person who looks at it, and the price for taking a peep at this wonderful instrument is 25 cents. If there is a person who has not seen the Double Camera we would advise them to visit Davis & Co.’s rooms, corner Winter and Washington streets.

In another ad, Davis claimed to hold the patent on the double camera and that it was the only one in New England — or, he immediately hedged, “that ever has been in use by any concern.”

Patent Double Camera, This is the only Double Camera in New England! Or that ever has been in use by any concern. We have the Exclusive Right To Use It, and do not make our patrons think its double or triple by inserting False Tubes, but we do take, in reality, two perfect pictures at one sitting. This is no child’s story, but is a matter of fact which may be tested by the customer who has the privilege of seeing both pictures. The Double Camera is by far The Highest Point Attained as yet in this department.

In other words, it makes perfect sense that there would be two ambrotypes from Herman and Tom’s visit in May 1860. That second photo, however, is now apparently missing.

When I initially came across Star’s checklist, I searched Harvard’s library catalog for any record of the ambrotype and saw nothing matching the description. Nor could the librarian staffing their library chat window, who passed it onto the reference librarian, who passed it onto their photograph librarian, who passed it onto the associate curator of the collection. None of them could find the photo. Last week, I followed up again to ask if they could check the original accession inventory from whenever the received the Melville collection if only to confirm that this wasn’t something Star listed in error somehow, but as of this post I haven’t heard back yet.

Partial as I am to recovering missing Melville artifacts, this one I might not exactly pursue to the ends of the earth. Given what Davis says about his double camera, and the fact that Star doesn’t provide any additional description of the photo, all signs point to it being essentially the exact photograph we already have of Herman and Thomas. It’s tragic that it might be lost, but at least we know exactly what it would have looked like.

That said, of course I’ll be following up with the Houghton Library to see what else we can learn about its existence and disappearance.

Wait, and ANOTHER one?

The ambrotype isn’t the only thing from 1860 that disappeared sometime in the 20th century, though this one is even more galling.

