Images of Melville, Part 2

; or, on ambrotypes and being oblivionated

Note: I’ll be at the Melville Society Conference at UConn this week. Feel free to say hello if you’re attending! — Adam

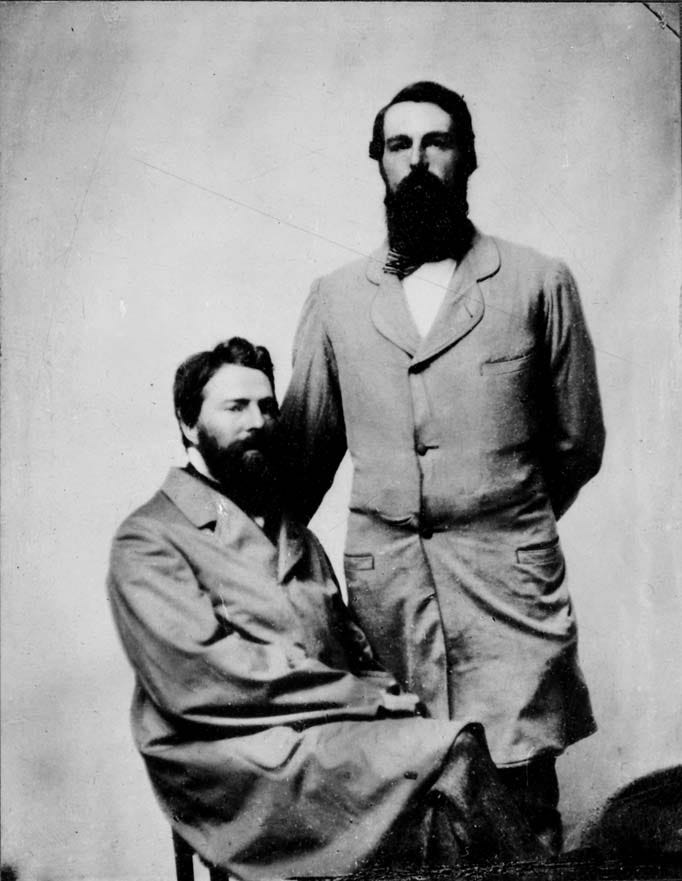

Continuing on the series started a few weeks ago, today we’ll look at the second known image of Melville, an ambrotype from May 1860. The image, taken at a consequential turning point in his life, captures the moment where Melville the swashbuckler, the author, the legend was transmuted into Melville the blue collar customs agent, the domestic poet, the forgotten. But first, a little background.

“To the devil with you and your Daguerreotype!”

In the early months of 1851, Melville had all but locked himself in his study to complete The Whale, which had exploded from prosaic adventure story to a conscious attempt at establishing a high water mark for American literature. By his own admission, he’d churned out Redburn (1849) and White-Jacket (1850) with little gratification, calling them “two jobs, which I have done for money—being forced to it, as other men are to sawing wood.” The Whale, written in the wake of meeting Hawthorne (in person) in August 1850 and Shakespeare (in print) that winter, found him “in a sort of mesmeric state” secluded in his study with his manuscript.

To the annoyance of everyone around him, though, he could be bothered with no other trifles. He’d already skipped Thanksgiving with his in-laws in Boston, and to hear her tell it had practically shoved his mother out of a moving carriage at the train depot to get back to his work. "Herman I hope returned home safe after dumping me & my trunks out so unceremoniously at the depot. Although we were there more than an hour before the train, he hurried off as if his life depended upon his speed; a more ungallant man it would be difficult to find.”

But even at a moment in which it could have really benefitted him to think about the release and publicity of his new book, he stood his ground on one particular bugbear: he would not have his daguerreotype taken, no matter the opportunity. One such request came from Evert Duyckinck, his friend and unofficial dean of the New York literati, who asked Melville in February 1850 if he would care to contribute to his new literary magazine that spring. Duyckinck requested also that he send a daguerreotype, intending to honor Melville in a series of profiles of “Distinguished Americans.”

Melville replied with his regrets that he was “not in the humor” to write for the magazine, and further that he had no daguerreotype to submit. Nor would he send one even if he did. Although he admitted to being “as vain a man as ever lived,” the very idea of photography appalled him. The new technology, he argued, had cheapened portraiture as a distinction among the deserving few. Now, to have ones “mug” in a magazine was now “presumptive evidence that he’s a nobody.”

