[A special Tuesday edition of All Visible Objects — special in that I didn’t finish it in time for Sunday!]

Previously, I looked at what sea shanty the crew of the Pequod might have been singing when weighing anchor in Nantucket, a song which Ishmael tells us contained “some sort of a chorus about the girls in Booble Alley.” In short, although it had previously been identified as possibly being a song called “Haul Away Joe,” by connecting it more to the action — that is, the context of how the song was used to coordinate work — I found that it might actually have been another well-known shanty, “Sally Brown.” Or maybe Melville had neither song in mind exactly; they were singing some song about those girls, but the specifics don’t really matter.

But after all that research into the history of shanties, an equally important question remained: just what was Booble Alley, anyway? Where was it? And where, uh, did it get it’s name?

Melville Aghast

As I mentioned in that post, Booble Alley was slang among mid-19th century sailors for the red light district near the Liverpool docks. The city had become a major port over the prior 100 years, and with that growth came a huge population of sailors and workers in its various supporting industries such as ship builders, rope and sail makers, boarding houses, bars, and brothels. And to be clear, no matter where in the world your ship docked in that era, you were bound to step into what would have looked and felt like a familiar area, which all came to be known as “Sailortown.”

That said, the brief descriptions of “Booble Alley” in various annotated editions of Moby-Dick seemed to characterize it as being particularly depraved among all other Sailortowns in the world. Was this just mid-20th century squeamishness about drinking, drugs, and sex work, or was it really there more to it?

The best place to begin answering these questions is with Melville’s own experience in the area. In the summer of 1839, the 19-year-old Herman had just completed a term studying surveying and engineering at Lansingburgh Academy and was looking for a job. Despite a reference from his uncle Peter, a director of the New York State Bank, he failed to land a position working in the engineering department for the Erie Canal. Instead, the aspiring scholar glumly signed aboard the merchant ship St. Lawrence as a green hand for a round-trip voyage to Liverpool. The trip was his first experience traveling abroad, and first experience working as a hand on a ship, eventually providing him ample material his loosely fictionalized novel Redburn published a decade later.

The feeling of being forced into the life of a lowly sailor was bitter and solitary, and he felt especially sorry for himself as the ship first made its way to sea. As the sight of New York faded from view, he even recalled slightly dissociating from the experience.

Then I was a schoolboy, and thought of going to college in time; and had vague thoughts of becoming a great orator like Patrick Henry, whose speeches I used to speak on the stage; but now, I was a poor friendless boy, far away from my home, and voluntarily in the way of becoming a miserable sailor for life. And what made it more bitter to me, was to think of how well off were my cousins, who were happy and rich, and lived at home with my uncles and aunts, with no thought of going to sea for a living. I tried to think that it was all a dream, that I was not where I was, not on board of a ship, but that I was at home again in the city, with my father alive, and my mother bright and happy as she used to be. But it would not do. I was indeed where I was, and here was the ship, and there was the fort. So, after casting a last look at some boys who were standing on the parapet, gazing off to sea, I turned away heavily, and resolved not to look at the land any more.

