While planning a trip to New York City this month, I naturally started thinking about potential Melville sightseeing stops around the city. For as much as he’s associated with New England and the sea, in reality he both came from and lived the vast majority of his life in the most urban of places, the “city of the Manhattoes.”

Traces of Melville can be found all around the city, delineating the four decades he lived there as a boy, as a suddenly successful writer still fresh from his adventures at sea, and, some years later, as a man who was forced to make the practical decision to walk away from his career as a writer and become a customs inspector along the wharves of the Hudson River.

Even the word '“traces” might be overstating it, though. All of the homes where he and his family lived were razed and built over long ago. Many of the piers he patrolled six days a week for 19 years receive no ships are now city parks filled with sunbathers on sunny days. All that’s truly left to see in 2025 is a plaque noting the former location of his home at 104 East 26th Street, where he lived from 1863 until his death in 1891, and his grave at the Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. Looking at it on Google Maps, though, I’m not sure which one is sadder.

But what’s worse than a dingy plaque (often hidden by scaffolding) is no marker at all, which is the case for what should be one of the most important stops on the Herman Melville trail: the exact spot where he was born.

Although the building and even the address have been erased from the map, Melville’s life began at 6 Pearl Street in Lower Manhattan, just across the street from the Battery and the shoreline of New York Harbor. Here’s its current-day location:

