EXTRACTS: Le Cachalot Blanc

; or, when did Albert Camus first read Moby-Dick?

As I wrote about in last week’s post, if you’ve ever detected a distinct Melvillian tinge in the writing of Albert Camus, it’s not just your imagination. Camus was unequivocally an admirer and devotee of Melville, returning again and again to his novels, stories, and biographies throughout his life and putting him shoulder to shoulder with the likes of Shakespeare, Tolstoy, Hugo, and Nietzsche.

But after detailing Melville’s influence on Camus through decades of his writing and thinking, there was one thing I couldn’t let go: according to the experts, he didn’t read Moby-Dick until after he had finished writing The Myth Sisyphus, which seemed to me to be the work most indebted to the white whale. The question of how we’re to respond to the "unreasonable silence" of the universe unmistakably mirrors one of the core ideas presented in Melville’s “wicked” book. What are Ahab and Ishmael if not two distinct pathways taken in the face of this question?

Admittedly, the topic of ‘when did Albert Camus first read Moby-Dick’ is among the more niche that I’ve addressed here, but I thought it might still be worth seeing if this claim holds water, and learn a bit about the Melville renaissance happening across the ocean.

An Unreasonable Silence

For all the explicit influence it had on his novel The Plague, Camus biographers and scholars seem to agree that he came to Moby-Dick somewhat late in his life. In fact, it’s supposed to be the spring or summer after finishing Sisyphus, which he finished in December 1940 and finalized with his publisher in February 1941.

