Images of Melville, Part 1

; or, a peep at the portrait by Asa Weston Twitchell

There aren’t many things I have in common with Herman Melville. I don’t really care for wide open seas or rural New England; I’d be hard-pressed to jump ship on a remote Pacific island and just hope for the best; and poetry — especially 18,000 lines of it at once — is not my jam. But we do share one notable characteristic: we both absolutely loathe having our picture taken, much to our families’ chagrin.

Of course, no one is completely in control of their image, and even Melville was badgered into having his portrait painted or photograph taken once in a while throughout his life. In the end, the world was left with just eight known images of him, the first a portrait made in his late 20s, the last a photograph taken just a few years before his death.

Although you’ve probably seen them all (or at least nearly all), like so many other parts of Melville scholarship, influence, and memorabilia they’re often taken for granted, the same handful of images on countless dust jackets and glossy photo inserts. But I had a hunch that there was more to learn about these images, so over a series a posts I’m going to spend some time looking at each one to see what I can find out about their circumstances, the painters/photographers, where Melville was in his life and career, and what led Melville to begrudgingly consent to them.

We’ll begin at the beginning and work our way forward, opening the series with a portrait made at about the height of his fame.

#1. An oil painting by Asa Weston Twitchell, c. 1846-1847

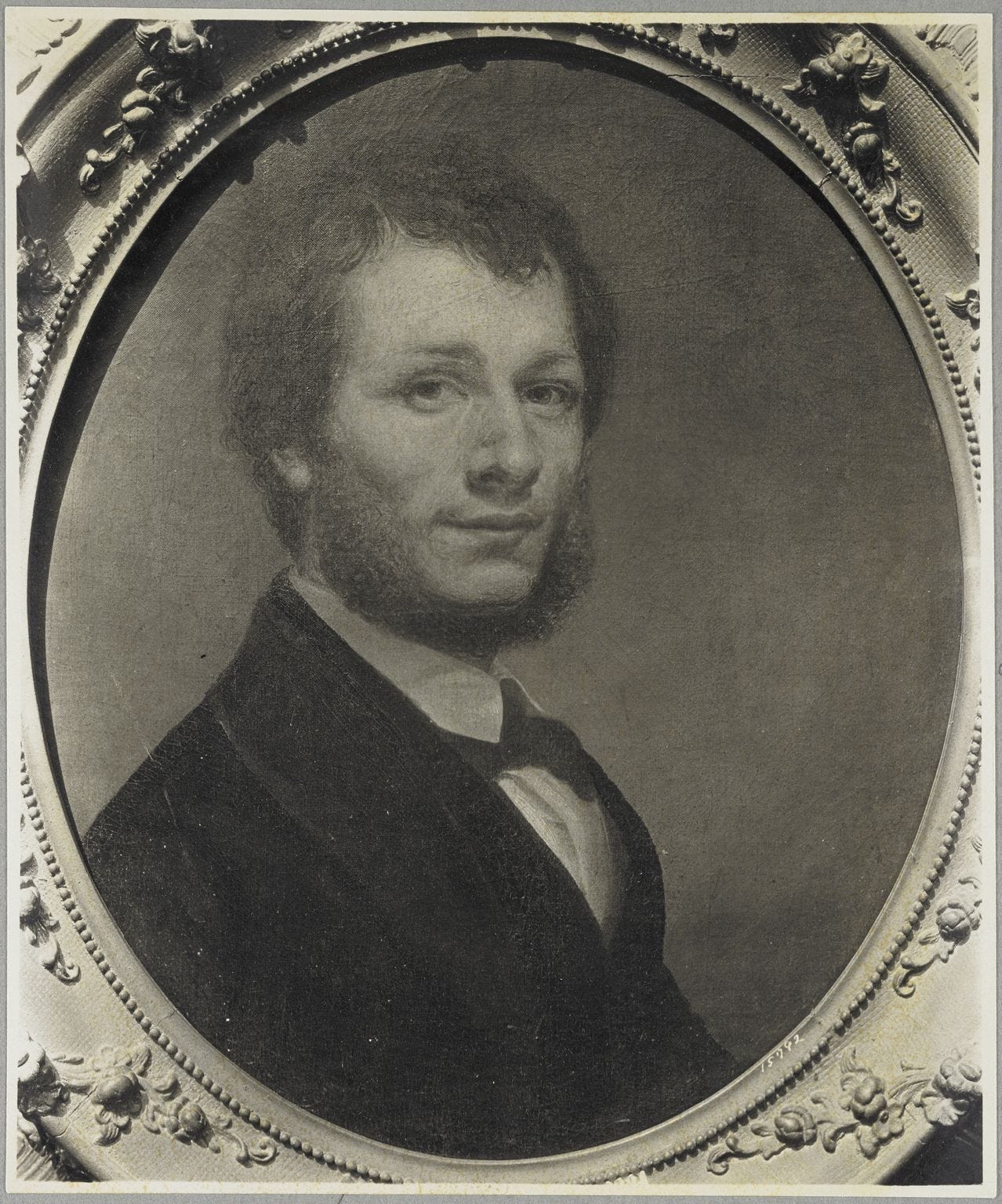

The first known image of Melville is a portrait by artist Asa Weston Twitchell showing the author at about age 27, rosy-cheeked and wearing a bow tie and an almost Ahabian beard. It’s an image I’m sure you’ve seen a thousand times.

Morris Star, in a checklist of images of Melville published in the Bulletin of the New York Public Library in 1967, wrote of the portrait:

Painted full face, the portrait at bust length presents a youthful Melville, in his late twenties, with abundant, wavy hair and a short, tidy beard. Unlike his appearance in all of his later representations, here he has no mustache. The straight nose and the mouth are delicately modeled, and the glance at the observer is unconcealed and guileless.

This is about the most anyone’s really cared to say about the portrait itself so far as I could find in the Melville literature, and even the circumstances of its creation seem to be a matter of no great interest. It’s been dated anywhere from 1845 to 1847 and virtually nothing has been written about Twitchell, whose virtuosic career spanning almost the 19th century has been largely forgotten outside of certain galleries and the state capitol complex in Albany, New York.

But let’s begin with Melville, contextualizing the portrait in time and place where we find him riding a wave of success as an author but, more critically, having finally found a job that would get him out of Lansingburgh.

“The Unemployable Herman Melville”