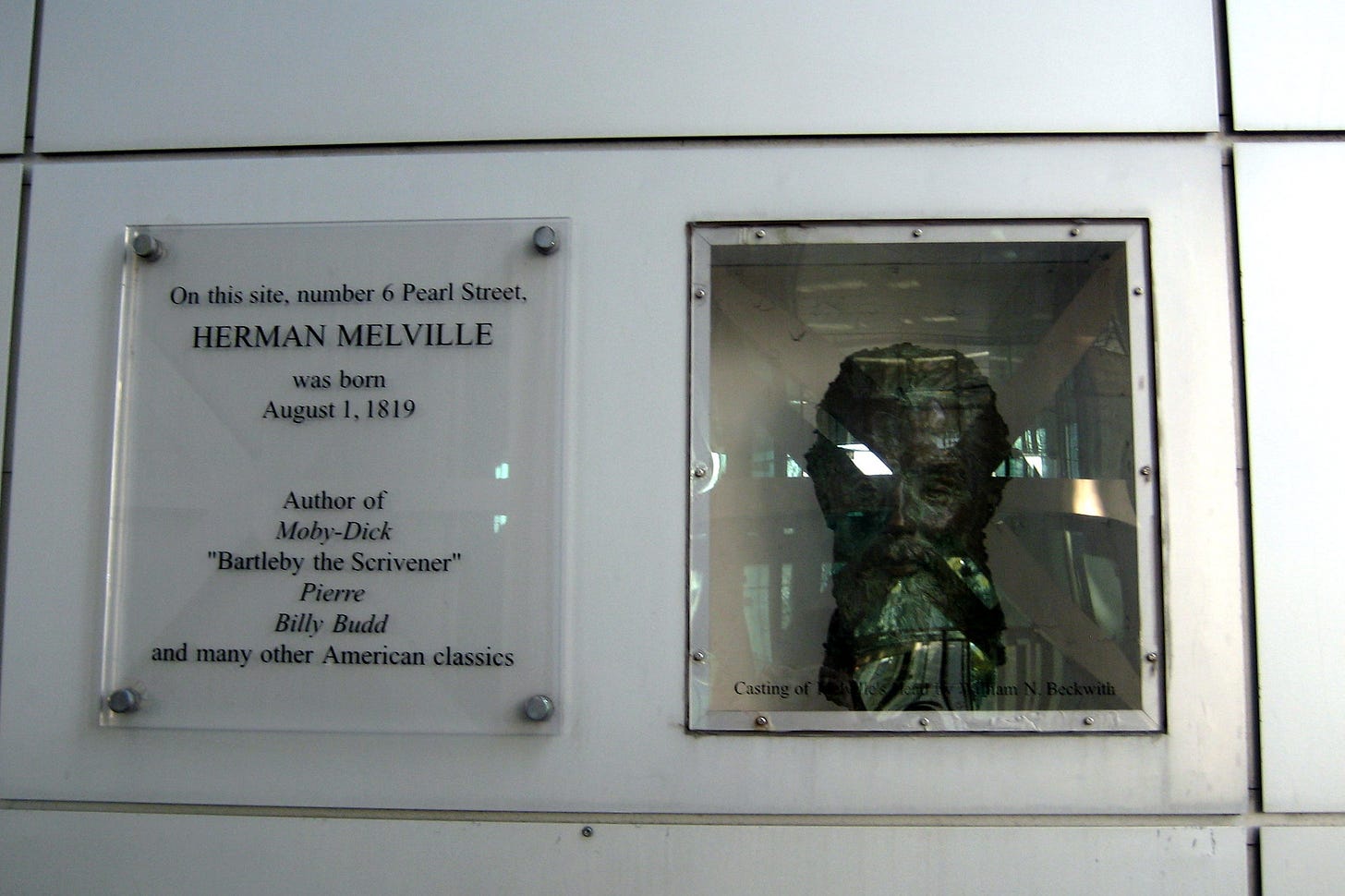

It hasn’t always been devoid of a marker, however. Until recently, Melville’s visage graced a small plaza on Pearl St. between two skyscrapers by way of a bronze bust with a plaque informing visitors that “On this site, number 6 Pearl Street, HERMAN MELVILLE was born August 1, 1819.”

Here’s a closeup from back in 2001, when poor Herman was looking a little sea sick.

To be precise, the plaque and bust weren’t attached to either building but rather were ensconced in/on a freestanding wall between them which marks the outer edge of the plaza. Not even a quarter of a mile from the shoreline, the bust faced the Hudson to the west, forever fixed in ocean reveries.

For many years, fellow water gazers from around the world came to this plaza to pay their respects, until suddenly it was gone; both the plaque and the bust were removed and replaced with a dumb blankness matching the rest of the wall, which is how it still looks today.

Melvilleans were aghast. Several members of the Melville Society Facebook page asked if anyone had seen the head. Some small efforts were made to locate it, but the security guards and cleaning staff they polled yielded little — or contradictory — information. Some said it had been damaged during Hurricane Sandy in 2012, while others remembered it having been stolen.

With my trip to the city looming, I recognized that this was a question for All Visible Objects (i.e., me) if ever there was one. It’s lamentable that the city has all but forgotten its connection to Melville’s life while Nantucket and New Bedford, places where he spent almost no significant time at all, have made cottage industries out of printing his name and fabricating little whale paperweights