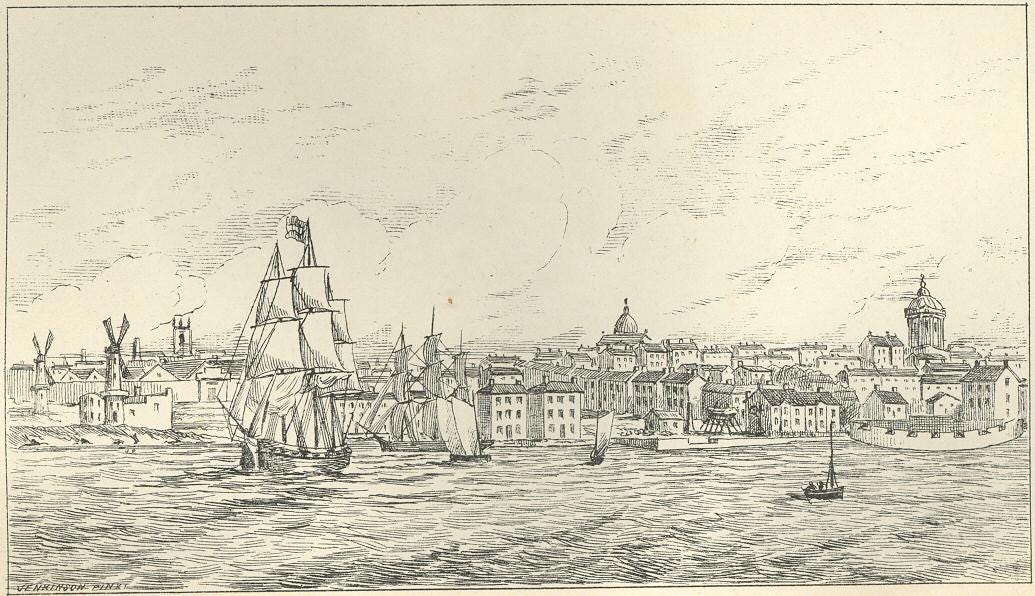

Throughout the voyage and its hard-earned lessons, Redburn is nevertheless excited to see another part of the world, all the while trying to “summon up some image of Liverpool, to see how the reality would answer to my conceit.” When he finally spotted land, “the fog, and mist, and gray dawn were investing every thing with a mysterious interest.” Alas, the city, he soon realized, looked like any other port city.

Looking shoreward, I beheld lofty ranges of dingy warehouses, which seemed very deficient in the elements of the marvelous; and bore a most unexpected resemblance to the ware-houses along South-street in New York. There was nothing strange; nothing extraordinary about them. There they stood; a row of calm and collected ware-houses; very good and substantial edifices, doubtless, and admirably adapted to the ends had in view by the builders; but plain, matter-of-fact ware-houses, nevertheless, and that was all that could be said of them.

To be sure, I did not expect that every house in Liverpool must be a Leaning Tower of Pisa, or a Strasbourg Cathedral; but yet, these edifices I must confess, were a sad and bitter disappointment to me.

Unfortunately, his disillusionment would only grow as he stepped into the streets and alleys of Liverpool’s Sailortown, overwhelmed by the oppressive squalor and misery experienced by much of the city’s poorest residents.

“The black spot on the Mersey”

Newton Arvin, in his 1950 biography of Melville, wrote that “there is not much doubt that the impressionable youth was precociously introduced to some of the ugliest possible aspects of human life” in Liverpool. Becoming a city of global economic importance in a relatively short amount of time went hand-in-hand with a rapidly growing population and massive spikes in immigration. Arvin paints a bleak vignette of the city at about the time Melville arrived:

He was pretty certainly introduced also to some of its blackest miseries. The Liverpool of the ’thirties had its genuine points of interest, but it had other sights, and these predominated, that could have inspired in a humane mind only a shuddering skepticism about the whole future of the society that tolerated them. The Liverpool that Melville saw was the Liverpool of the days that followed the hated new Poor Law… […] The great port was already in Melville’s time “the black spot on the Mersey,” and what it had to show him, rather more unforgettably than its Graeco-Roman public buildings, was the heart-sickening squalor of its working-class lanes and courts, its Rotten Rows and Booble Alleys, its cellar-dwellings and spirit-vaults, its beggars, its diseased children, its crimps and land-sharks and whores.

It’s worth pausing on one aspect of that description. As Arvin notes, Melville arrived in Liverpool — “the black spot on the Mersey” — five years after England had passed the New Poor Law, a far-reaching piece of legislation which fundamentally changed how the country dealt with its most impoverished citizens. Naturally, the main impetus for the act was to relieve the upper and middle classes of the tax burden to support the lower classes. In essence, under the new law the poor could only receive assistance if they moved into prison-like workhouses, earning a subsistence living in exchange for hard labor. Moreover, families would be segregated according to age and sex, while children might “find themselves hired out to work in factories or mines.”

Conditions inside the workhouse were deliberately harsh, so that only those who desperately needed help would ask for it. Families were split up and housed in different parts of the workhouse. The poor were made to wear a uniform and the diet was monotonous. There were also strict rules and regulations to follow. Inmates, male and female, young and old were made to work hard, often doing unpleasant jobs such as picking oakum or breaking stones. Children could also find themselves hired out to work in factories or mines.