When Melville sat for his portrait, it’d been about two years since he’d returned from his years at sea. He’d left to go whaling in January 1841, jumped ship at Nuku Hiva in the summer of 1842, and then slowly made his way back via whatever ship would take him closer to home, finally arriving in October 1844.

“Home” at the time was neither in Manhattan where he was born in August 1819, nor Albany where his family moved in October 1830, but Lansingburgh, New York, a hamlet on the Hudson River about 12 miles north of the capital, population ~3,300. It was the final and most desperate stop on the family’s downward financial slope in Herman’s early childhood. His father Allan was an importer of French goods, buying and reselling items such as scarves, handkerchiefs, colognes, and belts to upscale New Yorkers, but depended on large sums of borrowed money to balance his books and keep up appearances with a several servants at home. When his debts finally caught up with him in 1830, he sold off his remaining assets and moved the family to Albany where his wife Maria’s rich — though stingy — family coincidentally lived.

Two years later, Allan was dead (pneumonia, delirium) and left his family in desperate financial straits. Maria survived by begging for handouts from relatives and mortgaging small parcels of inherited land. Herman was pulled from school and sent to work at the age of 12, first as a clerk at the New York State Bank (secured through the help of his Uncle Peter, a bank director), and later helping out at his brother’s cap and fur store.

Neither his nor his brother’s contributions were enough to keep them afloat in Albany, however, and in May 1838 the family moved to even cheaper accommodations farther up the Hudson River. Although Lansingburgh was one of the nation’s first planned communities, and arguably punched above its weight with several schools, churches, and hotels, Herman would have had far fewer economic or social opportunities than he did in Albany. Melville biographer William Gilman writes that Melville, about to turn 19 years old, “endured the pangs of exclusion” with the move.

Lansingburgh had few resources of the kind that Albany offered—no theater or museum, no musical society except a church choral group, and only small public libraries. Two young men’s clubs held weekly meetings, read essays, and conducted debates, but Melville could not have paid the membership dues. In all probability, he endured the pangs of exclusion from the normal social pursuits of his contemporaries, which only a year before had been readily available for him. As for economic opportunity, Lansingburgh had little to offer. It boasted a few manufactures and a considerable trade in grain and lumber, but its location well beyond the navigable depth for steamboats had already doomed it to gradual decline as a river port.

Instead, he took engineering and surveying courses at the Lansingburgh Academy, tried and failed to get a job in with the Erie Canal (again leaning on family connections), and wrote love poems to his crushes.

