In my post last week, I dug into the first known/surviving image of Herman Melville, a portrait made in his late 20s by artist Asa Twitchell. Here are a few quick odds and ends that I ended up cutting for space/continuity to, uh… complete the picture.

1846? 1847? Pick a Side!

The date of the Twitchell portrait is always given as something like “c. 1846-1847.” This is, of course, because it’s actually unclear exactly when they met, when it was finished, or when it was delivered to Melville in its ornate gold frame. Surprisingly, there’s no mention of the portrait in his or his family’s correspondence, or any other document that might give us a hint, up until that single mention of it in Melville’s 1849 journal where he noted that Twitchell painted his portrait “gratis.”

In the broadest sense, we know it must have been made sometime after Melville returned from his years at sea in late 1844, living with his mother in Lansingburgh. But it’s far more likely to have happened post-Typee, published in March 1846, when he gained a bit of notoriety. On the other end of the range is October 1847, when Melville and his family left the Lansingburgh/Albany area and returned to New York City, on the assumption that it was made when the two men were living just a few miles apart. Still, you can see that these are both just assumptions.

Hershel Parker, in his biography of Melville, says little about the portrait beyond the suggestion that it was done in the spring or summer of 1847 when Melville was “flush with success” after Omoo was published that May. Though he may have earned recognition (and about $400) the previous year from Typee, Omoo was selling better and faster with reviews pouring in from both sides of the Atlantic. Contributing to his feeling of success was his engagement to Elizabeth Shaw in June, or as his sister cheekily put it, having “made arrangements to take upon himself the dignified character of a married man.” With a sisterly knife-twisting she added: “Only think! I can scarcely realize the astounding truth!” They’d be married August 4, a few days after Melville’s 28th birthday.

While I have no more definitive evidence than anyone else, having learned much more about Twitchell’s strategy of climbing family trees and ingratiating himself into Albany’s well-heeled social circles, there may also be another clue narrowing the potential time range even further: the dedication of Omoo to his uncle Herman Gansevoort, eminent Albanian and member of one of the most distinguished families in the area .

My theory, supporting Parker’s idea, is that when Twitchell learned of Melville’s connection to the Gansevoort family in May 1847, he quickly sought him out for a free portrait. As I mentioned last week, even if Twitchell didn’t read the book himself, the dedication and Melville’s connection to the Gansevoorts were both mentioned in the Albany Evening Journal’s review of Omoo from June 25. Could the portrait then be narrowed down to about July 1847, arguably the single most “successful” month of Melville’s entire life? Maybe! The opportunity was exactly the kind of thing Twitchell seems to have sought out early in his career. Melville, for his own part, had possibly never felt so successful in his life, and might never have that feeling again.

There also would have been ample time on Melville’s calendar, for what it’s worth. On July 9th, Melville traveled to Boston to have afternoon tea at a gathering convened on his behalf. (Among those attending was his idol Richard Henry Dana, Jr., to whom he later admitted in a letter that he felt "strange, congenial feelings” when reading Two Years Before the Mast.) He traveled back to New York City the following day to see his friend and mentor Evert Duyckinck. And a few weeks later Melville went up the Hudson to see his uncle/dedicatee Herman Gansevoort in (where else?) Gansevoort, New York, staying for two days. The rest of the month, at least per Jay Leyda’s The Melville Log of his day-to-day activities, was relatively free.

All of this to say that I think it’s safe to remove the “c. 1846-” when dating the portrait, which I’m convinced was made in the summer 1847 when Twitchell saw an opportunity to network a bit with the buzzy literary star in town with a surprising Albany pedigree.

For what it’s worth, it doesn’t seem like the gambit paid off for Twitchell. There’s no catalog of Twitchell’s work, but I did find one reference to a portrait of Leonard Gansevoort which sold at an auction in 1908, four years after Twitchell’s death. But the mere fact that it was sold at an auction among more than a hundred other works indicates that it was just something Twitchell made on his own and for which he never found a home. Leonard — presumably Melville’s notable uncle and not his first cousin by the same name — was a member of the New York State Assembly and Senate, and a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1788, but he also died in 1810. In other words, the portrait was most likely a copy after the one painted by Gilbert Stuart (or possibly Ezra Ames?). This painting, as is the case for much of Twitchell’s work, is unlocated.

Or maybe none of that?