Shocking exposés attempted to reveal the conditions of the workhouses — such as the Andover Workhouse Scandal, in which “half-starved inmates were found eating the rotting flesh from bones” — but the small reforms that followed did little to reign in abuses by the masters and matrons who oversaw them. Meanwhile, all other government assistance ceased, leaving people unwilling to enter the workhouse on their own.

In 1842, a government commission on the poor submitted its Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population and on the Means of its Improvement. The report, which the UK Parliament now calls “the most important 19th Century publication on social reform,” was innovative in its use of statistics to highlight variations in life expectancy and health outcomes as a result of class and occupation. In Liverpool, the commission estimated there were 40,000 people living in nearly uninhabitable cellars, and found that the average age of the 1,738 tradesmen and their families who had died in that year was just twenty-two. The average age of the 5,597 deceased laborers, mechanics, and servants was fifteen. Worse yet, 23 percent of children died before their first birthday, “or what it was in Geneva in the 17th century.”

In his time in Liverpool, Melville found that poverty was inescapable, presenting itself “in almost endless vistas” and to a degree he’d never seen at home.

For in some parts of the town, inhabited by laborers, and poor people generally; I used to crowd my way through masses of squalid men, women, and children, who at this evening hour, in those quarters of Liverpool, seem to empty themselves into the street, and live there for the time. I had never seen any thing like it in New York. […] In these haunts, beggary went on before me wherever I walked, and dogged me unceasingly at the heels. Poverty, poverty, poverty, in almost endless vistas: and want and woe staggered arm in arm along these miserable streets.

Nor was he alone in his observation. In a strange historical coincidence, in 1853 President Franklin Pierce appointed Nathaniel Hawthorne, his friend from college, as the United States consul in Liverpool. Hawthorne endured four years at the post, but unequivocally hated the “smoky, noisy, dirty, pestilential” city, “what with brutal ships’ masters, drunken sailors, vagrant Yankees, mad people, sick people and dead people.”

In one of the most memorable scenes in Redburn, the narrator hears a “low, hopeless, endless wail” coming from the cellar of an old warehouse on a street called Lancelot’s Hey just a block or so from the dock. Looking through a window he sees a starving woman and her children, “two shrunken things,” who barely have the energy to look at him when he calls to them. Appeals to authorities for help fall on deaf ears, and even after bringing them bread and water Redburn can only hope that they die peacefully. The experience left young Melville/Redburn in a morbid, disillusioned state, wondering:

Surrounded as we are by the wants and woes of our fellowmen, and yet given to follow our own pleasures, regardless of their pains, are we not like people sitting up with a corpse, and making merry in the house of the dead?

Melville in Sailortown

Such were the conditions in Liverpool in the summer of 1839. To find Booble Alley, though, we’ll have to focus more specifically on Sailortown. In Chapter 39 of Redburn, Melville describes a generally merry (if slightly chaotic) atmosphere there:

In the evening, especially when the sailors are gathered in great numbers, these streets present a most singular spectacle, the entire population of the vicinity being seemingly turned into them. Hand-organs, fiddles, and cymbals, plied by strolling musicians, mix with the songs of the seamen, the babble of women and children, and the groaning and whining of beggars. From the various boarding-houses, each distinguished by gilded emblems outside—an anchor, a crown, a ship, a windlass, or a dolphin—proceeds the noise of revelry and dancing; and from the open casements lean young girls and old women, chattering and laughing with the crowds in the middle of the street. Every moment strange greetings are exchanged between old sailors who chance to stumble upon a shipmate, last seen in Calcutta or Savannah; and the invariable courtesy that takes place upon these occasions, is to go to the next spirit-vault, and drink each other’s health. […]