As for the Daguerreotype (I spell the word right from your sheet) that’s what I can not send you, because I have none. And if I had, I would not send it for such a purpose, even to you.—Pshaw! you cry—& so cry I.—“This is intensified vanity, not true modesty or anything of that sort!”—Again, I say so too. But if it be so, how can I help it. The fact is, almost everybody is having his “mug” engraved nowadays; so that this test of distinction is getting to be reversed; and therefore, to see one’s “mug” in a magazine, is presumptive evidence that he’s a nobody. So being as vain a man as ever lived; & beleiving that my illustrious name is famous throughout the world

Melville ended by saying he would “respectfully decline being oblivionated” by a daguerreotype, a “devel of an unspellable word.” (Can’t argue with him there)

A second request for a daguerrotype came around the same time from International Monthly Magazine. Again, Melville declined, against the wishes of his mother who warned he would appear “strangely stiff” among his contemporaries, all of whom who were having their mugs printed up. Ultimately, neither magazine ran their proposed profiles on Melville, with or without his photo.

Melville satirized these apparently presumptions demands in his next book, Pierre, in which a “literary acquaintance” tries to literally drag the protagonist into a daguerreotype shop by the arm. After a scuffle in the street, Pierre finally shouts at him: “To the devil with you and your Daguerreotype!”

Upon one occasion, happening suddenly to encounter a literary acquaintance—a joint editor of the “Captain Kidd Monthly”—who suddenly popped upon him round a corner, Pierre was startled by a rapid—“Good-morning, good-morning;—just the man I wanted:—come, step round now with me, and have your Daguerreotype taken;—get it engraved then in no time;—want it for the next issue.”

So saying, this chief mate of Captain Kidd seized Pierre’s arm, and in the most vigorous manner was walking him off, like an officer a pickpocket, when Pierre civilly said—“Pray, sir, hold, if you please, I shall do no such thing.”—“Pooh, pooh—must have it—public property—come along—only a door or two now.”—“Public property!” rejoined Pierre, “that may do very well for the ‘Captain Kidd Monthly;’—it’s very Captain Kiddish to say so. But I beg to repeat that I do not intend to accede.”—“Don’t? Really?” cried the other, amazedly staring Pierre full in the countenance;—“why bless your soul, my portrait is published—long ago published!”—“Can’t help that, sir”—said Pierre. “Oh! come along, come along,” and the chief mate seized him again with the most uncompunctious familiarity by the arm. Though the sweetest-tempered youth in the world when but decently treated, Pierre had an ugly devil in him sometimes, very apt to be evoked by the personal profaneness of gentlemen of the Captain Kidd school of literature. “Look you, my good fellow,” said he, submitting to his impartial inspection a determinately double fist,—“drop my arm now—or I’ll drop you. To the devil with you and your Daguerreotype!”

Pierre, a frequent surrogate for Melville’s frustrations as an author, grumbles to himself that whereas a portrait once ‘immortalized a genius’ it now — coining a word — only “dayalized a dunce”.

For he considered with what infinite readiness now, the most faithful portrait of any one could be taken by the Daguerreotype, whereas in former times a faithful portrait was only within the power of the moneyed, or mental aristocrats of the earth. How natural then the inference, that instead, as in old times, immortalizing a genius, a portrait now only dayalized a dunce. Besides, when every body has his portrait published, true distinction lies in not having yours published at all. For if you are published along with Tom, Dick, and Harry, and wear a coat of their cut, how then are you distinct from Tom, Dick, and Harry? Therefore, even so miserable a motive as downright personal vanity helped to operate in this matter with Pierre.

Melville never did get his daguerreotype taken that decade, or anytime during his career as a novelist or short story writer. It was only once he’d given up, finally “oblivionated,” that Melville acceded.

May 1860 — Ambrotype by Davis & Co., Boston

All this preamble brings us to the second surviving image of Herman Melville, a 3 ½” x 2 ½” ambrotype from May 1860 of him and his younger brother Thomas.

We’ll get more into the photo and what an ambrotype is in a bit, but first let’s quickly jump ahead to this momentous point in Melville’s life.

Following the commercial failures of Moby-Dick and Pierre, Melville pivoted to short stories, publishing fourteen of them in the mid-1850s. Despite his dwindling reputation as a novelist, he was apparently still held in high enough esteem to command a high rate per page and was writing as furiously as ever. From this period, of course, came stories like “Bartleby, the Scrivener,” “Benito Cereno,” and a personal favorite, “Cock-A-Doodle-Doo!,” in which Melville rants about yet another rotten technological advancement of the day: trains.