It was this period of his life which biographer Hershel Parker refers to him as “The Unemployable Herman Melville,” moping around town and getting on his family’s nerves. In May 1839, The Unemployable’s older brother Gansevoort persuaded him to get out from under his mother’s wing, leaving sleepy Lansingburgh, and find work as a greenhand aboard a merchant ship. If his reminiscing in Redburn is anything to go by, it was a humbling and even humiliating experience, even for the under-educated and inexperienced Melville.

Then I was a schoolboy, and thought of going to college in time; and had vague thoughts of becoming a great orator like Patrick Henry, whose speeches I used to speak on the stage; but now, I was a poor friendless boy, far away from my home, and voluntarily in the way of becoming a miserable sailor for life. And what made it more bitter to me, was to think of how well off were my cousins, who were happy and rich, and lived at home with my uncles and aunts, with no thought of going to sea for a living. I tried to think that it was all a dream, that I was not where I was, not on board of a ship, but that I was at home again in the city, with my father alive, and my mother bright and happy as she used to be. But it would not do. I was indeed where I was, and here was the ship, and there was the fort. So, after casting a last look at some boys who were standing on the parapet, gazing off to sea, I turned away heavily, and resolved not to look at the land any more.

Prospects weren’t much better when he returned to Lansingburgh that fall. Once again he turned to relatives asking for help landing a job, traveling as far west as Galena, Illinois to beg his Uncle Thomas for work, and once again he came away empty handed. So having little or no money in his purse, and nothing particular to interest him on shore, Herman went a-whaling.

When he returned to his family’s home in Lansingburgh late 1844, Herman, now 25 years old, regaled friends and family with stories of his time at sea. With their encouragement, he began to compile the stories into a thinly-veiled narrative, scribbling out a draft of Typee over the summer of 1845. With assistance again from his brother Gansevoort, the book was published early the following year.

Typee was an overnight success, selling nearly 4,000 copies in its first year and making a small phenomenon out of Herman Melville, the “man who lived among the cannibals.” (One can only imagine the cognitive dissonance of becoming known worldwide for such adventurous feats while living with his mother in the outskirts of Albany). But for all the fanfare, he was also just $400 richer.

That summer, with a small taste of fame and the possibility of getting out of Lansingburgh, Melville promised his publisher a follow-up to Typee and delivered a draft of Omoo in mid-December. At the same time, Herman was courting Elizabeth Shaw, daughter of the Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. Omoo was on bookshelves in the spring of 1847; he and Lizzie were married in August.

Herman had proven himself employable — or at least marketable — and it was time, it seems, to celebrate the moment by committing his likeness to paint. It not only marked his and perhaps his family’s reintroduction into proper society, but was also undoubtedly a great relief that he simply had a job.

Asa Twitchell at the Crossroads

On the other side of the easel that day was portrait artist Asa Twitchell. Although there’s no biography of Twitchell, no catalog raisonné, no archives of his records and correspondence, and hardly any significant background information about him online, I was able to piece together his life history from dozens of fragments scattered in 19th century newspaper articles, clips from old “Who’s Who” reference works, histories of of Albany, and even biographies of his subjects. Twitchell, I learned, was not an established artist but a close peer, possibly even an acquaintance, on a curiously similar trajectory in that moment. The future looked bright for both young men, though they would experience very different levels of success and recognition in their lifetimes — and then profoundly different levels of recognition in the century to follow.

Asa Weston Twitchell, Jr. was born in Swanzey, New Hampshire on January 1, 1820, four months to the day after Melville. His father, Asa Sr., was a wheelwright and wagon maker from nearby Dublin, New Hampshire whose ancestry in America dated back to Puritan immigrants arriving in the 1630s. The hills and mountains in the region, notably Mount Monadnock just to the town’s south, formed some of Asa Jr.’s earliest memories and would inspire him as an artist throughout his life. This was, incidentally, the same peak that the mountain-obsessed Melville would use to describe the white whale with its “great, Monadnock hump.”

“From the first he had the soul of an artist,” said one particularly flowery profile of him written in his later years, and “could not recollect the time that he did not want to make pictures.” Drawing in pencil as a young boy, he found he had a natural aptitude for capturing faces and expressions. But it wasn’t until he was about ten years old that he had his first real exposure to art. Evoking a moment straight out of The Spouter Inn, young Asa was traveling with his father on business when he saw three portraits on the wall of a village hotel in Vermont. The paintings left him “spellbound” and “determined to be a portrait painter.”