On the other hand, Melvillean Scott Norsworthy hinted at an even more radical idea back in December 2013. What if the portrait sitting never happened at all? In one of his many impressive trawls of the archives, Scott found a notice in the Rondout [N.Y.] Freeman from August 21, 1847 about daguerreotypist Samuel Lyon Walker who was showing off a photo of Melville at Rondout’s Mansion House hotel.

DAGUERREOTYPES WORTH HAVING. Mr. Walker, whose card is in to-days paper is one of the few daguerreotypists who thoroughly understand his beautiful art. That the blessed sun himself can be a very bad painter when maltreated by bunglers is very apparent in the swarms of specters of dismal countenance clad in very blue linen, called by courtesy daguerrean likenesses. Mr. W’s productions are of a very different stamp; remarkable for distinctness, for the absence of the ghastly tints, startling lights and shades, and painful distortions so common; and possessing the transparency, and softness of the best painted portraits. His daguerreotypes of Martin Van Buren, Silas Wright, W. H. Seward, Gov. Bouck and other men of note, have commanded the admiration of the best critics in art. To give the people of Rondout an opportunity of judging of his quality, Mr. W has left some specimens at the Mansion House, embracing Herman Melville, author of “Omoo” &c, Dr. McNaughton of Albany, and other widely known personages.

Rondout was the third largest port on the Hudson (now part of Kingston), and a stopping point for steamboat and stagecoach passengers roughly halfway between Albany and New York. But around 1846, Walker was living in Albany and had a studio just a block or so away from Twitchell’s on State Street.

Scott suggests that Walker, known for his ‘painterly’ photographs, possibly faked the photo using Twitchell’s portrait. Whether this was possible I can’t say (though it’s unclear how he would have had access to the portrait), but it’s also worth considering the reverse. What if Twitchell never met Melville at all, painting a portrait from the daguerreotype and delivering it as a wholly unasked-for gift? Twitchell made many copies from portraits of subjects who died before his time, such as this one of New York Governor De Witt Clinton, who died when Twitchell was eight years old. This could also account for why there’s no mention in any of the family’s correspondence about the portrait, or why Melville had no qualms about hiding it behind a door at Arrowhead and ‘forgetting’ to take it to New York City. Just idle speculation.

It goes without saying that this alleged daguerreotype is now lost, if it existed at all, though it’s not a bad idea to keep an eye on eBay.

A Look at 56 State Street

In the article about Twitchell in the Albany Argus from 1897, in which he described his artistic awakening seeing the three portraits, the writer noted that Twitchell’s first studio in Albany was “in the building on State Street now occupied by Keeler's Sons' restaurant.” State Street, I noted, was also the location given in that February 1846 article in the Lansingburgh Gazette which proclaimed the hometown hero to be a “genius” and a portrait artist of the highest caliber. But it wasn’t until this note about a Keeler’s Restaurant in the late 19th century that I had any leads as to the exact address.

Keeler’s, I learned, was a mainstay of Albany’s fine dining scene for 85 years with several locations around the city. The first, opened in 1884, was located at 56 State Street, at the southwest corner of State and Green Streets. (The ornate Dutch front was added twenty years later.) Here it is in 1902:

As a bit of a visual learner, I often spend time looking for historical photos of sites I’m reading and writing about, just in case by some miracle I find one taken of exactly the storefront or intersection from more or less the same time period.