Great improvements of the age! What! to call the facilitation of death and murder an improvement! Who wants to travel so fast? My grandfather did not, and he was no fool. Hark! here comes that old dragon again—that gigantic gadfly of a Moloch—snort! puff! scream!—here he comes straight-bent through these vernal woods, like the Asiatic cholera cantering on a camel. Stand aside! Here he comes, the chartered murderer! the death monopolizer! judge, jury, and hangman all together, whose victims die always without benefit of clergy. For two hundred and fifty miles that iron fiend goes yelling through the land, crying “More! more! more!”

Through the success of these stories he evidently earned back the trust of publishers enough to submit something longer, first with the serialized novella Israel Potter and finally, The Confidence-Man. When he completed the manuscript in the autumn of 1856, Herman handed it off to his brother Allan to see it through to publishing and boarded a steamship for Europe. He’d spend the next six months or so traveling through Scotland, England, Greece, Turkey, Egypt, Jerusalem, and Rome. It was a grand tour of Europe and the Holy Land he’d been dreaming about for years.

On his way back home Herman stopped in London where, to his surprise, he found copies of The Confidence-Man already for sale on bookshelves. One can only imagine his state of mind — inspired, exhausted, and hopeful for the revival of his career upon his return to Pittsfield — as he sat down to take in the early reviews.

“He has ruined this book, as he did with Pierre, by a strained effort after excessive originality,” wrote the London Literary Gazette. The reviewer for the Illustrated Times was baffled by its meandering, non-linear structure. “After reading the work forwards for twelve chapters and backwards for five, we attacked it in the middle, gnawing at it like Rabelais’s dog at the bone, in the hope of extracting something from it at last. But the book is without form and void.” Even the favorable reviews seemed to be looking ahead to his next novel which they hoped wasn’t quite so… eccentric.

When Melville reached New York at the end of May, he found that reviews stateside were even more vicious. “Mr. Melville seems to be bent upon obliterating his early successes,” suggested one review with exasperation. Another, echoing the London critics, threw its hands up in confusion: “In fact we close this book — finding nothing concluded, and wondering what on earth the author has been driving at.” And twisting the knife of paranoia, the Worcester Palladium insinuated that the low opinion of his new novel was shared even by his inner circle. “Even the most partial of Mr. Melville's friends must allow that the book is not wholly worthy of him.”

The door on his career as a novelist was being slammed shut. After reading the London reviews, Melville had briefly stopped in Liverpool to see Nathaniel Hawthorne where he was serving as the U.S. Consul. Hawthorne recorded his thoughts on their meeting in his journal, writing that Melville had “pretty much made up his mind to be annihilated.” He apparently said much the same thing to his family back home, indicating he was “not going to write any more at present & wishes to get a place in the N.Y. Custom House."

The Ship

While Herman’s fortunes were looking increasingly grim as the 1850s rolled on, his brother Thomas was enjoying a wave of success. Tom was Herman’s youngest sibling by about 10 years, born in 1830 and just two years old when their father died. Herman was out the door and manning the mastheads before Tom turned 10, but always maintained a fondness for his younger brother in the short spans they occupied the same place.

When Herman returned from his years at sea in late 1844, Tom was about to turn 15 and no doubt riveted by the wild Pacific adventures that would become his early novels. After his 16th birthday, he could wait no longer. Tom joined the crew of a whaler, the Theophilus Chase, and would hardly be on dry land for the next several decades. So touched was Herman to have Tom follow in his footsteps that he dedicated Redburn, about his own first sea voyage, “To my younger brother, Thomas Melville, now a sailor on a voyage to China.”

But rather than finding excitement in jumping ship on a remote island or participating in a mutiny like his brother, Tom flourished within the hierarchy or whaling and merchant ships and rapidly ascended through the ranks. His adventures may have been less dramatic, but by the mid-1850s he had achieved something which Herman still had not: a sustained career.