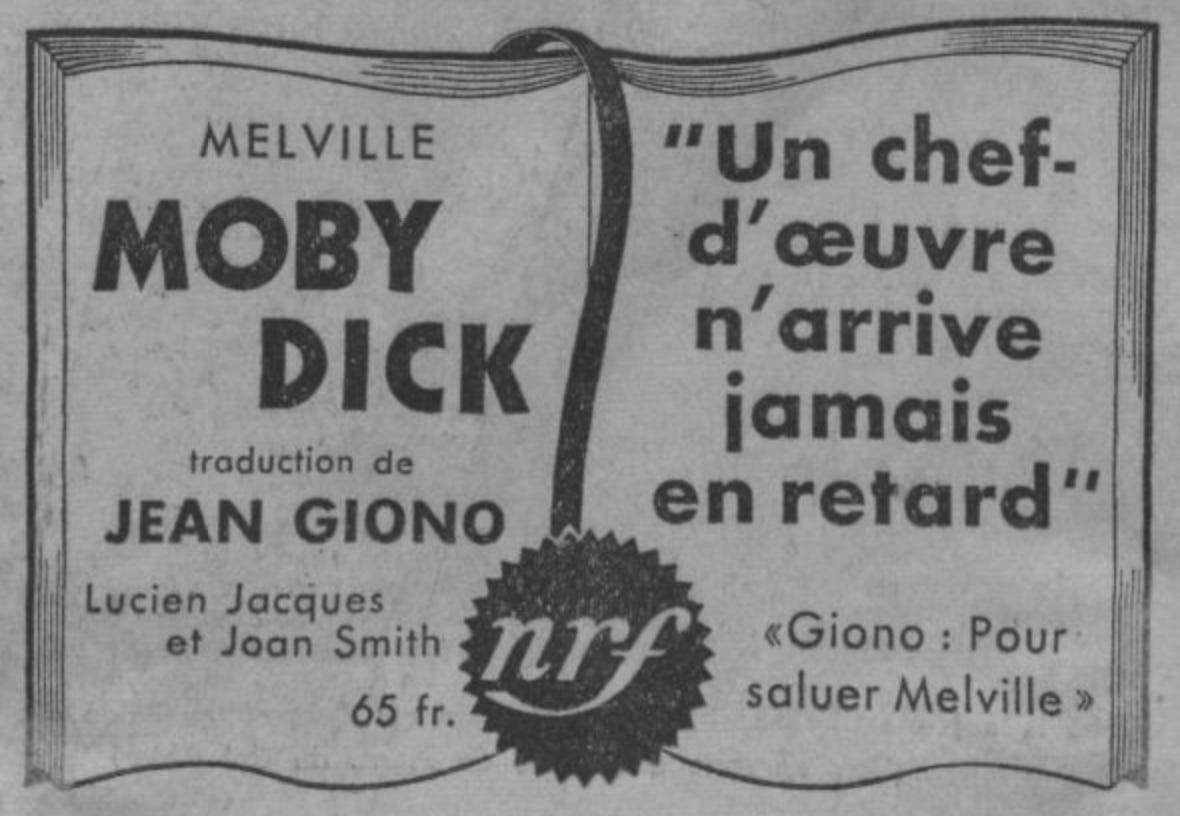

Perhaps with some free time on his hands, Camus picked up and read a brand new translation of Moby-Dick by Lucien Jacques, Joan Smith, and Jean Giono, published by Éditions Gallimard in May. The book, ironically, was announced in newspapers with the tagline: “A masterpiece never arrives late.”

Camus scholar Leon S. Roudiez, who wrote extensively about the links between Melville and Camus, stated in a 1961 article that it was “quite unlikely that he became acquainted with a French version” prior to this translation and was “thus reasonable to suppose, until evidence to the contrary is found in his private notebooks and diaries, that Camus read Moby-Dick in the Gallimard edition of 1941.” (Roudiez allowed that it was possible — if “improbable” — that he read it earlier in the original English.) The same timeline was given by Philip Thody, editor of a collection of Camus’ notebooks, again writing that he “probably” first read the 1941 translation.

Ignoring for now Roudiez’ dismissal of the idea that Camus might have read the original English text, the main reason everyone seems to agree on this point is that the 1941 Gallimard edition is actually considered to be the first true French translation of the book, arriving a leisurely two decades after the start of the Melville Revival.

But then, what are we to make of this note in Camus’ journal from three years earlier?

There’s no other context in the journal for what prompted this entry about Melville, but Camus appears to have understood the basic outline of his life as early as April 1938, while still living in Algeria. Roudiez acknowledged the journal entry in a footnote, but thought it merely suggested that Camus had read other Melville works which had been translated first.

Germaine Brée informs me that the first reference to Melville she has seen in Camus’ notebooks goes back to April, 1938. The reference is to Melville himself rather than to any of his works, but this would seem to transform the likelihood [that Camus had read Billy Budd etc.] into a near-reality.

Who or what prompted Camus to read Melville is still not known. If he indeed made his initial discovery of Moby-Dick through the Gallimard edition… he must have read it as soon as it appeared, during the summer of 1941. … This suggests the likelihood that he was already acquainted with one or more of Melville’s works, perhaps with Billy Budd which had been translated in 1935 by Pierre Leyris. … Reading Billy Budd might also have led him to Benito Cereno and Pierre, both translated by Leyris and published in 1937 and 1939 respectively.

Even more puzzling was something so obvious that I couldn’t (and still mostly can’t) believe that I’m not completely misunderstanding. The issue is that Camus specifically mentions Moby-Dick in the Myth of Sisyphus, and praises it as one of the very few novels to illustrate his concept of the Absurd. Unlike Dostoevsky, he writes, a “truly absurd” book like Moby-Dick fully commits to the premise that there are no easy, philosophical answers to alleviate our anxiety; no hope that there’s more to life than what we perceive.

In fact, amid this discussion Camus writes that he “could… list some truly absurd works” but chooses only to name one, in a footnote:

Slightly earlier in the essay, Camus puts Melville in line among the “great novelists” like Balzac, Stendhal, Proust. The operative word here is “novelist.” While it’s true that Typee and Pierre had been translated into French in the 1930s, his more accomplished works which had been brought to France by that point were Billy Budd and Benito Cereno which, of course, are short stories.

Neither Roudiez or Thody make anything of these two Melville mentions, which should give an armchair “scholar” like myself some pause. Without any other way to explain this, I dove into the history of French translations of Moby-Dick to try to figure out what other opportunities Camus would have had prior to 1941 — and prior to writing Sisyphus — to encounter this “truly absurd” novel.