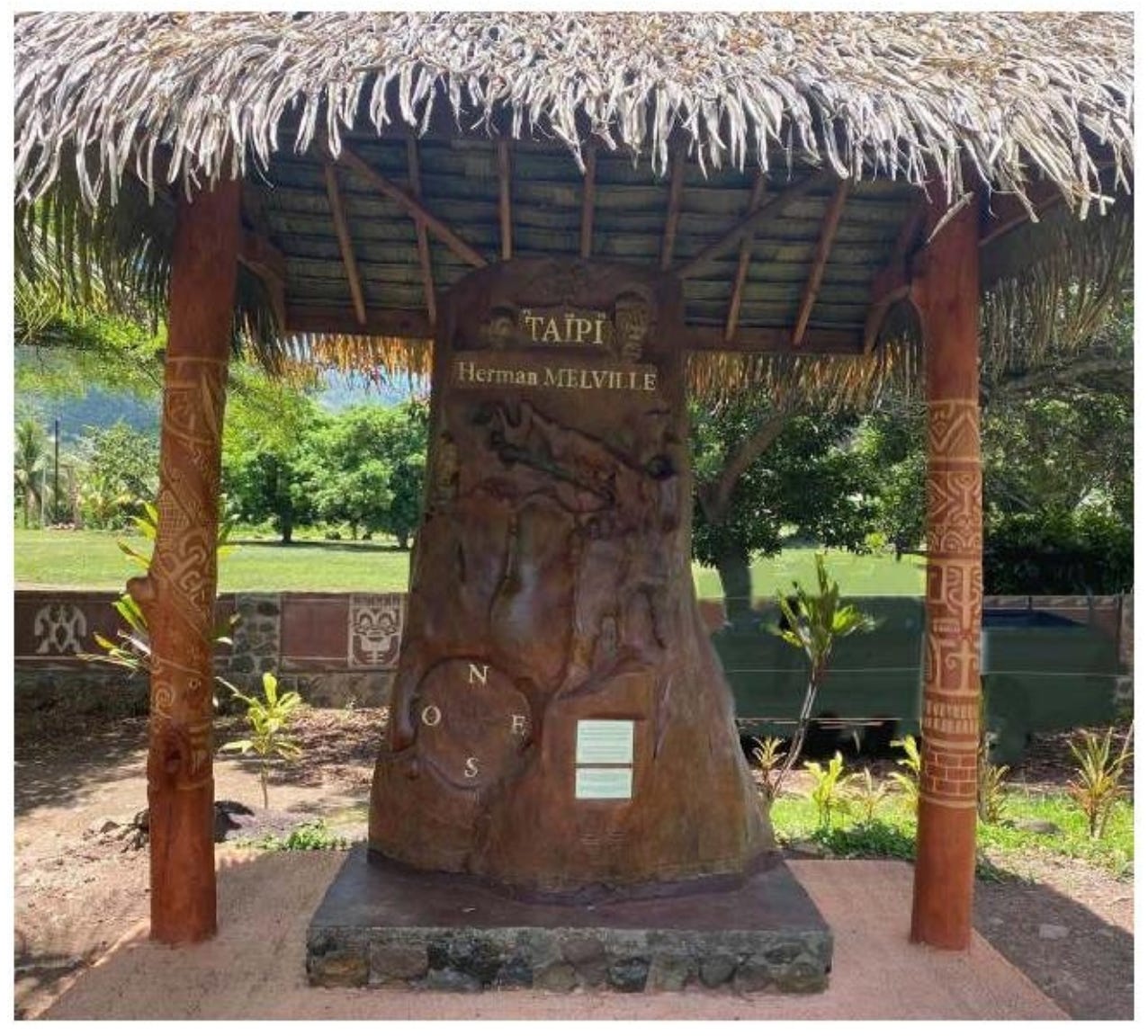

Even worse, the bust was literally the only sculpture of his likeness anywhere in the world. (This excludes the amorphous monument that stands on Nuku Hiva sculpted to honor his brief stay on the island in 1842).

This oversight, it was recently announced, is soon to be rectified by New Bedford, again leading the charge of remembering Melville. Earlier this month the city unveiled its selection for the design of an 8-foot-tall statue of Melville standing in a swell of whale ribs, to be installed beside the Seaman’s Bethel in 2026.

To be sure, I’ll be eager to see it when it’s completed, but in the meantime, it was time to give New York a little nudge and find Herman’s Head.

Chapter 1: 6 Pearl Street

First, let’s take a stroll through the history of the odd elbow of a corner in Lower Manhattan where Melville was born on August 1, 1819 — and, to be clear, he was indeed born at home at 6 Pearl Street.

The house sat practically at the southwestern edge of the island just steps away from the Battery. I marked the approximate location of the house with a red dot on this map from 1867, near the curving intersection with State Street.

The Melvill family (still without the final -e) had only lived in the house for a few months when Herman was born, having spotted it on the market the previous summer. Herman’s mother Maria wrote to her brother on September 12, 1818 describing a few promising options for their new house in the city. The one at 6 Pearl Street, she had decided, would be a most “Healthy situation" for the family.

“… the other is a New house next to Langs which you spoke of with a Basement, kitchen on the first floor, handsome Parlour, large Pantry in the Hall & a neat Pantry in the kitchen, & Deep in, fix'd in the Wall; first floor, two Elegant rooms connected by huge folding doors large Pantry between Black Italian Marble mantlepeices & between the folding doors a place for a Lamp.”

Somewhat incredibly, I came across this drawing from 1858 of the Melvill’s exact corner as seen from State St. I marked what one city historian and archaeologist believes to be their house, the middle of the three squat two-story houses a few buildings back.

The family, including children Gansevoort and Helen Maria, moved in on May 12, 1819. It can be hard to imagine now, but the neighborhood was then part of a still small-town community; Herman’s father Allan thought to be among “the most airy situations in New York.” Though it was on the precipice of becoming the center of the nation’s commerce after the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, the Melvills would have lived modestly without a sewage system and water from a backyard well.