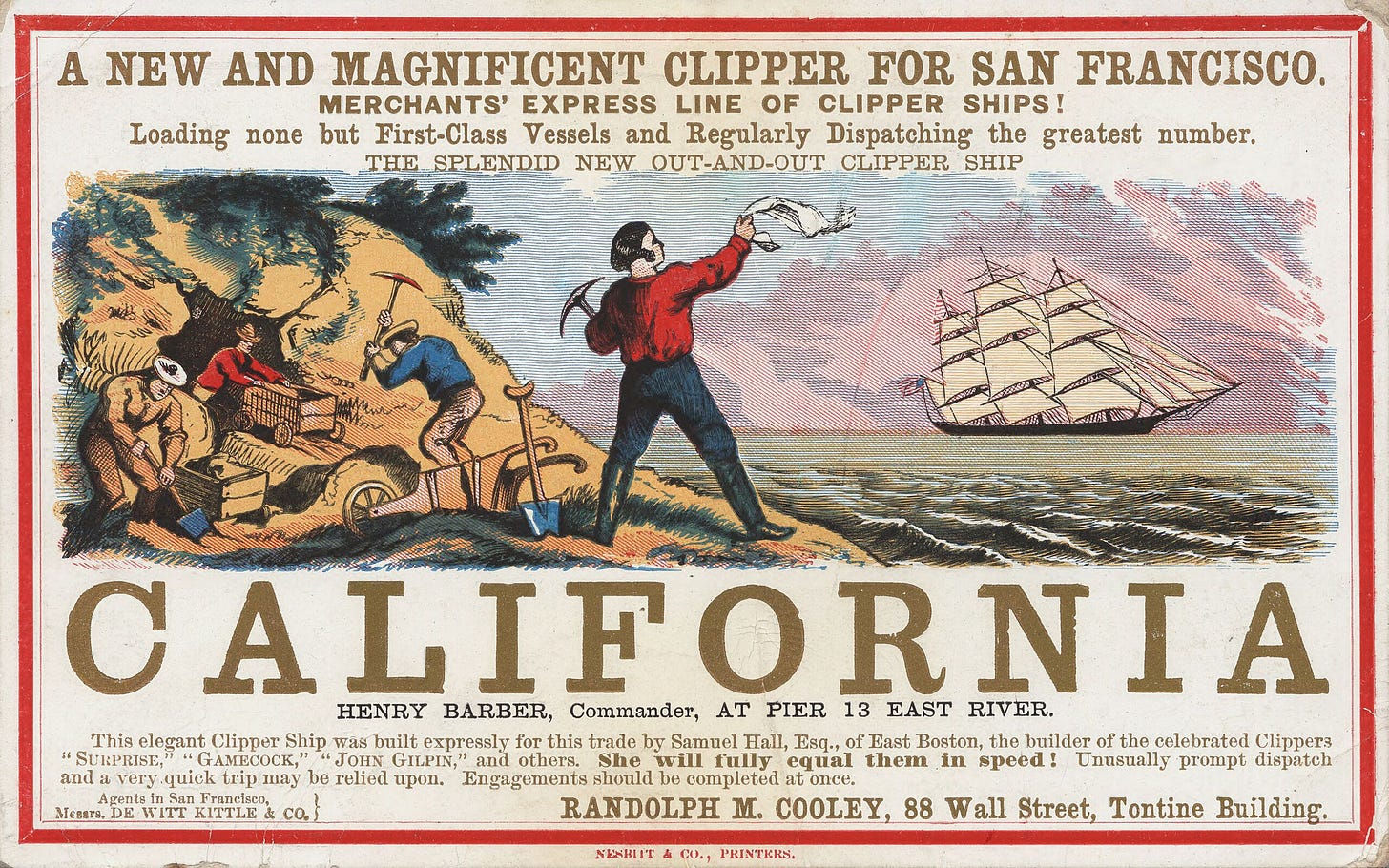

By 1855, Thomas was serving as first mate of the Meteor clipper ship alongside Captain Samuel W. Pike. The Meteor, built in 1852, was designed not only for breakneck speed but for breaking records. It was just a few years earlier that prospectors had discovered gold in California, and there was desperate need to shorten the time it took to deliver fresh labor and supplies. In the early days of the gold rush, it could take ships up to six months to sail around South America; clipper ships cut that in half.

This painting by an unidentified Chinese artist “shows the fully rigged ship METEOR sailing in calm waters and flying an American flag from its mizen mast.”

Weighing 1,068 tons and measuring 195 feet long, the Meteor was an early participant in the race to cut that time down even further. In October 1852, Captain Pike took part in a race known as The Deep Sea Derby in which 15 ships left in staggered waves from Boston and New York and raced to San Francisco. The winner, The Flying Fish, arrived just 92 days and 4 hours later. (The Meteor had hit some bad weather around the Cape and came in closer to about 113 days.)

Carl C. Cutler, in his 1930 book Greyhounds of the Sea, describes the non-stop, hectic scenes aboard the ships and in the rigging during the derby:

Words poorly describe the grim determination with which the ships were driven; the constant sleepless vigilance with which their sails were trimmed and sweated up to make the most of every vagrant puff of air; the untiring work of wetting down canvas to hold the wind. Catlike veterans of twenty handed their sails in whistling squalls that put polished teak rails three feet under swirling green water or took another "small pull on lee fore braces" as they smashed to windward under steel bellied topgallants past stout craft hove to under a goose winged top-sail.