Les Cachalots Blancs

Though it likely has no bearing on when Camus first read it, the first opportunity the Francophone public would have had to encounter Moby-Dick came just a few years after it was published. In February 1853, the Revue des Deux Mondes published a 25-page summary by Paul-Émile Daurand Forgues. The summary, which I’ve attempted to translate here, begins:

This is a campaign aboard the Pequod that we are going make today, aboard the Pequod, one of the oldest whalers on Nantucket Island. The Pequod, so named in memory of one of the redskin tribes that civilization destroyed by establishing itself on the North American coasts.

See it in the port, this venerable ship, this patriarch of the seas, browned under the suns and storms of the four oceans, like a grenadier of the great army under the skies of Rome, Thebes, Santo Domingo and Moscow! For more than fifty years that she has been crossing the seas, mutilated, refitted in twenty places, she has Japanese masts, spars from Chile, Polynesian shrouds, moss, vegetation from almost all points of the globe, which make her a sort of silty and greenish beard like that of a mythological river.

The extended summary goes into considerable depth about the plot, major and even minor characters, and encounters with other ships. Amazingly, though, he writes Ishmael completely out of the story. Neither he, his melancholy, nor his role as the narrator are mentioned even once. (Point: Ahab)

Le Cachalot Blanc

The next white whale spotted in France was a 1928 translation by Marguerite Gay. Le Cachalot Blanc was published by Gedalge as part of a series of classics adapted for young audiences, abridging the text to a still-respectable 256 pages.

Although the translation boiled down some of the blubber, that doesn’t necessarily mean that Gay strayed too far from the remaining original text — even in sections that do little to move the plot forward. For example, take this section from Chapter 20: All Astir in the original:

And though this also holds true of merchant vessels, yet not by any means to the same extent as with whalemen. For besides the great length of the whaling voyage, the numerous articles peculiar to the prosecution of the fishery, and the impossibility of replacing them at the remote harbors usually frequented, it must be remembered, that of all ships, whaling vessels are the most exposed to accidents of all kinds, and especially to the destruction and loss of the very things upon which the success of the voyage most depends. Hence, the spare boats, spare spars, and spare lines and harpoons, and spare everythings, almost, but a spare Captain and duplicate ship.

Compare that to Marguerite Gay’s translation in Le Cachalot Blanc (followed by a rough translation back to English).

Although this remark also applies to other ships of the merchant navy, it is even more accurate with regard to whalers. Besides the great duration of the whaling expedition, the numerous articles used for fishing and the impossibility of replacing them in the distant ports usually frequented, it must be remembered that, of all ships, whalers are the more exposed to a thousand kinds of accidents, in particular to the destruction and loss of the very objects on which the success of the journey depends. Hence, spare whaleboats, spare spars, spare lines and harpoons and all spare things except a spare captain and the duplicate ship.

Roudiez writes, however, that Gay’s translation “does not seem to have made much of an impression upon the public,” a claim he supports with the fact that Giono, Jacques, and Smith (translators of the 1941 Gallimard edition) weren’t even aware it existed when they started their own version about a decade later.

Nor, he says, is it likely that Gay’s translation would have landed with the then 15-year-old Camus. “At that time Camus was a scholarship student at the Lycée d’Alger and an enthusiastic member of the Racing-Universitaire soccer team: he could not have had much spare time for individual exploration in American literature.” Never mind that two years later the precocious student was struck with tuberculosis and began casually studying Ancient Greek and German philosophy while he recovered.

“Une Nuit a l'Hotel de la Baleine”

Even if we believe Roudiez that Camus was too busy convalescing and/or playing soccer, we still need to account for another French translation — or a partial one, anyway. Five chapters of Moby-Dick were translated in full by Théo Varlet in the September 1931 issue of a magazine titled Le Crapouillot (“the little toad”).

