Venerable, Moss-Bearded Ahab

; or, did Gregory Peck permanently change our conception of Ahab?

How you imagine the characters of Moby-Dick might depend on which illustrated edition of the book you first read, which film or tv adaptation you’ve watched most, or maybe which details from the book stuck with you most vividly. When you think of Starbuck, for example, is he tall, lean, and with skin as “hard as twice-baked biscuit,” as Melville intended? Or is he more of an average height (and British) like Leo Genn in the 1956 film adaptation, pale like Ethan Hawke, or somewhat Lurch-like in Rockwell Kent’s illustration?

What about Ahab? He’s described as being “grey-headed” with a white scar running from head to toe, and wears a “slouched” hat as if to hide from god — qualities which, aside from the missing leg, diverge somewhat among depictions.

But what I’m interested in today (unintentionally apt for “No Shave November”) is an often-overlooked detail about his character that has varied the most in the 100+ years of depicting Ahab: his beard. The fact that he’s even said to have a beard might come as a surprise as it’s curiously unmentioned until the last few chapters, finally appearing in Chapter 130: The Hat and compared to the gnarled roots of a dead tree:

He ate in the same open air; that is, his two only meals,—breakfast and dinner: supper he never touched; nor reaped his beard; which darkly grew all gnarled, as unearthed roots of trees blown over, which still grow idly on at naked base, though perished in the upper verdure.

The imagery invites the sense that Ahab’s mind has suffered a similar kind of death to that tree, exhibiting life only at the more ‘base’ parts of his soul. We might wonder, then, why his beard seems to freely come and go among depictions in illustrations and visual adaptations, and whether there’s any kind of trend we can comb out.

Ahab’s Beard

I first saw a question about Ahab’s beard on Reddit a few years ago, where someone asked why Ahab was “nearly always portrayed with a chin beard.” Now, technically, the beard we often see Ahab sporting is called a “Shenandoah,” also known as an Amish beard, a chin curtain, a Lincoln, a spade beard, or — interestingly — a “whaler.” Regardless, flipping through my mental rolodex of Ahabs, the premise of the question didn’t exactly ring true.

At the time I did a quick image search for “Captain Ahab” to see what came up. Ahab was most famously portrayed by Gregory Peck in 1956, but also by Patrick Stewart in 1998, and by William Hurt in 2011. As you can saw in the side-by-side comparison of the actors above, Peck does have that thick, manicured chin beard the question probably had in mind. Stewart, meanwhile, is clean shaven, while Hurt has a full, scraggly beard.

Otherwise, the initial image search results were surprisingly hairless. The first image was from I.W. Taber's illustration from 1902, in which he doesn’t have a beard. Then there was the clean-shaven Denis Levant in the 2007 French film Capitaine Achab; Mead Schaeffer’s beardless Ahab from the 1920s; the beardless John Barrymore from the 1926 silent adaptation and 1930 remake (though he sports a slick mustache); and Rockwell Kent’s illustration of yet another beardless Ahab.

At the time, this felt like enough to answer the question in that the beards and no-beards were actually about even. As I later found with depictions of which leg he was missing, by sheer coincidence it just seemed to average to about 50/50. But now that I happened to have a collection of 100 depictions of Ahab, it felt like time for a more thorough study.

“Speak, thou vast and venerable head!”

I should note again, that this is not exactly scientific. I arbitrarily chose a goal of 100 Ahabs with as much variation in the mediums as possible. That said, I found an example from virtually every illustrated version of the book published in the 20th century and many from the 21st; every film/TV adaptation I’m aware of, plus many cartoons, stage adaptations, and significant artistic interpretations mentioned in places like Elizabeth Schultz’ study Moby-Dick: Moby-Dick and Twentieth-century American Art from 1995. So, it’s not nothin’.

All that said, I found that of the 100 Ahabs in total, 49 had a beard and 35 did not. Another 16 were indeterminate — either he wasn’t shown from the front, the image was too small or lacking detail to determine, or was too abstract. For our purposes, I’ll remove those 16 from the counts, so we’re left with 84 Ahabs. But when I laid it all out in a spreadsheet, something more interesting showed up.