In January 1857, Tom wrote home from Hong Kong with some exciting news: the voyage was to be prolonged by some considerable amount of time to make additional stops in Manila and Calcutta, and Captain Pike decided to return home on another ship. Tom was to be given full command of the Meteor.

When he arrived in Boston Harbor two years later in January 1859 for an all-too-short visit home, present to welcome him home was Herman, who was in town to give a lecture on the South Seas the following week. Delivering this and other lectures around the country had been keeping Herman afloat for the last few years, to mixed receptions. Despite having just returned from spending four years in that part of the world — albeit on a very different sort of journey — Tom stuck around to attend the lecture on the 31st, surely whooping it up for his brother amid the half-empty hall. A few weeks later Tom was on another sprint to San Francisco, this time with a complete set of his brother’s novels on board.

When he returned in early 1860, Tom found that his brother was not doing well. He was suffering from rheumatism in his back, sciatica, and possibly depression. The country was on the brink of civil war and relatives of his were recalled to active duty. He’d been forced to sign over ownership of Arrowhead to his father-in-law to settle his financial obligations, then given in turn to his wife Lizzie. Friends worried about his mental state. “Herman Melville is not well,” wrote his neighbor Sarah Morewood, clarifying: “do not call him moody, he is ill.”

To Tom, his older brother was still the thrill-seeking, almost mythological seafarer who had slain leviathans, befriended cannibals, and hitchhiked a million miles back home solely on his wits. All he needed was another spell out on the open ocean — not as a paying passenger but once more “as a simple sailor, right before the mast.” Herman could hardly have put up much of an argument; the pleasures (and pains) of travel were the subject of his most recent lecture circuit, telling audiences that travel “is as a new birth” and “essential to healthy life,” no matter how near or far you’re able to go. “A trip to Florida will open a large field of pleasant and instructive enjoyment. Go even to Nahant, if you can go no farther —that is travel.”

His family encouraged the voyage, hopeful that it might have a restorative effect on his health. His father-in-law, ever eager to get his good-for-nothing son-in-law out of town, offered to "do anything in my power to aid your preparation." At the last minute, Herman agreed. They would set sail in just a few weeks.

The voyage was expected to last about a year, first stopping in San Francisco, then to Manila, and finally returning Herman to the South Pacific. He was not only optimistic about what lay ahead, but looking forward to spending so much unimpeded time with his brother, who he probably hadn’t seen for more than fits and starts since Tom was just a boy.

I anticipate as much pleasure as at, at the age of forty, one temperately can, in the voyage I am going. I go under very happy auspices so far as ship & Captain is concerned. A noble ship and a nobler captain - & he my brother. We have the breadth of tropics before us, to sail over twice; & shall round the world. Our first port is San Francisco, which we shall probably make in 110 days from Boston. Thence we go to Manilla - & thence, I hardly know where… The prime requisite for enjoyment in sea voyages, for passengers, is 1st health — 2d good-nature. Both first-rate things, but not universally to be found. At sea a fellow comes out. Salt water is like wine, in that respect.

The brothers headed to Boston Harbor where the Meteor was docked and, perhaps at the request of their family, had one quick pit stop to make before setting off.

The Daguerrean establishment on Winter street

Once in Boston, Herman and Tom stowed their gear on the Meteor and walked about 15 minutes into the city toward an ambrotype shop owned by “Davis & Co.” at 2 Winter Street, on the corner of Washington.

By the late 1850s, ambrotypes — from the Greek ambrotos ("immortal") and typos ("impression") — had replaced daguerreotypes as a cheaper alternative based on the wet collodion process. In short, this process allowed for the creation of positives or negatives which could then be used to create an unlimited number of reproductions. The ambrotype used the same chemical process but was a photo positive printed directly on a small sheet of glass. (For a more technical explanation, check out one of these videos). Photographers could potentially churn out hundreds a day, becoming so abundant (and long-lasting) that there are thousands listed on eBay at any time.

Davis & Co. was the studio of Philemon Davis and his assistant John D. Andrews. How Herman and Tom ended up at Davis & Co. is unclear, though the firm had a rather unique and boastful advertising strategy in local newspaper, offering daguerreotypes and ambrotypes for 10 (and later 25) cents “equal, if not superior to those made at any other establishment in the world.” On occasion, Davis & Co. even ran advertisements in the form of a cheap Shakespearean sonnet:

Citizens and strangers, we call your attention

To the Daguerrean establishment on Winter street,

As it is the only place worthy of mention,

Where pictures are executed correct, life-like, and cheap.