Varlet was a prolific translator and appears to have had a taste for sea stories and adventure novels. His body of work includes dozens of translations of Robert Louis Stevenson, Rudyard Kipling, and even a translation of Typee in 1926 retitled “Un Eden cannibale.” This short excerpt of Moby-Dick, given the title “A Night at the Whale’s Hotel” (???) presented chapters 2 through 6 of the original text, opening with a preface explaining the context of the book. Varlet also touches on the reluctance of French publishers to provide a complete translation due to its length and unusual composition.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Americans had become the masters of whale fishing and especially sperm whale fishing. Two small ports, Nantucket and New Bedford, had grown tremendously thanks to this dangerous industry. Herman Melville, who served for several years on a whaling ship, published a novel about 1850 called Moby Dick which may be considered the pinnacle of maritime literature of any country. Until now, French publishers had hesitated to provide a complete translation of Moby Dick because of its length and also its composition, which is a mixture of romance, technical details and philosophical ramblings, of a rare quality in fact.

Curiously, Varlet added that his own complete translation of this “astonishing work” would appear soon “in a deluxe edition by Éditions du Bélier.” According to a biography, Varlet did finish the translation but even the highly-regarded and experienced translator couldn’t overcome the reluctance of French publishers to this bizarre novel. It never saw the light of day and may have been lost after Varlet’s death in 1938.

A “Most Astonishing Book”

Finally, we come to the translation for Éditions Gallimard by Jean Giono, Lucien Jacques, and Joan Smith. Published in 1941, it was, as we know, too late to have an influence on Sisyphus, right? Well, that’s actually still not quite right.

The idea for the translation began with novelist Jean Giono, who came across an English version of the book in 1935 and, like the rest of us, became consumed by it.

Melville’s book was my foreign companion. I took it with me regularly on my hikes across the hills. As soon as I entered those vast, wavelike but motionless solitudes, I’d sit down under a pine and lean against its trunk. All I needed was to pull out this book, which was already flapping in the wind, to sense the manifold life of the seas swell up below and all around me. Countless times I’ve felt the rigging hiss over my head, the earth heave under my feet like the deck of a whaler, and the trunk of the pine groan and sway against my back like a mast heavy with wind-filled sails.

Despite the difficulty he had reading the book in English, particularly the archaic naval terms, Giono called Moby-Dick “the most astonishing book” he’d ever read. And like many readers today, he too felt an instinctual need to pass on the transformative experience. Giono immediately shared the book with his friend, artist Lucien Jacques, with whom he ran the literary journal Les Cahiers du Contadour.

But sharing it with a single friend wasn’t enough. Giono felt a responsibility to translate the entire book so that it could be read by the entire Francophone world. It didn’t take much to convince Jacques to come along for the voyage.

It was quite easy for me to share my passion for Moby-Dick with Lucien Jacques. A few evenings spent pulling away on our pipes by the fire while I translated certain passages, clumsily but with enthusiasm, were enough to convince him. From this point onward, the book became our mutual dream, one we soon wanted to share with others. The matter was settled when we realized that Melville himself was handing us the principles that would guide our work. “There are some enterprises,” he says, “in which a careful disorderliness is the true method.” This statement corresponded so exactly with our own natures and with the substance of his book, that everything seemed to be settled in advance, and there was nothing left to do but let things take their course. As is said many times in Moby-Dick, and far more eloquently than you could ever say it yourself: When the whale has been harpooned, you have no choice but to go after it; when it sounds, you have to wait for it; and when it breaches, you have to go after it again. And so it was accomplished.

The “disorderliness” in this case referred to a not-so-small problem before them: Giono wasn’t really a translator, nor did he have the attention span to tackle such a long and difficult book. Jacques, meanwhile, couldn’t speak or even read English.