In his 2011 book The Hurricane Port: A Social History of Liverpool, Andrew Lees adds vivid details about the experience of the transient sailors, such as what and where they might eat, drink, and spend their wages on. Although the vignette describes the area about 40-50 years after Melville first arrived, one doesn’t get the sense that it had changed all that much.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Liverpool had two main districts for visiting mariners. In the North End, Union Street and Brook Street, behind Princes Dock, were the focus, whereas the nearby older 'Sailortown' to the south still centered on Paradise Street, Hanover Street, Park Lane, Lower Frederick Street and Anson Terrace. Digs were run by seamen's wives, and the adjacent surrounding taverns, outfitters and ships stores were owned by ex-sailors. The shops sold greasy bacon, sweaty cheeses, potted herrings, hair oil and Epsom salts. Second-hand bric-a-brac stores offered up pictures of the Virgin, cracked crockery and scratched tables and chairs. Dinner for the crew consisted of boiled potatoes, beefsteaks, sausages, brawn, bread and pickle washed down with 'swipes', the lees of the beer barrels. […]

At any one time, there might be several thousand sailors chewing wads of tobacco and hanging around the Sailors' Home and Dispensary. The newly arrived, jovial and open-hearted five-minute millionaires, with their wads stuffed in their back pockets, were the kings of the town. The Blue Funnel and Booth sailors recently returned from Belém and Manaus often had a macaw or marmoset to sell in the Lord de Tabley pub in Park Lane. Some drifted down to the sailors' outfitters run by Jew Grossi in Paradise Street to exchange their advance notes for 75 per cent merchandise and 25 per cent cash or popped in to have their fortunes told by one of the many soothsayers.

However, this festive, rollicking scene obscures a far seedier and dangerous world just out of sight, which Melville (or rather, Redburn) introduces with a story about having watched police arrest a drunk sailor who had just murdered a woman at a bar. It’s in this unusually haughty rant where he first mentions Booble Alley among other “pestilent” zones, full of miscreants “bent upon doing all the malice to mankind in their power.”

This passing allusion to the murder will convey some idea of the events which take place in the lowest and most abandoned neighborhoods frequented by sailors in Liverpool. The pestilent lanes and alleys which, in their vocabulary, go by the names of Rotten-row, Gibraltar-place, and Booble-alley, are putrid with vice and crime; to which, perhaps, the round globe does not furnish a parallel. The sooty and begrimed bricks of the very houses have a reeking, Sodomlike, and murderous look; and well may the shroud of coal-smoke, which hangs over this part of the town, more than any other, attempt to hide the enormities here practiced. These are the haunts from which sailors sometimes disappear forever; or issue in the morning, robbed naked, from the broken doorways. These are the haunts in which cursing, gambling, pickpocketing, and common iniquities, are virtues too lofty for the infected gorgons and hydras to practice. Propriety forbids that I should enter into details; but kidnappers, burkers, and resurrectionists are almost saints and angels to them. They seem leagued together, a company of miscreant misanthropes, bent upon doing all the malice to mankind in their power. With sulphur and brimstone they ought to be burned out of their arches like vermin.

Booble Alley, Gibraltar Place, and “Rotten Row” are also where you’d find many Liverpool’s myriad brothels, estimated to have numbered around 1,000 by the 1860s. In fact, on the basis of criminal statistics, the city was “by some distance the capital of prostitution in Victorian England… far outstripping any comparable city.” (London had twice as many brothel houses as Liverpool, but was of course many times larger.)

Michael Macilwee, author of The Liverpool Underworld: Crime in the City, 1750-1900, explains that the city’s unusual number of brothels per capita was actually the unintended consequence of a law passed at the turn of the century forbidding fires and lights on berthed ships. Unable to cook meals on board as they would in other ports, Macilwee writes that sailors “were practically driven ashore in search of food, warmth and comfort.” The brothels were conveniently located “indecently close” to the bars, with “the joyful roar of sea shanties drowning out the moans of more illicit pleasures.”

What the city did have in common with other ports in this respect was that its main industries — and thus the majority of its job opportunities — catered primarily to men. Options for unattached, working class women were few and far between, and even rarer for the tens of thousands of women emigrating from Ireland escaping the Great Famine. Similarly, their male counterparts, if they couldn’t find work in the marine industries, often opted for the next best thing: joining the ranks of young men who formed gangs and swindled, robbed, and even murdered naïve green hands just like Melville who might be found wandering drunk in the alleys.

While virtually every book about Victorian era Liverpool discusses at length the lawlessness, temptations, and danger of the city’s Sailortown (Macilwee’s book is a fascinating read if you’re interested), I’ll leave it with another excerpt from Lees’ The Hurricane Port which I think captures what an alarming predicament a young, inexperienced Melville found himself in night after night for six weeks while waiting for the St. Lawrence to return to New York.