First, here are some clean-shaven Ahabs, all taken from the 1920s to the 1940s.

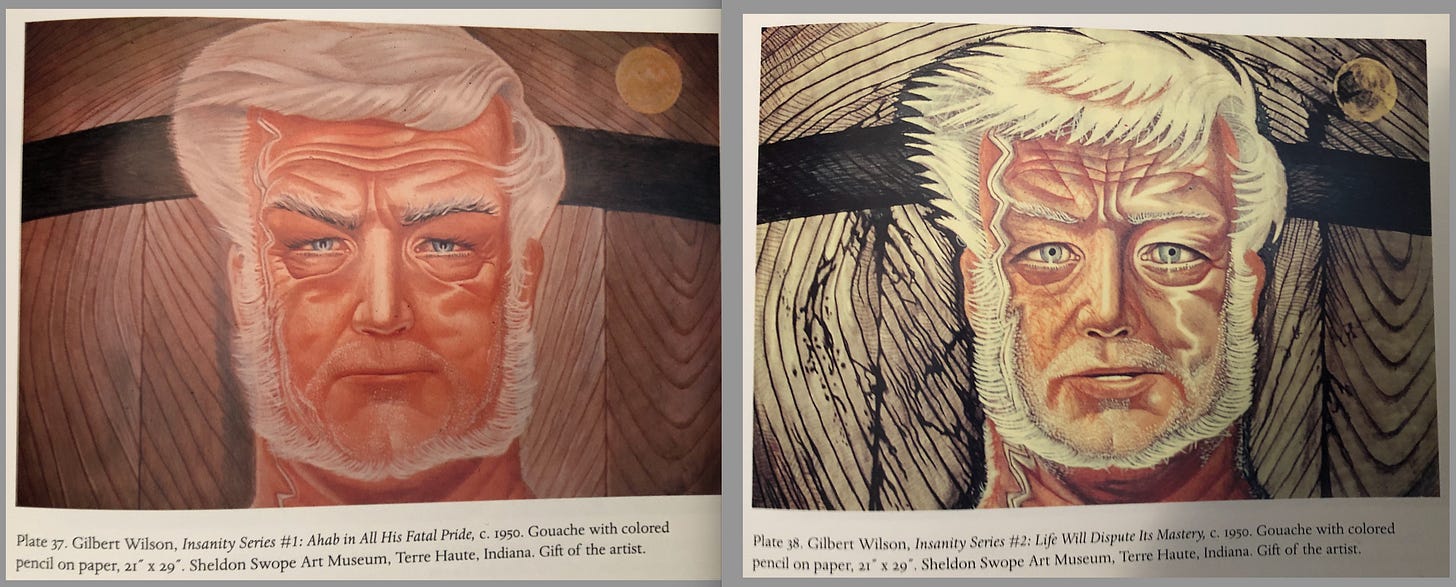

What’s interesting is that in the 19 depictions of Ahab from 1899 to 1955 (i.e., prior to the release of the John Huston film starring Gregory Peck), just four of them showed Ahab with a beard. And of these four, only the Ahabs in Gilbert Wilson’s series of paintings approached what you might call a Shenandoah or “chin beard.” (Although, as you can see below, Ahab in fact has a faint mustache).

However, after 1956 — excluding Peck’s depiction itself — 45 of the 65 depictions (70 percent!) had a beard. Even more remarkable is that 33 had a chin beard like Peck’s, compared to the 10 who had a full beard. One had more of a goatee situation, while a few others had 'mutton chops’ which I didn’t count as a beard.

In other words, prior to Gregory Peck, 1 in 19 Ahabs had a chin beard — and just barely. After Peck, it was 33 out of 65. Pretty wild!

How Greg Got Grizzled

While this was an interesting enough finding, I wanted to know more about how that beard ended up on Peck’s face in the first place. Who can we credit for permanently altering our idea of Ahab?