He never took a lesson in drawing or painting, and what he learned he acquired himself from observation or else it came natural to him. When he was very young, possibly ten years old, his father took him to a village hotel in Vermont, at a place where the former had business. It was in this hotel that Twitchell first saw a portrait. There were three of them, crude paintings they may have been, but to the young artist they were the most wonderful works of art. He was spellbound and gazed at them for hours… The oil paintings awakened his genius and from that time he was determined to be a portrait painter. He returned home and continued making pencil sketches.

The prospect of lessons or even encouragement, however, was off the table. Asa’s father “frowned on his son’s inclination to become an artist,” insisting he follow in his footsteps as a wheelwright. As a concession, he was allowed to decorate his father’s carriages and do ornamental work — a bargain bound to backfire. As his work was paraded through the towns New England, people inevitably remarked on the designs and began asking for his help with skilled painting jobs. Asa Sr. grumbled through the compliments.

When Asa, oldest of the three children, was about 18 years old, the family moved 100 miles west to Lansingburgh, New York — the same year that Herman’s mother Maria moved her own family there from Albany. The Melvilles lived at the corner of North and River Streets; the Twitchells bought a home about a mile north. And while it’s hard to imagine that the two never crossed paths, I didn’t come across anything suggesting that they did. Herman, at least, was involved in several youth organizations, and even performed as Shylock in a high school production of the Merchant of Venice; Twitchell’s extracurricular activities at this time are less clear.

In 1839, just as Herman was resigning himself to a life at sea, Asa was getting his official start as a portrait artist against his father’s protest. His first sitter, a deacon in the Baptist church called Old Father Goewey, was known for his “generous and large nose,” captured in the portrait much to the minister’s delight. “The good deacon was tickled very much with his picture,” said Asa many years later, and threw his hands up in amazement: “‘Old Father Goewey, as I live,’ he exclaimed.” Goewey “commenced to shower praises on young Twitchell in his father’s presence, and, not a little to the latter’s displeasure,” insisting that Asa “possessed great talent, which should be cultivated and encouraged.” Asa Sr. finally relented, and from that moment supplied his son with any materials he needed.

Naturally, one of Twitchell’s first works in oil after Goewey was a self-portrait, completed at around age 19. He later reflected that his craft at this time was clearly still in need of the development, but he at least proved to himself that “he knew how to get a likeness.” [Note: Though the painting is now officially “unlocated,” the Frick Art Museum has this black and white photo taken in the 1930s before it was sold to a private collector.]

Another early sitter for a portrait was Nancy Simons of nearby Schaghticoke, New York, who Asa married in Lansingburgh in 1841.

In fact, Asa and Nancy were married on January 3, 1841, the exact day that Melville set sail on the Acushnet to go whaling and rid himself of his nervous hypos. On a very different track from the wandering Herman, the couple had their first child in October.

Far from unemployable, Asa’s innate talent won him an almost effortless stream of commissions and accolades, ingratiating himself among the leaders of Lansingburgh and beyond. The Troy Budget newspaper ran a notice in November 1842 typical of his career after his painting was selected to be exhibited at the Rensselaer County Fair, “recommend[ing] him to the generous patronage of the friends of the fine arts.”

And recommended he was. In 1843, Twitchell moved to bustling Albany by Constable George Brainerd, who commissioned portraits of him and his wife, even offering up his own home while the newlyweds sought their own place in the city. Once settled, Asa’s career continued to flourish — as did his family, which eventually grew to include nine children — and he “soon had among his friends the most prominent Albanians, and most of them engaged Twitchell to paint their portraits.” Per the Albany Argus, he never lacked for commissions, having “always from 40 to 50 portraits on hand to paint.”