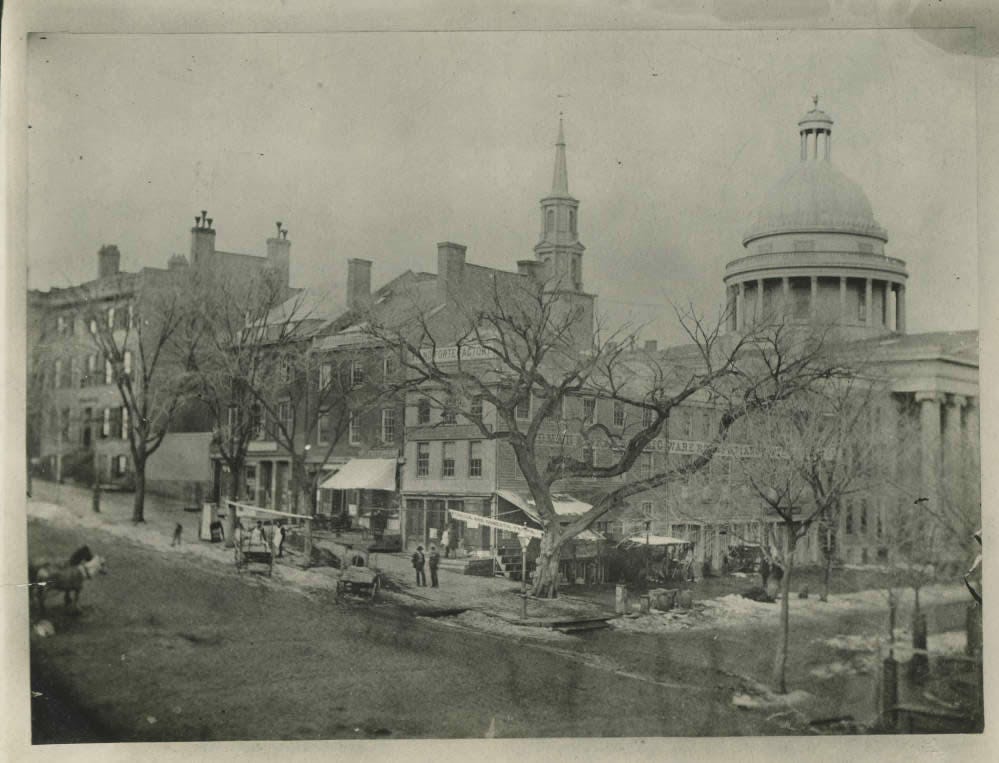

Searching for the southwest corner of State and Green, the first photo I came across was about three blocks away and 18 years too late, showing the corner of State and North Pearl Streets, circa 1865. That’s the old New York State Capitol building in the background, now long gone. Still, it gives a pretty good sense of the Albany that Melville and Twitchell would have known in their mid-40s