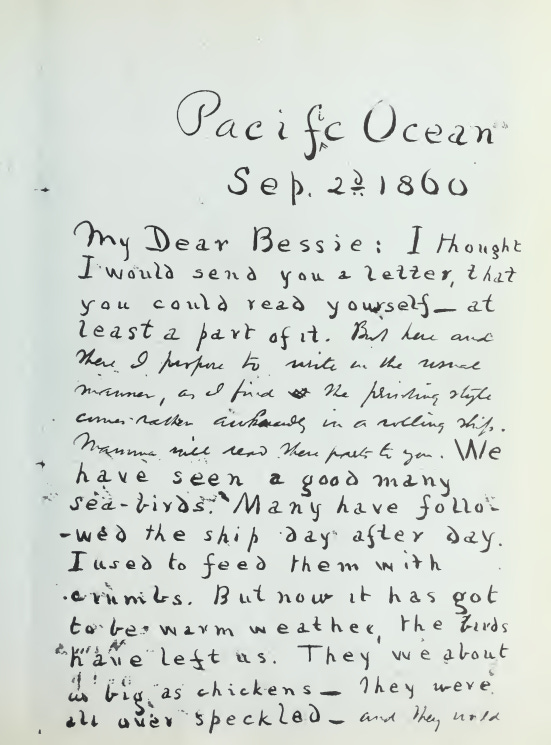

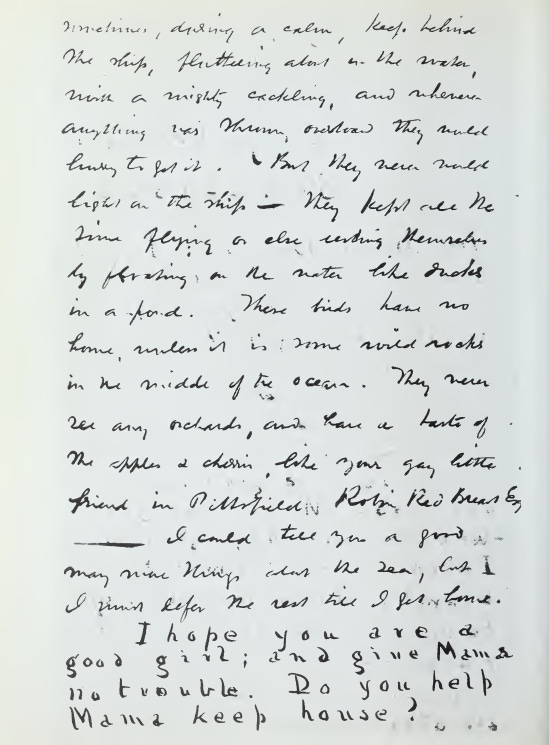

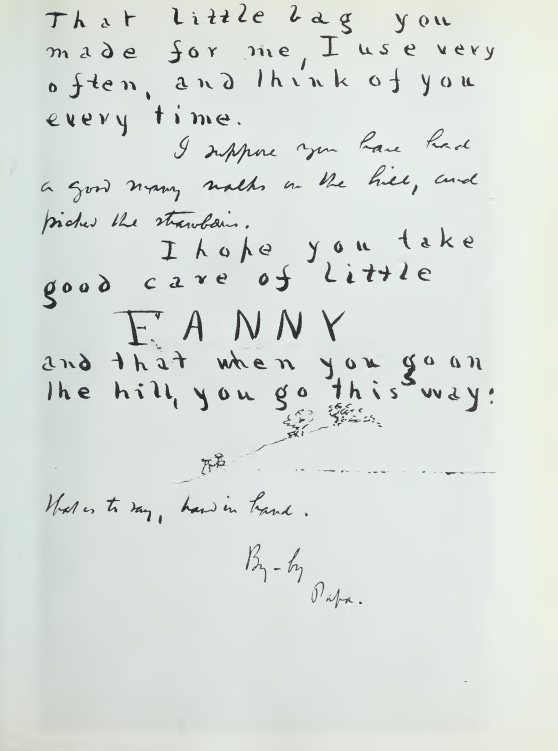

When Herman was aboard the Meteor with his brother Tom, he wrote several letters addressed to his young children. The one, for example, from September 2, 1860, is addressed to his then-seven year old daughter Bessie, telling her about the birds he was seeing, instructing her to behave, and even including a little drawing of how she was to hold her little sister’s hand when they went up the hill. They’re very cute, even the shifts in his handwriting are insane.

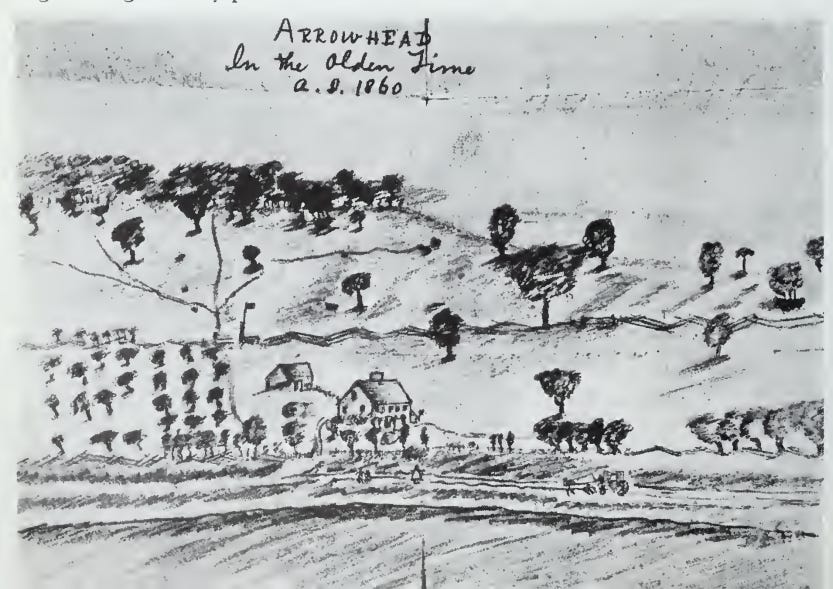

Another one of these letters, to his son Malcolm, included a drawing he made of Arrowhead. He wrote that the carriage on the bottom right was meant to depict him on his return to the farm with his family waiting to greet him.