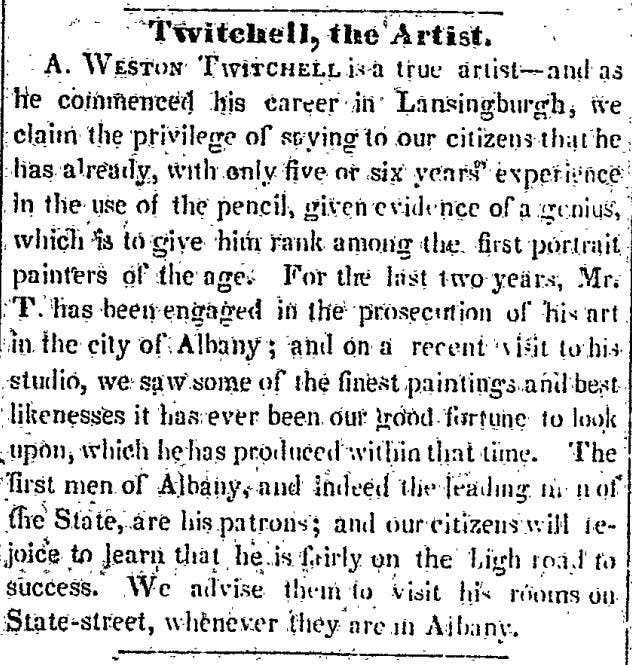

Despite Asa’s head start, by 1846 he and Herman were both experiencing well-deserved success in their respective fields. Just as Typee was hitting bookshelves, the Lansingburgh Gazette included a proud notice of for former Lansingburgh native’s thriving career over in Albany.

Later that year Asa began showing his work at the National Academy of Design, and eventually earned admission to the prestigious association with a portrait of Dr. T. Romeyn Beck, principal of the Albany Academy — Herman’s alma mater.

It was about this stage of his career when Asa met Herman, but suffice it to say that for the next 60 years, Twitchell was an integral part of the fabric of Albany’s upper echelon, the go-to portrait artist for prominent city and state leaders, politicians, judges, religious figures, professors, and anyone else able to foot the bill. He’s said to have painted more governors of New York than any other artist, made notable portraits of Abraham Lincoln, Judge Rufus W. Peckham, and countless other distinguished men of his era. At his death, Twitchell was considered “the dean of Albany artists,” an impressive group of painters and sculptors which included close friends such as Erastus Dow Palmer, Charles Loring Elliott, William Hart, and Homer Dodge Martin.

But in his later years, perhaps due to the prevalence and ease of daguerreotypes, Twitchell turned his attention to landscapes, revisiting the pastoral scenes of his youth. “I find myself going back to the memories of my childhood,” he said. “I was born in New Hampshire, and my first memory is of the New Hampshire hills…. I have gone back to the little New Hampshire village that belonged to my childhood memories, and I have tried to paint some of those hills and valleys.”

He was still hard at work until his death in April 1904 at the age of 84. A profile published by the Argus just days before his died found his studio full of paintings of hills, skies, and streams. “Mr. Twitchell still paints his portraits, and good ones too,” the paper reported, “but as a matter philosophy and poetry he spends his happiest hours in his studio among his hills, painting toward the horizon line.”

A Wild Melville Appears

Going back to that day in late 1846/early 1847, things were looking up for both young men. Herman had easily sold Omoo to publishers in London and New York — without his older brother’s help this time — and received generous offers on both sides of the Atlantic. Meanwhile, the “first men of Albany” were lining up at Twitchell’s door for their turn to sit for the young prodigy, said to be "on the high road to success."

Herman would have felt right at home walking into Twitchell’s studio, then located on State Street at the center of Albany’s buzzing downtown. They were the same streets where he spent practically his entire adolescence from age 11 to 18, and where his mother’s side of the family were practically royalty.

The Gansevoorts had lived and thrived in Albany since Harmen Harmense Van Gansevoort came from Holland in the mid-17th century. Harmen, a master brewer, founded a brewery in the Dutch (and later British) settlement, and became a wealthy and important man in the city in the process. For his efforts in defending the city from Leisler’s Rebellion (in which a militia seized control of the southern part of the New York colony) he was rewarded with large tracts of land along the Hudson river, and was later appointed a justice of the peace. When Harmen died in the early 1700s, he left his children a “baronial inheritance,” setting up generations of descendants to leave their mark and family name on the city of Albany.

The family’s legacy loomed even larger after Harmen’s grandson Peter Gansevoort became a hero of the Revolutionary War for defending Fort Stanwix from a British invasion storming south from Quebec. Gansevoort Street (once much longer than it is today) is named for Peter, but frankly could have been named for half a dozen other descendants. Peter’s brother Leonard, for instance, was a member of the New York State Assembly and Senate, and a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1788.