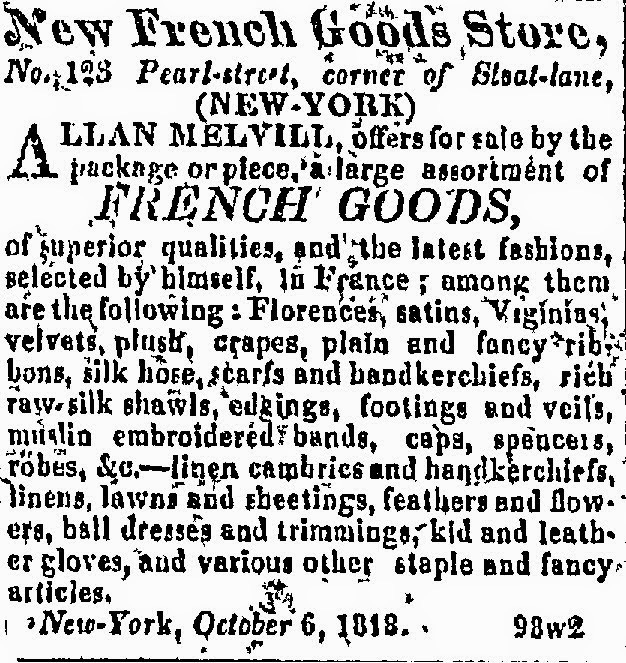

Allan had already established himself in the neighborhood, setting up a store just a few blocks away at 123 Pearl Street where he sold a “large assortment of French goods” including satins, fancy ribbons, leather gloves, and silk shawls.

About three months after moving in — and 10 days past due — Herman was born at home at about 11:30 p.m., delivered by Dr. Wright Post. (Interestingly, the family had a visitor that evening: Herman’s uncle Captain John D’Wolf, who makes an appearance in Chapter 45 of Moby-Dick.)

Allan wrote to his brother-in-law the next day:

With a grateful heart I hasten to inform you of the birth of another Nephew, which joyous event occurred at 1/2 past 11 last night — our dear Maria displayed her accustomed fortitude in the hour of peril, & is as well as circumstances & the intense heat will admit — while the little Stranger has good lungs, sleeps well & feeds kindly, he is in truth a chopping Boy.

All that said, the Melvills lived at 6 Pearl St. for just a year, and baby Herman was only there about half that time. In September 1819, Maria took her three children on the overnight ferry to Albany to escape the city’s ongoing cholera epidemic, staying there two months. She and the children went back to Albany the following June, this time to avoid the yellow fever epidemic. When she returned in September 1820, she found that her husband had moved the family’s residence a few blocks north to 55 Cortlandt Way.

So ends Herman’s physical connection to the spot, but we celebrate the location regardless for its significance to shaping his life’s story and his work. Fans of Moby-Dick need only a quick glance at a map of Lower Manhattan to spot many familiar names from Chapter 1, including the Battery, Coenties Slip, Corlears Hook, and Whitehall Street are all within a stone’s throw of 6 Pearl St.

The year of his birth also has added significance for prompting Raymond Weaver’s centenary essay on Melville in The Nation in 1919 which in turn led to the Melville Revival in the decades to come.

Chapter 2: The Petroleum Man

After the Melvill family departed in 1820, 6 Pearl Street would be occupied by a dozen of more families over the remainder of the 19th century as big changes came to the neighborhood. In 1824, the city leased the the lightly-used Fort Clinton at the west end of the Battery, practically at the front door of the former Melvill residence. The city turned the fort into Castle Garden entertainment venue sporting a beer garden, exhibition hall, and a 6,000-seat theater hosting such acts as Swedish opera singer Jenny Lind and Lola Montez, famous for her “tarantula dance.”

Castle Garden, however, will be more familiar to anyone with an interest in genealogical research for serving as the country’s first immigration depot from 1855 to 1890 until the construction of the facilities on Ellis Island. More than 8 million immigrants were processed through Castle Garden in this period, including millions of Irish refugees of the the Great Famine, and many of the names appearing in city directories as having lived at 6 Pearl Street in the mid-1800s reflect this history: Michael Connor, James Houlihan, John Dunphy, James Fitzsimmons, and so on.

The stately row houses on the first block of Pearl St. remained as they appear in the lithograph above until the 1890s, when they were purchased piecemeal by Robert A. Chesebrough, a man who had recently come into a great fortune. Rather uncannily, Chesebrough began his career as a chemist “distilling kerosene from the oil of sperm whales.” (Even wilder, Chesebrough’s earliest American ancestor arrived in the new world in 1630 and settled in Pequot, Connecticut — present day Stonington.)

But it was while working on oil rigs in Pennsylvania that Chesebrough struck gold, so to speak, when he discovered petroleum jelly — or rather realized the potential for this naturally occurring byproduct from the production of petroleum oil. He sold it under the brand name Vaseline “for medicinal, pharmaceutical, and toilet purposes.”