The present proprietors of this popular place

Are determined to please and give satisfaction,

Then he not deceive by those who themselves disgrace,

By making pictures that are a mere imitation.

Good Daguerreotypes make beautiful presents,

And are very appropriate at any time;

You can procure them for twenty-five cents.

And they will both correctness and beauty combine.

The Daguerreotype house of Davis & Co.

Is on Washington, corner of Winter street,

Where hundreds of our citizens daily go,

And have their pictures taken fine and neat.

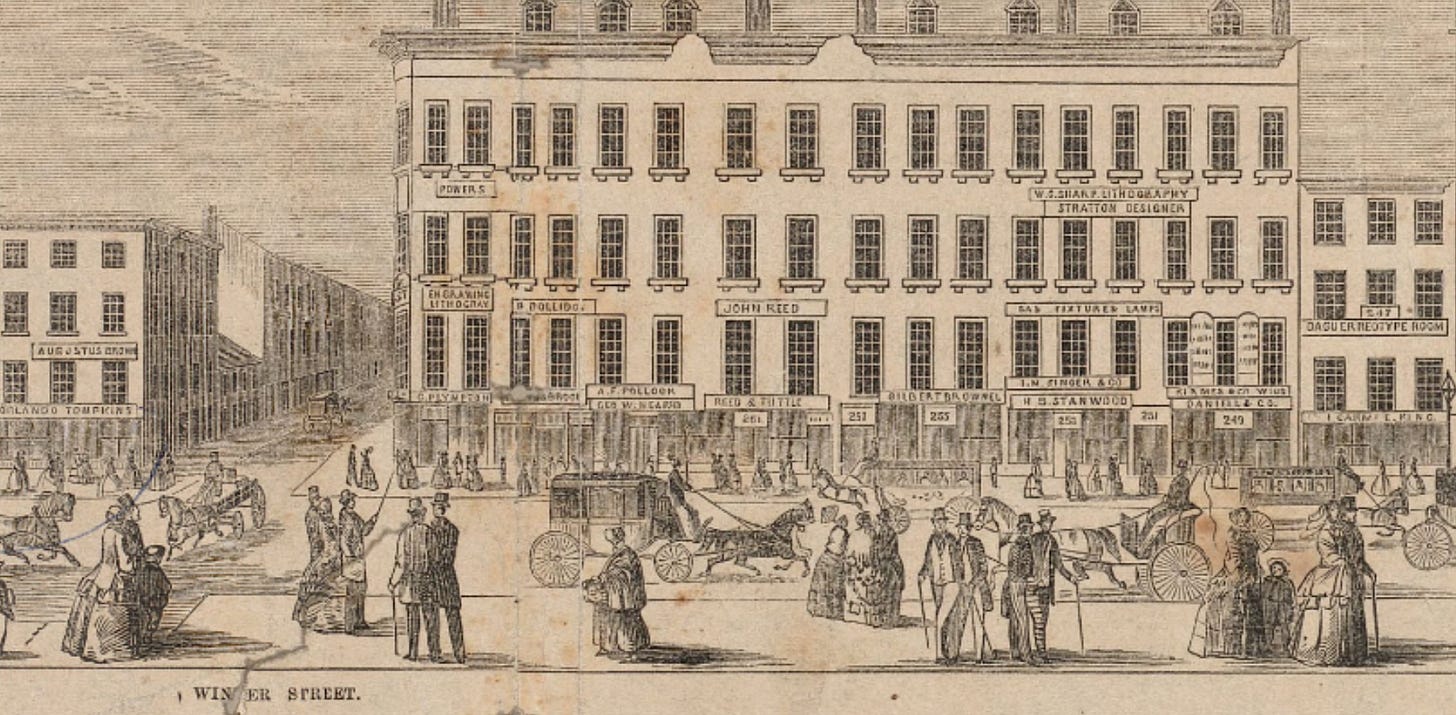

For anyone familiar with Boston, the intersection of Winter and Washington is now the heart of the Downtown Crossing district. It was just as busy at the time, possibly moreso. This image shows the exact corner from Washington St. in 1853. (If you look closely toward the right, you’ll see represented a “Daguerreotype Room” at number 247, though in 1860 this one was owned by a different photographer, Charles Swift.)