The next generation of Gansevoorts served in the state legislature and directors of various city and state institutions, but also made their own, more architectural mark on Albany that would have loomed large in Herman’s mind. In the 1830s, Peter’s sons (i.e., Melville’s uncles) built an enormous mall/conference center at the center of town, featuring shops, restaurants, offices, a two-story ballroom, and hotel rooms. Apparently at the town’s insistence they named it Stanwix Hall in honor of their father’s heroic war victory, topping it with an unmistakeable dome. (Herman’s second son was also named Stanwix in honor of Peter’s legacy).

In other words, important sites from Melville’s family and his own early life, including where he lived, studied, and worked were all clustered around the same area. Though he was no stranger to the city when he lived in Lansingburgh, returning to the area this time to have his portrait painted in honor of his success undoubtedly had a different feeling, finally worthy of the legacy surrounding him. On the map below, you can see just how packed the city was with his personal history — plus Twitchell’s studio on State Street just steps away from it all.

That said, what we know about the actual meeting between Melville and Twitchell essentially boils down to a single word, but it’s one which tells us something important about the arrangement: “gratis.” That is, Twitchell painted his portrait for free, and it’s not hard to deduce why: there was a lot of opportunity in getting to know this Herman Melville, and least of all because of his new bestseller. Rather, Melville had proudly declared his Albany bona fides in his dedication of Omoo, ‘cordially inscribing’ it to his uncle Herman Gansevoort, co-owner of Stanwix Hall.

(Typee was dedicated to his also very notable future father-in-law Lemuel Shaw, but a judge in Boston wasn’t of much use to a portrait artist in Albany)

The family connection also did not go unnoticed in local press. Even if Twitchell hadn’t seen the dedication page for himself, the Albany Evening Journal mentioned in its review of Omoo on June 25, 1847 that the author had “local habitation,” having resided in Albany for several years, and backed up his claim to be Herman Gansevoort’s nephew. (It was not a name to throw around lightly in the region).

What this suggests is that, in all likelihood, it was Twitchell who became aware of Melville’s family background and asked him if he would sit for a portrait — as opposed to Melville searching for an artist to celebrate the moment and coincidentally selecting the former Lansingburgh local. What better family to become acquainted with in Albany?

So, invitation in hand (we presume), Melville made his way down to Albany from Lansingburgh and found Twitchell’s studio at 56 State State. This watercolor vignette from 1848 shows the intersection of State Street and Broadway, about a block and a half east of Twitchell’s studio, humming with activity and with men dressed basically how Melville appears in the portrait, sans top hat.

We can also get a sense of what Twitchell looked like at the time from another self-portrait, undated but I would guess made in his late 20s or early 30s. (Like the others, this is a black and white photo taken around 1930; the original is “unlocated”).

The resulting portrait of Melville, oval in shape, measured approximately 25”x21” and was presented an ornate gold frame.

Unfortunately, Melville hated it.

Lost and Found

Well, that’s the legend anyway, but it does seem to be supported by the sad trail of provenance for the next 100 years.

Once the portrait was delivered to its sitter, it seems that it traveled with the family when they moved to New York City in October 1847, and again when they moved to Pittsfield, Massachusetts in September 1850. But when financial difficulties forced Herman to leave Arrowhead in 1863, he sold the property to his brother Allan. The portrait was left behind, allegedly hanging on a door as the story goes, and there it stayed for the remainder of his life.

Disregarded for decades, the painting became “blackened discouragingly by the years” and eventually fell into the hands of Allan’s granddaughter Agnes Morewood, who inherited Arrowhead through her parents. In fact, Herman’s own direct descendants seem to have been completely unaware of its existence, which would explain why Raymond Weaver’s 1921 biography of Melville (written with extensive assistance from Melville’s granddaughter Eleanor) wrote that the Twitchell portrait “is now not known to exist.” In reality, it was still collecting dust over in Pittsfield.