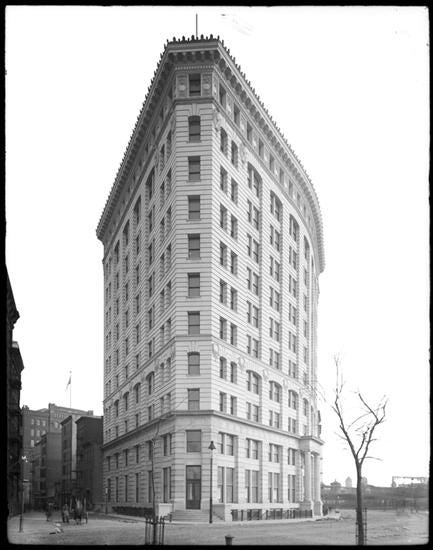

Vaseline made Chesebrough tremendously wealthy, and after purchasing all of the buildings on the corner of Pearl and State Streets he erected an 11-story building as the headquarters for his manufacturing company. The building, which stood until the 1960s, was given the address 17 State Street, seen here circa 1900 from about the same vantage point as the lithograph above.

Despite his start in a whaling-adjacent industry, neither Chesebrough nor the successive tenants of his building seem to have offered any recognition of Melville as a former inhabitant of the space. Nor is this surprising; Melville, of course, was largely forgotten outside of a small (if ardent) cadre of fans until the 1920s. His earliest address might not have come to light — that is to say, possibly no one cared — until the first full-length biography published by Raymond Weaver in 1921 which begins at that very corner:

The High Gods, in a playful and prodigal mood, gave to Melville, to Julia Ward Howe, to Lowell, to Kingsley, to Ruskin, to Whitman, and to Queen Victoria, the same birth year. On August 1, 1819, Herman Melville was born at No. 6 Pearl Street, New York City.

Yet even through the height of the Melville Revival, no one seemed to care very much about the site formerly known 6 Pearl St. It wasn’t until September 1957 that the members of the still-nascent Melville Society considered a suggestion from artist Gil Wilson to “take some action to secure a plaque to be placed near the site of Melville’s birthplace.”

Wilson, once an assistant to Rockwell Kent, had spent the previous decade obsessing over Moby-Dick and producing more than 200 drawings and paintings inspired by the book, recently collected and published by Hat & Beard Press. (You may also recall from a recent post here that it was Wilson who inspired Gregory Peck’s “Amish” beard, forever altering the public’s conception of Ahab).

The Melville Society’s annual members approved the idea and appointed a committee “with power to take appropriate action in the name of the Society with regard to the plaque.” However, so far as the organization’s quarterly newsletters reveal, it seems that momentum for the plaque petered out, and the idea was shelved for the time being.

Chapter 3: The Seamen’s Inn

Recognition for Melville finally came in the 1960s, when another all-too-apt organization was looking for a spot to construct its new flagship building: the Seamen’s Church Institute. Founded in 1834 and still in existence today, SCI provides “relief and support for mariners” through training, professional development, government and legal advocacy, and religious services through its affiliation with the Episcopal Church.

SCI headquarters had previously been located just a few blocks away on the edge of the water at 25 South Street, famous for its 60-foot-tall Titanic Memorial Lighthouse perched on the roof and visible from up to 10 miles away. For nearly fifty years, a “time ball” at the top of the lighthouse would drop down at twelve noon so that ship captains in the harbor could set their watches. There were also dormitories and rooms to accommodate up to 580 seamen when their ships were docked in the area, some of whom became permanent residents after their retirement from life at sea.

With the changes to the shipping industry by the mid-1960s, SCI came to find that they had too much lodging for the number of interested seamen and not enough space for more pressing uses. So, in 1966 the organization purchased the Chesbrough Building and a few additional parcels and built its own 23-story tower.

The building, which took the address 15 State Street, provided a safe harbor for visiting mariners, including a chapel, cafeteria, bag storage, kitchens, a library, and even a post office that served as the only permanent mailing address for many of its visitors. The top 18 floors offered enough rooms to accommodate 340 seamen, about half as many its previous building.

SCI recognized from the start the hallowed ground on which it was built, erecting a plaque in honor of Herman Melville as soon as the building opened in 1968. Paid for by the New York Community Trust, the plaque was affixed to the Pearl St. side of the building and recognized the author’s connection to the spot and contributions to American literature.