There were 600 houses of ill repute accommodating 2,000 mainly Irish harlots, including Harriet Lane, Blooming Rose, Jumping Jenny, Cast-Iron Kitty, 'The Battleship', Maggie May and Tich Maguire….

The sailors were united in their hatred of soldiers and scorn for landlubbers, and many carried daggers for self-defence against the dock gangs. The American and Nordic crews, often violently drunk, had a particularly tense relationship with the locals. The Cornermen, a posse of young Irish Liverpool toughs, hung around outside public houses to goad the sailors into a fight. Local brasses lured the foolhardy to Sebastopol, where North End High Rip pimps, in their distinctive bucco caps and mufflers, would roll the sailor over, leaving him battered and penniless in the narrow artery. Scuttles between rival gangs with the buckle ends of belts and daggers were common in the docklands. After a night on the tiles, the Icelandic whalers would often end up spread-eagled, stupefied and skinned naked in Lime Street. Some seamen disappeared forever, the victims of burkers or kidnappers in murderous no-go areas like Rotten Row and Booble Alley. […]

The Seaman's Friend Society, with its headquarters in the Gordon Smith Institute in Paradise Street, was founded in 1820 to keep sailors away from dishonest landladies and shanghaiers, and provide them with a cheap refuge in the Sailors' Home in Canning Place. Ironically, it was surrounded by the temptations of the Great Grog Palace, penny ale cellars and singing saloons like the Sans Pareil and the Liver, stuffed with animal trophies and coffee-coloured pictures of foreign ports. 'Gomorrah', with its brothels, boozers and brawls, was an irresistible draw for those who had jumped ship, the place where any sailor torn between two beautiful women could always encounter a third.

Finding Booble Alley

All of this background brings us to the original question: was Booble Alley a real place? A ‘nickname’ for a real place or area? Was it possible to figure it where it was? The first thing I noticed was that nearly every mention of Booble Alley that I could find was a reference to either Redburn or one of the two sea shanties mentioned earlier. Elsewhere, such as in Newton Arvin’s biography of Melville, I’d find it named alongside “Rotten Row” and “Gibraltar Place” without further detail, leading me to believe that these names have just became part of the vocabulary of old Liverpool, in large parts thanks to Redburn.

Beyond these texts, I looked through 19th century street directories, guidebooks for tourists, and scoured nearly a dozen contemporary maps looking for anything to help me pin it down. Ultimately, though, the most useful source by far was a book called Sailortown by Stan Hugill, who was also a critical source for learning about sea shanties. Although Hugill wasn’t born until 1906, his experience as a merchant seaman as a young man led him toward becoming a historian and recorder of the last days of the Age of Sail.

Along with hints collected from the various other sources linked above, I was able to use those old maps to piece together what and where Sailortown would have looked like nearly 200 years ago. The map closest in time to when Melville arrived (and also one of the more detailed, thankfully) was from 1836, Michael Alexander Gage’s “Trigonometrical plan of the town and port of Liverpool,” now in the collection of the National Library of Australia.

For example, if you zoom in to the area above Prince’s Dock, where Melville’s ship docked in 1839, you’ll see Lancelot’s Hey just to the north — the street where he encountered the starving woman and her two children. (Technically the direction is more like southeast, as this map is oriented about 90º counterclockwise). What Melville called “Gibraltar Place” was also a real location — actually Gibraltar Row — located on the other side of Prince’s Dock between Great Howard Road and Waterloo Road (which itself featured no less than 16 public houses).