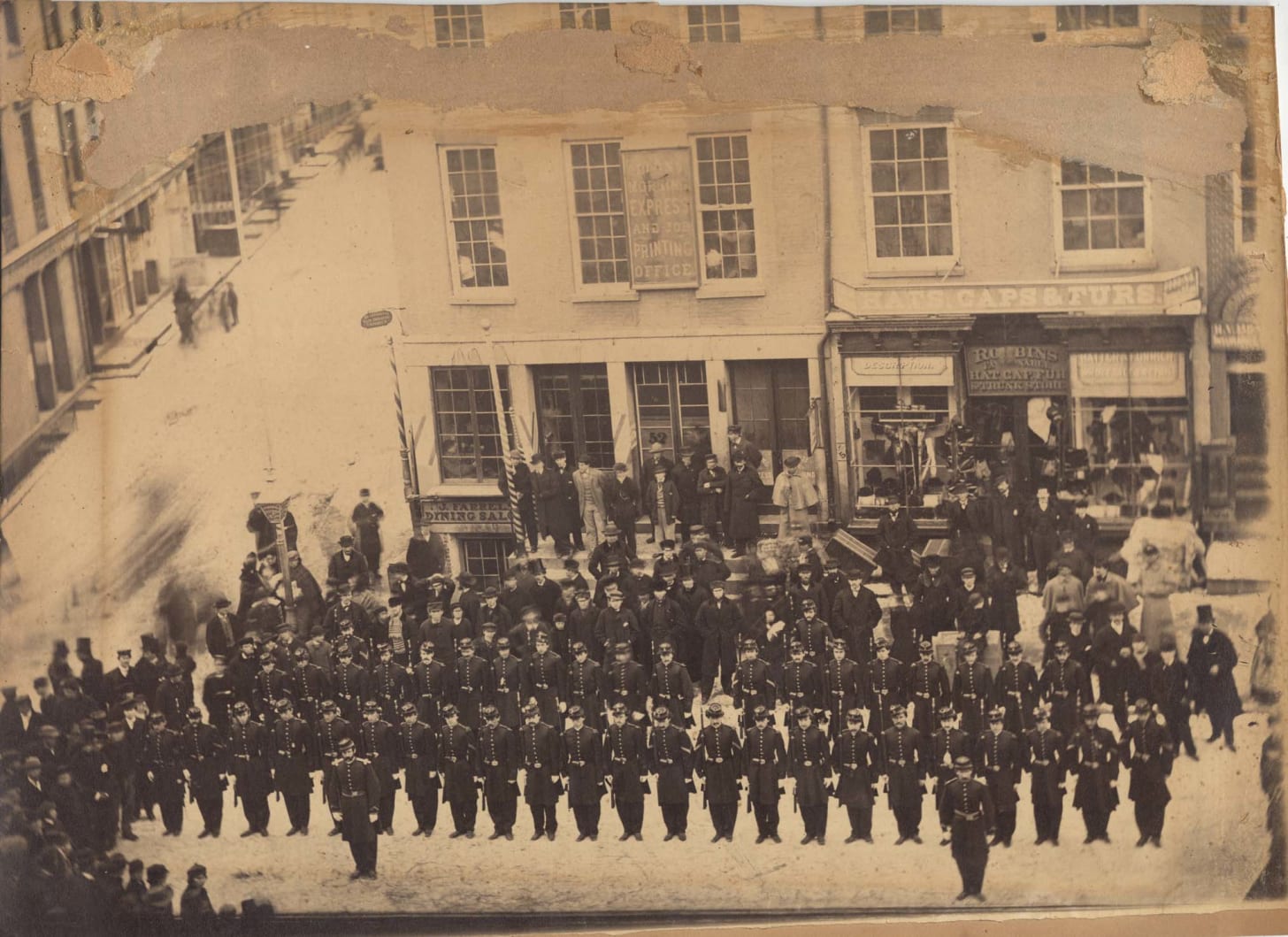

But searching just a little bit longer I found another photo on the website of the New York State Military Museum, labeled "Company of 10th NY Inf on State and Green St, Albany NY 1864." It’s still about 18 years after Twitchell painted Melville’s portrait, but this looked even more promising. But how to determine which corner, exactly, the 10th Infantry was standing on?

If you zoom in on the building, you can make out several words on the signs. Most notably “HATS CAPS & FURS” and the name “Robbins.” And there in the 1864 Albany City Directory I found “Robbins John S. hatstore, 54 State.” Just for good measure, I also tracked down the location of the J. Farrell Dining Saloon, the below ground level restaurant right at the corner, as being at 52 State Street, making this precisely the southwest corner of State Street, running horizontally, and Green Street, running vertically on the left.

Twitchell’s studio from1847 is… well, it’s almost in this photo, in that sliver of a building at the far right. Walking up that small set of stairs, Melville would have had the Albany State Bank where he worked as a young teenager half a block to his right, and Stanwix Hall just around the corner to his left.

You can see the whole corner in this photo from 1940, with Keeler’s looking just as it did four decades earlier.

An Unlikely Gam — Dr. James Armsby

Among Twitchell’s long list of impressive patrons in Albany was Dr. James H. Armsby, co-founder of the Albany Hospital and the Albany Medical College where he was a popular professor of anatomy, physiology, and surgery. Armsby, aside from being a working physician and one Albany’s most important institution builders in the 19th century, was also a patron of the arts, “especially of young chaps who were in their first struggle" one benefactor of his patronage later remembered.

Shortly after completing Melville’s portrait, Twitchell received a commission from Dr. Armsby to paint a portrait of his son Gideon, then about nine years old. The job was yet another example of the parade of commissions Twitchell earned from the Albany elite, leading to who knows how many more requests.

This tangled web of influence caught up with Melville just a few years after his own portrait was made, then living as a newly-married man in New York City. In October 1849, Herman sailed from New York to London to find a publisher for White-Jacket, making the acquaintance of many fellow passengers along the way. In a comical scene recorded in his journal — and evidence of his growing fame — on the ship’s first full day at sea Melville spotted a woman reading Omoo on deck. “Now & then she would look up at me,” he wrote, “as if comparing notes.”

The woman, he wrote, was “the wife of a young Scotchman, an artist, going out to Scotland to sketch scenes for his patrons in Albany,” identified in the Northwestern-Newberry edition of Melville’s journals as the painter William Hart. Hart later introduced himself to Melville as an acquaintance of Asa Twitchell, who had evidently mentioned his portrait of the rising literary star.

Though born in Paisley, Scotland, Hart had moved to Albany with his family in his early youth, and like Twitchell got his start decorating carriages. After several years traveling the country painting landscapes, Hart began exhibiting his work at the National Academy of Design in 1848 and attracted the attention of none other than Dr. James H. Armsby, philanthropist to Albany’s young artists, who sent him on a three-year voyage back to Scotland to paint landscapes of his homeland. (Incidentally, Hart later became the grandfather of children’s writer E.B. White, author of Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little — of no import here but still a remarkable connection.)

When Armsby died in 1875, his students honored him with a memorial in Albany’s Washington Park, a tall pillar supporting a bust made by sculptor Erastus Palmer, the other old man in the photo I shared last week and a close friend of Armsby’s as well.

What does this all mean? Absolutely nothing! Just a fascinating peek at the surprisingly vibrant artistic scene in Albany, New York in the 19th century!