Drew this at sea one afternoon on deck — & then in the calm. Made me feel as if I was there, almost — — such is the magic power of a find Artist. — — Be it known I pride myself particularly upon “Charlie” & the driver. — It is to be supposed that I am in the carriage; & the figures are welcoming me.

Appallingly, this drawing is now missing, either taken or misplaced by Raymond Weaver, Melville’s first biographer. An explanation is given in the Northwestern-Newberry edition of his journals:

The original drawing and accompanying note, now lost, were lent by Eleanor Melville Metcalf to Raymond Weaver for reproduction in his biography and were not returned to her. See his Herman Melville: Mystic and Mariner (New York: Doran, 1921), where each is separately shown on the plate facing p. 368. There the drawing (10.1 x 7.3 cm) is placed above, with the caption "MELVILLE AS ARTIST" and the note (6.8 x 5.5 cm) below, uncaptioned. No further information is given on the plate or in the text. Study of Weaver's two reproductions shows that Melville made both the drawing (in pencil, with the heading possibly in ink) and the note (possibly in ink) on paper manufactured with lines… The original dimensions of both items remain conjectural, but to judge from the narrow .5 cm line intervals in Weaver's reproductions compared to the . 8 cm ones in the paper of his 1860 journal and of page 7 of his letter to Malcolm, both were probably nearly two-thirds (60 percent) larger than shown on the plate. Both reproductions were obviously cropped: Melville is unlikely to have left no margins on his drawing or to have executed it— or his note— on the small scale shown (see, for example, how tiny the horse, carriage, and figures still are in the enlarged reproduction here).

In 2011, biographer Hershel Parker wrote on his blog that he made it a habit to buy copies of Weaver’s 1921 Melville biography whenever he saw one for sale, just in case the map is tucked away in the pages there. So far, nothing has come of the efforts and expense.

A Most Curious Intersection

Lastly, an odd coincidence about the ambrotype(s) that I had to mention briefly.

While I was looking for images of the corner of Winter and Washington streets to show the environs of Davis & Co. in May 1860, I came across a photo of the intersection captured in living color… well, in black and white, anyway. The photo was taken in October 1860, just as the brothers were sailing into San Francisco, made by James Wallace Black in a hot air balloon. In fact, it was the first-ever aerial photograph made in America, and the oldest photo of its kind that survives.

Look for the old Trinity Church toward the bottom-right of the photo (later burned in the Great Boston Fire of 1872). The corner of Winter and Washington is just west of that block toward the bottom left of the photo.

In a bizarre coincidence, Melville has yet another connection to the photo. In 1863, it caught the attention of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Melville’s neighbor in Pittsfield and a party to the famous picnic hike where Melville met Nathaniel Hawthorne. Thirty years earlier, Holmes had also written a poem about Herman and Tom’s grandfather, Major Thomas Melvill, presumably for whom Tom was named.

When Holmes saw the aerial view, he remarked that:

"Boston, as the eagle and wild goose see it, is a very different object from the same place as the solid citizen looks up at its eaves and chimneys… Milk Street [left center] winds as if the old cowpath which gave it a name had been followed by the builders of its commercial palaces. Windows, chimneys, and skylights attract the eye in the central parts of the view, exquisitely defined, bewildering in numbers... As a first attempt [at aerial photography] it is on the whole a remarkable success; but its greatest interest is in showing what we may hope to see accomplished in the same direction."

Since then, the historic photograph has been known as “Boston, as the Eagle and the Wild Goose See It” as named by Melville’s friend and neighbor. Small world, looking even smaller by hot air balloon — or wild goose.

I'm now completely caught up with your blog. Really good stuff! What Melville work would you recommend as highest-priority reading after Moby Dick?