James Stonehouse, in his 1848 “Handbook for the Stranger in Liverpool,” also mentions places like Atherton Street, "a low dirty street communicating between South Castle Street and Paradise Street;" Addison Street, "another low street;" and Bansatre Road, which he deems “not a very respectable locality.” (Note: all linked street names will go to a map centered on those places)

But, again, the real bounty came from Hugill’s book Sailortown, which simply explodes with details from that era including names of streets, bars, and boarding houses, and reported antics of specific street gangs. For each town Sailortown he examines (Liverpool is only one among many), Hugill builds an intricate map of an area that most accounts of Liverpool from the time would prefer to ignore and forget. Though this excerpt is long, I recommend at least scanning to get a sense of the detail:

Taverns and grog-shops to meet the growing need sprang up near the docks. In the Goree area, alongside St. George's Church in Derby Square, and near the Pier Head, harlots soliciting seamen were a common sight. Many of these girls were Irish, but a sprinkling of foreign harlots were also plying their trade around the waterfront by this time. […]

This spread, roughly, from Lancelot’s Hey and its surrounding alleys and rows, through Castle Street and the back streets around Wapping, to Park Lane and Paradise Street, reaching as far as the lower end of Parliament Street and its neighboring side-streets. […]

Liverpool’s Sailortown sprawled over a large area, its tentacles stretching even farther as the line of docks grew, and steam became a more important factor…. Starting from the area of the Canning, Salthouse, King’s, and Queens’s Docks one section covered, at different times, all the streets near here: Wapping, Canning Place, Paradise Street, Cleveland Square, Park Lane, Frederick Street through to Lower Parliament Street, and all the side-streets, alleys, courts, heys, weints, and ‘jowlers’ of the neighborhood as far as those around the Brunswick Dock. It also included the Duke and Hanover Streets area with some sailor boarding-house streets being found as far across the city as those off London Road. Most of this area was known as the ‘South End’, a name it still bears even today.

Another section consisted of all the streets, courts, alleys, and back ‘jiggers’ in from Castle Street and Derby Square, the Pier Head, George’s Dock, and the Sailor’s Church district. It continued along New Quay, and the famous Union Street with its adjacent lanes and ‘heys’, and Waterloo Road, near the Prince’s and Waterloo Docks, as far as Great Howard Street and its environs. All this area was called the ‘North End.’ […]

In Melville’s time (the late thirties) the area around Prince’s Dock appears to have been the Sailortown of Yankee seamen ashore. […] Unlike today, this area in from New Quay was a mass of sailor taverns and low-class drinking houses. The streets around here were the favourite haunt of ballad-singers, carrying their long broadsheets high above their heads. Blowsy and frowsy women, with their raggedly dressed children hanging on to their long filthy skirts, rollicking merchant seamen, and vociferous street beggars wandered to and fro over the cobbles. It was a district of cheap boarding-houses sandwiched in between the cotton warehouses many of which remain to this day, although the boardinghouses have long since gone. Starvation and poverty stalked everywhere…. Running parallel with Union Street stood Rosemary Lane, another crummy passage full of sailor dives…. […]

Union Street was chock-a-block with sailor pubs and boarding-houses and was to the ‘North End’ Sailortown what Paradise Street was to the ‘South End’ sailor quarter. […]

Melville mentions another sailor pub in this area the Golden Anchor, situated not far from the Prince’s Dock, somewhere near the Old Fort area. Nowadays its name isn’t even remembered. Tramping through Booble Area, Rosemary Lane, Gibraltar Row, and another red-light quarter, Rotten Row—dens of vice where many a sailor-man disappeared and was never heard of again—one came to dozens of dirty narrow lanes, full of cheap boarding-houses, many of them, like pubs, having signs hanging above their doors: anchors, eagles, crowns, and windlasses. These lands led into Great Howard Street, another centre of sailor life.

The pavements and drinking dens of Great Howard Street would be crowded with men from the ships lying in the Nelson, Bramley Moore and Clarence Docks, and nightly the gutters were filled with broken bottles and out-for-the-count tars and beaches. Gin palaces were found in every adjoining street as far as Marybone. By the end of the forties it was a district of Irish slums; emigrants from Ireland coming across to Liverpool in droves at the time of the Irish Potato Famine.

I thought that perhaps I could at least triangulate where Booble Alley could have been, so I went ahead and highlighted all of these place names on the 1836 map (you can see a larger version here, also downloadable in order to zoom in closer). In all, I think it gives a clear sense of the dense network of the streets and alleys where sailors like Melville would be found in the 1830s and ‘40s.

But still, where was Booble Alley? The most intriguing hint came from Hugill, who mentions that it was “long since gone,” referencing the many fires and construction of warehouses that accompanied Liverpool’s arrival on the global economic scene.