The organization also paid homage to Melville from with occasional articles about his work in its monthly newsletter, The Lookout, and in July 1969 marked the 150th anniversary of Melville’s birth by devoting nearly the entire issue to his biography and what life was like in the Financial District in the early 19th century.

Unfortunately, SCI appears to have again misread the tea leaves of the shipping industry and the need for 18 floors worth of subsidized lodging, and by 1985 had to move on once more. A spokesman told the New York Times that the building had become a “financial drain.”

Seamen paid a small amount to stay in the rooms but the institute always ran at a deficit, according to Carlyle Windley, a spokesman. The building was erected just at the time the shipping industry was going through a profound change to containerization that sharply reduced the number of men needed on vessels sailing in and out of the port.

''Instead of being an asset, the building was becoming a financial drain,'' Mr. Windley said. Another negative factor was the cost of operating the building, which had been constructed before the oil crisis of 1973 and lacked sufficient insulation.

The organization was “almost as nomadic in recent decades as the seafarers it serves,” wrote the Times.

When the building was torn down in 1986, so too went the Melville plaque.

Chapter4: Peddling Heads

Finally, we arrive at the present. Or at least the near-present.

When the SCI building was demolished it was quickly replaced with the 42-story skyscraper that still stands there today facing New York Harbor. Like both the Chesebrough Building and SCI headquarters before it, it’s slightly rounded in order to fit the wedge-shaped lot as established by Dutch settlers 300 years earlier.

17 State St., as it’s known once again, was completed in 1988 for developer William Kaufman at a cost of “well over $100 million.” When it was finished, its distinctive facade of reflective glass became a prominent feature of the city’s skyline as seen from south. The New York Times bit on its nautical history, calling it a “high-tech version of a lighthouse, standing almost at the edge of the sea.”

The footprint of each successive building overtaking 6 Pearl St. has grown larger and larger, such that the actual site of Melville’s house would now be located where you see the number 9 in the image below.

Kaufman only owned the building for a few years, defiantly maintaining high rent prices and finding few buyers. “After three years of leasing that verged on the comatose” per the Times, it was sold in January 1990 to the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of Manhattan — just the sort of organization you might expect to be amenable to the idea of honoring Melville at their brand new headquarters.

The Melville community clearly recognized the opportunity to replace the plaque. In March 1990, Melville Society Chair Thomas Heffernan sent a letter to the mayor’s director of special projects asking for help. The letter, which I received as part of a request from the NYC Municipal Archives, was more generally in regards to their efforts to establish a “Melville Week” to recognize the 100th anniversary of his death in 1991. But while they had the director’s attention, Heffernan asked if they could also speak to the new owners of 17 State Street on their behalf to see if they would be open to the “erection of a statue or comparable memorial to Herman Melville.”

It seems natural to address your office about our plans. We would appreciate it greatly if the mayor could proclaim the week of September 22 to 28 “Melville Week.” […]

One way in which the city’s help might prove timely is in intercession with the management of a lower Manhattan office building where we plan to ask for the erection of a statue or comparable memorial to Herman Melville—the site is the site on Pearl Street where Melville was born. We have not yet approached the management of the building with the idea.

The reply from the mayor’s office was unfortunately not archived along with the rest of the material about Melville Week, which was indeed proclaimed by Mayor David Dinkins in late September 1991. Events included seminars, exhibitions of Moby-Dick art and source material, and staged productions of Bartleby the Scrivener starring Fritz Weaver held (of course) at the Seamen’s Church Institute’s new headquarters at 241 Water Street.

As for the statue and the intercession with the owners of 17 State Street, we can only infer that Heffernan was told he’d have to wait. It would be another five years before Herman’s Head began staring out from the plaza wall.

To be continued…

In an upcoming post, I’ll dig into the origins of the Melville bust that once graced the 17 State St. plaza, try to figure out why it suddenly disappeared, and see what we — yes, we — can do to get it spruced up and restored to its rightful place yet again.

Stay tuned!

Excellent post, thank you. The Melville history in lower Manhattan has been of great interest to me lately, especially after reading the novel “Spadework for a Palace” by Krasznahorkai, where the author is obsessed with tracing Melville’s footsteps from the years he lived on East 26th and worked at the customs house

Great post! As a resident NYC'er, I'd love to see more Melville acknowledgement. This isn't the first historical plaque I've heard of disappearing – it seems to be a common fate for history in such a fast-moving city, unfortunately.