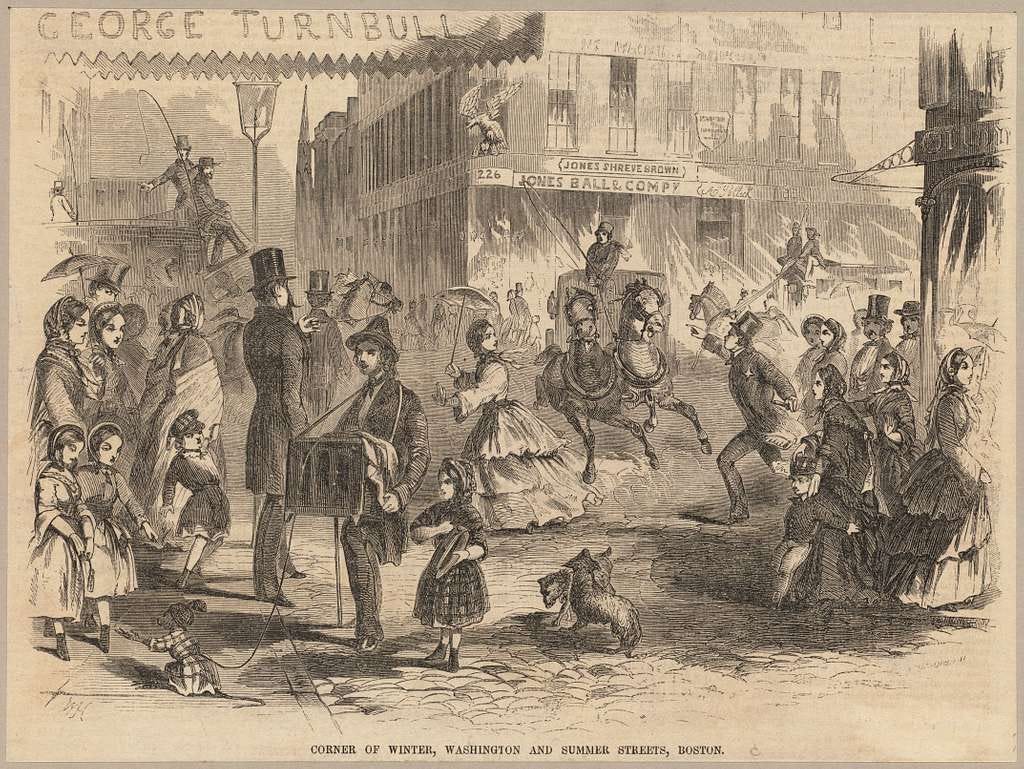

Ballou’s Pictorial Magazine presented a much more chaotic scene at that corner in its June 1857 issue, drawn by none other than Winslow Homer, at the time working as a commercial illustrator. According to the accompanying article, the intersection was “one of the busiest and most brilliant spots in all Boston.”

Based on the accompanying article, the scene was drawn from almost directly in front of Davis & Co., ensconced between jewelers, an apothecary, a dry goods store, and an Italian organist with a monkey begging for change.

The local view upon this page, drawn expressly for us by Mr. Winslow Homer, a promising young artist of this city, is exceedingly faithful in architectural detail and spirited in character, and represents one of the busiest and most brilliant spots in all Boston.

The sketch is made from the north sidewalk of Winter Street. The most prominent building in the view is the large stone structure at the corner of Washington and Summer Streets, the lower story of which is occupied by the magnificent jewelry establishment of Messrs. Jones, Shreve, Brown & Co., and which vies in splendor and attraction with similar magazines in New York, London or Paris. This is always an attractive spot, and you can scarcely pass it any hour of the day without finding loiterers at the windows, with bright eyes gazing on the kindred diamonds, or scanning the superb plate, watches and rings there displayed in dazzling profusion… Opposite this establishment is that of Orlando Tompkins, apothecary, which has recently been refitted and renovated in the style of the Renaissance, with carving, gilding, fresco-painting, mirrors, marble, etc., in the most approved style of luxury. We merely show the corner of this store. The name of George Turnbull appears upon the awning in front of his store, No. 5 and 7 Winter Street, which projected within our artist's field of vision. Turnbull’s is another noted Boston establishment, and a fine specimen of the retail dry goods store…

Here we have a carriage dashing up at rather an illegal rate of speed which might endanger the lady at the crossing, but for the gentlemanly policeman who is stationed here to ensure the safety of pedestrians and moderate the ardor of charioteers, and who steps forward to lend his assistance and interpose his potential authority. In another place we have an itinerant Italian with his organ, on the summit of which resides habitually a painful caricature of humanity in the guise of a monkey, attired in shabby habiliments, whose chief offices are to hold his hat for money and amuse the juveniles with his antic capers. Promenaders of both sexes, and pedestrians of all ages, complete the lively picture.