Gibraltar Row-Melville calls it 'Place' and Booble Alley, long since gone, were the whore-house streets where roaming Yankee and other seamen spent their stored-up energy. […]

With the building of new warehouses and so on, much of this rat-infested, harridan-ridden area has been buried, and it certainly isn’t a residential district, even for the poorest, any more. In its time Lancelot's Hey, and the dwelling-houses of the neighbourhood suffered many fires, one of the worst being that of the year 1833.

Perhaps the map I was using was too new, then? I continued my search using on this map from 1807, and even one from 1768, but unfortunately came up empty.

But while Hugill gives me some confidence that Booble Alley might really have existed sometime in the late 18th/early 19th century, ultimately the problem in finding it might be that it really was just an alley. A different map, this one from 1847, shows an elevated panorama, as if drawn from a hot air balloon. From this perspective and level of detail, it’s easier to see not just the main streets and roads but the unnamed alleys between courtyard housing along Bath Street, for example, behind the dock.

If you want an especially trippy experience, check out this immersive, interactive digital recreation of Liverpool’s courtyard housing and alleys from the 19th century, complete with voice actors and 3D models of many of the objects you might find there. It’s not hard to believe that these alleys might not have an official name, but that those with certain purposes, shall we say, might acquire a well-known nickname.

Ultimately, we might need to keep in mind a different lesson from Melville with regards to Booble Alley and Rotten Row, spaces for sailors, risk takers, and other ‘unseemly’ characters that polite society would wish away. They’re “not down in any map; true places never are.”

Bootle, Neighbor to the North

As for the name Booble Alley (besides whatever other connotations the word might have in a red light district) I can again only offer highly-speculative guesses. One clue is that in some versions of shanties like “Haul Away Joe,” Booble is actually replaced by the name Bootle, as in:

Ah, talk about your Bootle girls, around the corner Sally

Oh, the Baltimore whores in purple drawers come waltzing down the alley…

While “Booble” may be long gone from maps, Bootle was (and still is) Liverpool’s neighboring seaport town to the north. Stuart M. Frank, writing in a 1985 article in the New England Quarterly noted their “phonetic and orthographic” similarity, and suggested that they might be one in the same.

Bootle is another Merseyside seaport (immediately adjacent to Liverpool and well known to sailors) that figures occasionally in sailor songs. The solo line of this latter variant is sometimes sung “… Booble girls," after Booble Alley. The phonetic and orthographic similarity of the two names, "Booble" and "Bootle," and their generic and geographic proximity in the sailor world of Liverpool explain their ready interchangeability in oral tradition.

In the same vein, there was even a Bootle Alley in nearby Manchester in the early/mid-19th century (directly in the middle of the map below).

Even more suspiciously is that according an article in the Manchester Courier, published December 7, 1850, there was at least one “place of questionable repute” in that same Bootle Alley.

On the other hand, according to a dictionary of Liverpool-area place names from 1898, the word “Bootle” simply meant ‘house,’ dwelling,’ or ‘village’ in Anglo-Saxon, and was interchangeable with the word “Bold.” And while this is as far as I’ll go with the reckless speculation, it might be worth noting that I did find a Bold Street on the 1807 map of Liverpool not far from the docks and several streets simply labeled “Roperies.”

Renegades, Castaways, and Cannibals

We may never be able to pin down the exact location of Booble Alley, or even determine whether it was ever a real place in Liverpool. But I think knowing this history gives just a little bit more depth to the many ‘background’ sailors aboard the Pequod — those who we only hear from only infrequently like Bulkington, Archy, and Cabaco, or even unnamed characters like the carpenter, “English Sailor,” or, most diminutive of all, “5th Nantucket Sailor.”

The central figures of the book are so idealized that it’s easy to forget that, in reality, crews of whaling ships were not comprised of captains speaking in Shakespearian monologues, pious Quakers, kingly “savages,” and philosophical green hands who would rather be in a library than a mast-head. Ishmael tells us in no uncertain terms that the crew was “chiefly made up of mongrel renegades, and castaways, and cannibals,” the same who might have frequented the back alleys of Sailortown (for better or worse), and who I’m sure would have been glad to sing about the women they met there.