Enter another of Giono’s friends, Joan Smith, an English antique dealer living in Provence who they convinced to join the motley team. The order of operations was that first Joan Smith would translate the book word-for-word into French, without embellishment or accounting much for differences between the languages. Lucien Jacques would then clean up the stilted sentences and turn it into passable French. Finally, Giono would take Jacques’ version and try to infuse the words with the spirit of the Melville’s original English. His description of the process will be recognizable to anyone who has been similarly overcome by the language of Moby-Dick:

Like the mountain, the torrent, or the sea, one of his sentences rolls, lifts, and falls in complete mystery. It transports you; it drowns you. It reveals the realm of images in the blue-green depths, where the reader moves like a slimy piece of seaweed; or else it encircles you with mirages and echoes off deserted, airless peaks. It presents you with a beauty that resists analysis but strikes with violence.

We persisted in trying to reproduce its depths, its chasms, its abysses and its summits, its rockslides, its forests, its darkened valleys, its precipices, and the heavy mortar compounded from it all.

The translation-in-triplicate took several years to complete, most often delayed by Giono’s fleeting attention span. When they finished, Giono and Jacques decided to serialize the entire book in their literary journal over the course of 10 months from May 1938 to March 1939, the last issue the journal sent to press before it shuttered in anticipation of the war.

Now, recall Camus’ journal entry where he laments the tragic arc of Melville’s life, recorded in April 1938 just before the first part of the serialization. In other words, we know that at that very moment Camus was interested in Melville. Is it difficult to believe that he would seek out Melville’s best known novel, finally available in French?

It’s impossible to say, of course. But even if Camus passed even on that opportunity to read it, finally we come to the one we know he did read. Two years after the final serialization in Cahiers, in the middle of the German occupation of France, the Giono translation was collected and reprinted by Éditions Gallimard in May 1941. Camus, we know for sure, picked up one of these copies and made his copious notes in the margins.

“Are there any of you Bouton-de-Roses that speak English?”

Wherever you fall on the issue of which of the above translations Camus read first, there’s one last caveat: although Camus couldn’t (or wouldn’t) speak much English, he could read it “fairly well” according to biographer Olivier Todd. In fact, he studied English in high school while simultaneously working as a translator for a maritime broker, converting lists of provisions from English to French. In the 1930s, moreover, Camus had a close friend named Yves Bourgeois, a high school English teacher with whom he traveled extensively throughout Europe. Is it really so “improbable” that he, like Jean Giono, got his hands on an English version of the text and slowly worked through the arcane English?

The hardest thing to square with any of this is that Camus, for all he talked about his love for Melville, simply never mentioned reading Moby-Dick earlier than 1941 aside from the hints left in Sisyphus. And while I’ve done what I could without ever leaving home, real Camus scholars have (I presume) pored through archives around the world and I expect would have come across any note that existed.

On the other hand, as I’ve discovered several times in these posts, never assume that the answers have all been found already! The history of Moby-Dick in French is, understandably, a bit outside the purview of a Camus scholar, but it may be worth reconsidering just when he first encountered Melville as well as the influence it had on the development of his thoughts on the Absurd.

References

Albert Camus, Essais (1965)

Albert Camus, Notebooks 1935-1951 (1998)

Albert Camus, Travels in the Americas: Notes and Impressions of a New World (2023, ed. Alice Kaplan)

Olivier Todd, Albert Camus: A Life (1997)

Herbert Lottman, Albert Camus: A Biography (1979)

Robert D. Zaretsky, Albert Camus: Elements of a Life (2011)

James F. Jones, Jr., “Camus on Kafka and Melville: An Unpublished Letter,” The French Review, Vol. 1, No. 4 (March 1998)

Leon S. Roudiez, “Les Étrangers Chez Melville et Camus,” Configuration critique d'Albert Camus; Revue des Lettres Modernes 64-66 (1961)

Jean Giono, Melville: A Novel (trans. Paul Eprile)

Isabelle Génin, “Giono, Translator or Reader of Moby-Dick?", TTR : Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction, Volume 27, Number 1, 1er semestre 2014, p. 17–42

More interesting stuff I didn’t even think about. Translations are interesting. What’s in what’s out . One of my readers speaks Chinese and had a Chinese translation. She said it was hard to read as the sentences were long and it was hard to find the verbs. Pretty much the same in English we thought.