After weaving through the crowds and dancing monkeys, the brothers posed side-by-side, their heads likely held in place by clamps to keep still for the 5-10 second exposure. Twenty minutes or so later, they would have walked out of the shop with their photo in hand, looking like “twin grizzly bears.”

The original ambrotype you see here, like virtually all the known photos of Melville, is at the Berkshire Athenaeum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Davis & Co., however, was known for their “double camera” which produced a second ambrotype simultaneously. More on that photo, which has been missing for something like 60 years, in next week’s follow-up post.

The Voyage

So how did the supposedly-restorative voyage for the old salt go? Well, as they say, you can’t cross the same river — or ocean — twice. Fifteen years had passed since he returned from the Pacific, and Tierra Del Fuego was no Tahiti.

Herman felt sea sick from the get-go, too ill to read the books he brought. Then, after ten days at sea the Meteor collided with another ship, a poor omen though the ship thankfully avoided major damage. Even as the weather grew warmer by the day, Melville reported in his journal being in “Doleful Doldrums,” with the whole ship’s crew "given up to melancholy." All they had was a chess set whipped up by the ship’s carpenter, ever the wizard.

As the Meteor approached the Cape the weather turned violent; Melville recorded in his journal that they faced “several gales, with snow, rain, hail, sleet, mist, fog, squalls, head-winds.” The ship’s boy, Charlie, crashed into the pig-pen, destroying the enclosure and letting the animals out, one of whom drowned. The mainsail, mizzen topsail, and staysail were all split to pieces. “Days short,” he wrote, “but not sweet.”

There may be no better insight into Herman’s state of mind than his miserable report about his experience of traversing Tierra Del Fuego, the gamesome spirit of adventure and curiosity present in his books now virtually extinguished.

Horrible snowy mountains - black, thunder-cloud woods - gorges - hell-landscape… At last we came in sight of land all covered with snow — uninhabited land, where no one ever lived, and no one ever will live — it is so barren, cold and desolate…. There are some "wild people" living on Terra del Fuego; but it being the depth of winter there, I suppose they kept in their caves. At any rate we saw none of them.

Incessant winds repeatedly swept the sailors off their footing, nearly throwing them overboard. Then, on August 9, while at the very tip of the continent, a young man from Nantucket fell from the main topsail yard, splitting his head open and instantly killed. The sight of it seemingly traumatized Herman:

Calm lasting all day - almost pleasant enough to atone for the gales, but not for Ray's fate, which belongs to that order of human events, which staggers those whom the Primal Philosophy hath not confirmed. — But little sorrow to the crew - all goes on as usual - I, too, read & think, & walk & eat & talk, as if nothing had happened — as if I did not know that death is indeed the King of Terrors - when thus happening; when thus heart-breaking to a fond mother - The King of Terrors, not to the dying or the dead, but to the mourner - the mother. — Not so easily will his fate be washed out of her heart, as his blood from the deck.

When the ship mercifully docked at San Francisco’s Vallejo Street wharf in mid-October, Herman had had enough. Rather than continuing on to Manila and beyond, he spent a week in the city and went home to Pittsfield via a steamship. This time, though, he opted out for a passage that delivered passengers to Panama, crossing the isthmus by train. To the surprise of all in Pittsfield, he was home by November.

It’s no wonder that Melville had finally relented in his opposition to having his photo taken in May 1860. He had been “annihilated” by critics and readers alike, emasculated by ceding Arrowhead to his father-in-law and wife to pay off innumberable debts, and, as he learned, wasn’t even the most notable globe-traveling sailor among his own siblings.

The time had come to be oblivionated by a photograph.

References

Stanton Garner, The Civil War World of Herman Melville (1993)

Jay Leyda, The Melville Log (1951)

Hershel Parker, Herman Melville: A Biography, Vol. 2, (2005)

Laurie Robertson-Lorant, Melville: A Biography (1996)

Eleanor Melville Metcalf, Herman Melville: Cycle and Epicycle (1953)

Merton Sealts, Melville as Lecturer (1957)

Incredible post. I am currently reading Typee for the first time and paused it to read this when I got the notification!

Typee is super good, btw for anyone curious.

For the picture, which one is Herman, sitting or standing? Thanks for this great work!

Typo: "The voyage was expect to last about a year"