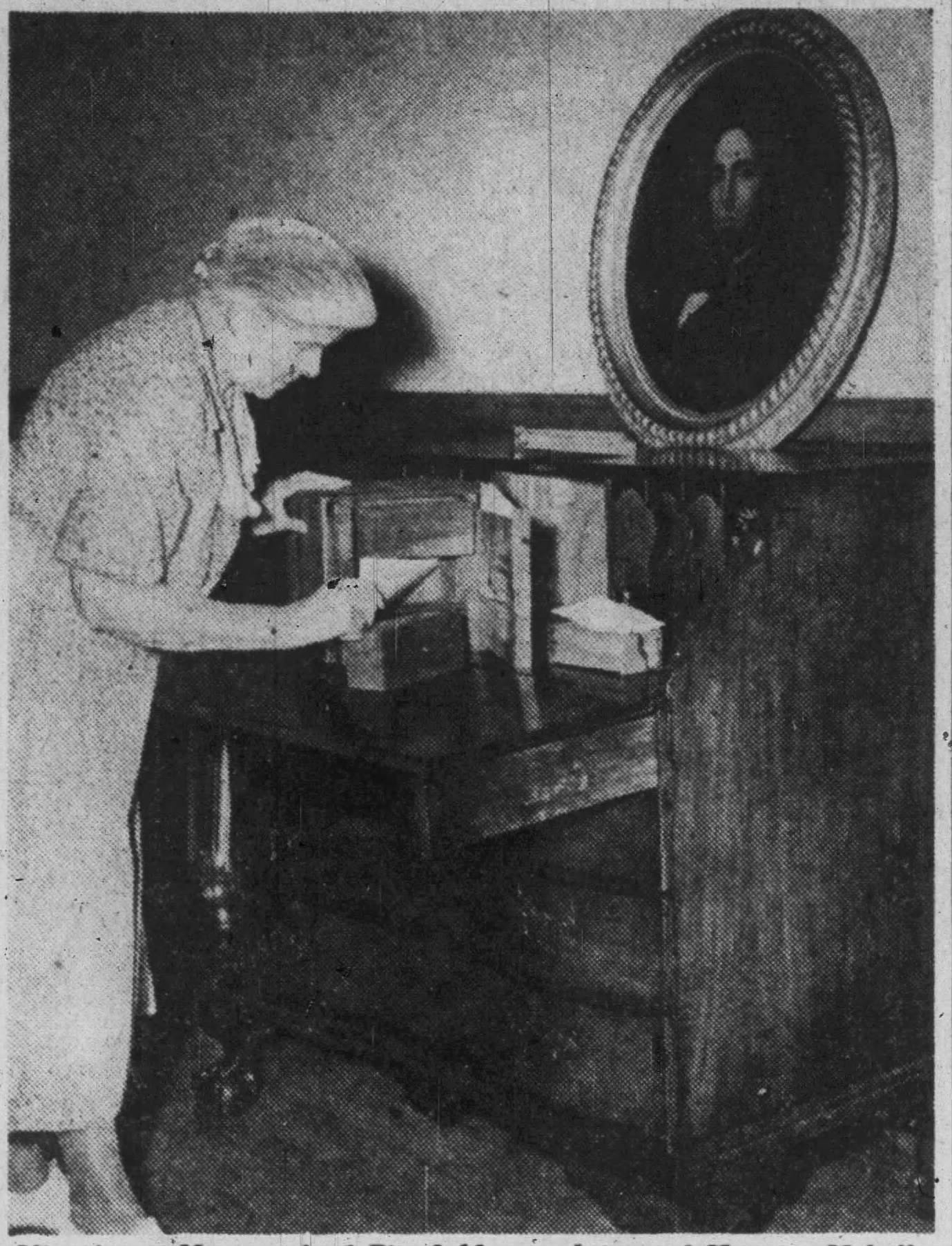

Perhaps it was around 1927, when the Morewoods sold Arrowhead to private owners outside the family that Agnes handed the painting over to Eleanor, family historian and keeper of the Melville legacy. Eleanor treated it to a skilled cleaning which “brought to light an interesting and colorful likeness.” She and her husband Henry hung the restored painting in their living room in Cambridge, Massachusetts, looking over her treasury of Melville memorabilia.

But where exactly the portrait came from was still lacking some clarity. While Eleanor may have assumed it was the missing Twitchell portrait mentioned in Herman’s journals and in Weaver’s biography, the portrait was unsigned. That mystery would only be solved decades later, when Eleanor joined the parade of newly-minted Melville scholars publishing books on the his life and work. In 1948, Eleanor edited an edition of Melville’s journal from 1849, and used the portrait as the frontispiece — the first time the portrait had been reproduced. She consulted for the occasion J.D. Hatch Jr., Director of the Albany Institute of History and Art, who definitively identified it as Twitchell’s hand.

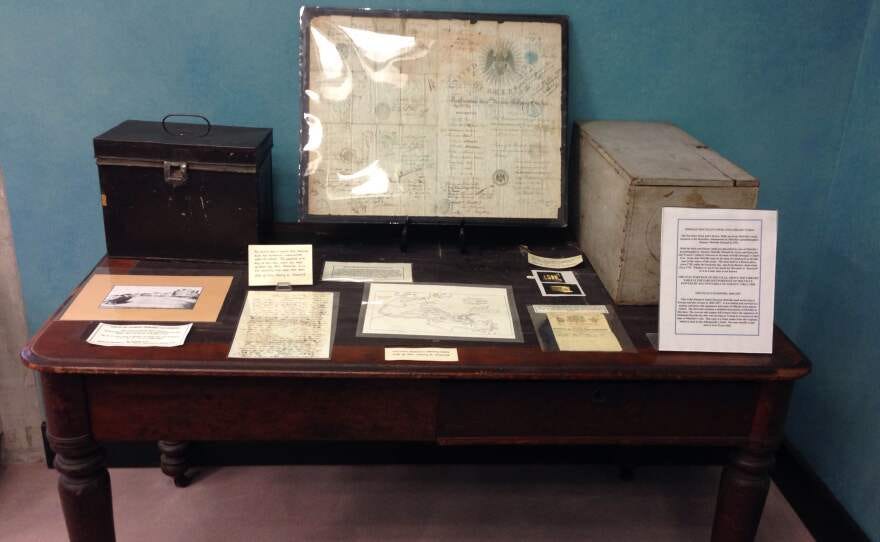

The portrait found its final home several years later in 1953 when Eleanor donated hundreds of items of Melville memorabilia to the Berkshire Athenaeum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, including not only the Twitchell painting but his writing desk, the Billy Budd bread box, his customs inspector badge, pipes, and more. The complete inventory was said to cover four typewritten pages.

In the photo below, printed in the Berkshire Eagle at the time of the donation, Melville’s grandniece Agnes Morewood stands in front of his desk and the Twitchell painting she found languishing behind a door at Arrowhead.

The portrait remains at the Berkshire Athenaeum to this day, where it remains a closely-guarded relic in the library’s Herman Melville Room. Unfortunately, the Athenaeum’s board of trustees insist that no photos are allowed in the room, so we can’t see exactly where it hangs today.

Just kidding! Thanks to this photo taken by a blogger just outside the room, we can see where it hangs just fine. Here it is right above Melville’s writing table, overlooking the Billy Budd breadbox and Melville’s 1856-57 passport.

And here again is the table, just to complete the picture.

Thanks & References

Thanks to Lansingburgh historian Warren F. Broderick Jr. (and in fact his entire family of Lansingburgh-area historians); Douglas McCombs at the Albany Institute of History and Art; and David Laczak at the Berkshire Athenaeum!

In addition to the links above, I relied on these (and many other!) sources to piece this all together.

Frances Broderick, “Local Artist Painted Melville's Portrait, Lansingburgh Voice, February 16, 1973

Warren F. Broderick, "Melville Family Properties as Revealed in Taxation and Assessment Records," Leviathan, Vol. 20, Number 3, October 2018

John Bryant, Herman Melville: A Half-Known Life, 2021

Catalogue of American Portraits in the New York Historical Society, Vol. 1, 1974

William H. Gilman, Melville's Early Life and Redburn, 1951

Peter Hastings Falk (ed.), Who Was Who in American Art, 1564-1975: 400 Years of Artists in America, 1999

Harold A. Larrabee, “Herman Melville’s Early Years in Albany,” New York History, Vol. 15, No. 2 (April 1934)

Jay Leyda, The Melville Log: A Documentary Life of Herman Melville 1819-1891 (2 Volumes), 1951

Minna Littmann, "Priceless Melville Papers Preserved in Bread Box," New Bedford Standard Times, October 14, 1951

Eleanor Melville Metcalf (ed.), Journal of a Visit to London and the Continent by Herman Melville: 1849-1850, 1948

Hershel Parker, Herman Melville: A Biography (Volume 1, 1819-1851), 1996

Erik Schlimmer, Cradle of the Union: A Street by Street History of New York's Capital City, 2019

Morris Star, “A Checklist of Portraits of Herman Melville,” Bulletin of the New York Public Library Vol. 71, No. 7 (September 1967)

You have a great talent for finding topics that have fallen through the ever-shrinkening cracks in Moby-Dick studies. Another good one here.

What an absolute treat of a read! I love the way it was pieced together. My sister has lived in three separate places mentioned here- who knew she crossed paths with these two. Looking forward to more!