First, I should say for the record, Peck’s beard was his own. This was no paste-on job. Lynn Haney, author of Gregory Peck: A Charmed Life, wrote that Peck was cast he “dove into the project with gusto,” impressed by Huston’s commitment to staying true to Melville’s vision. “Ahab is the best part I’ve ever had,” he remarked, “and all the qualities of the book have been retained in the script.” Peck let all of his hair grow out in anticipation of filming, commenting: “I’m getting grizzled by the minute.” Here he is in December 1954 in Madrid, Spain on a vacation from shooting but still sporting some anachronistic facial hair.

To find out more, I flipped through nearly a dozen biographies and autobiographies of director John Huston, screenwriter Ray Bradbury (including Bradbury’s loosely fictionalized account of working on the film, Green Shadows, White Whale), and cinematographer Oswald Morris’ autobiography titled Huston, We Have a Problem. While I learned some interesting history about the film’s production — e.g., the tyrannical Huston tormenting Ray Bradbury and his wife, the multiple instances where Peck was almost killed re-enacting the final battle, etc. — there was little account of the beard.

The closest thing to a lead came from a biography of Peck by Gary Fishgall, which noted he “worked with the Warners makeup department to devise a look for the character, which involved growing his hair long and adding a Lincoln-like beard—with touches of white in both—plus a scar along his cheek.” But this is about what I had figured out from IMDb; the make-up department for the film was led by Charles E. Parker, joined only by chief hairdresser Hilda Fox. Parker may not be a household name, though some of his other credits include Lawrence of Arabia, Murder on the Orient Express, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Star Wars: A New Hope. He died rather young in 1977.

So while I couldn’t find out much else about Charles E. Parker, I was ready to credit him with ultimately creating the look so often associated with Ahab today… until something else clicked. When I was looking for images of Gilbert Wilson’s Ahabs to use above, I landed on the website of Hat & Beard Press, which published an edition of Moby-Dick a few years back using Wilson’s paintings as illustrations. (The publisher, despite the strange coincidence, was named for the Eric Dolphy song, not Ahab’s facial hair and accessory). The site notes that Moby-Dick was Wilson’s lifetime obsession, “for which he produced more than 200 paintings and drawings, and helped inspire Huston’s 1956 film adaptation starring Gregory Peck.”

I didn’t think too much of the claim until I was browsing the collections of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Archives for any last clues in their extensive holdings in the John Huston collection. Although the actual items in the collection aren’t digitized, item descriptions contained some intriguing details. For example, in one letter, Huston is said to thank an MGM executive for allowing Parker to do makeup for them film. In other words, Parker wasn’t a Warner Brothers guy but ‘on loan’ between studios. But there were also several items in the Huston collection related to Wilson, including a synopsis and libretto of Wilson’s failed attempt to produce a musical/opera titled “The White Whale,” and correspondence from Wilson about the film’s production.

I suddenly recalled that I had a biography of Wilson by Edward K. Spann, which started putting all the pieces together in terms of how this strange artist, obsessed with the idea of what he called a “fat Ahab,” ever got connected to Hollywood legends like Huston and Peck in the first place. It seems it all started with Huston’s father, actor Walter Huston, who Wilson wanted to cast as Ahab in his grand production.

Even before hopes of making The White Whale as an opera began to fade, Wilson was thinking of presenting it as a movie, particularly as a musical drama on film… He considered using the movie actor, Walter Huston, as Ahab, an idea which soon brought him into contact with Huston’s son, John, the movie producer. […]

Beginning in 1947, as he tried to work out the visual elements of The White Whale, he began producing a series of drawings and paintings presenting his ideas regarding the characters and scenes of Moby Dick… It was Ahab, however, who appeared in roughly half of the paintings, so many that Wilson wondered whether the public might catch on to his love for fat men. In one picture, he depicted a “wild-hearted” Ahab and got excited: “I strain the damn muscles of my neck with the fury of my feelings trying to be Ahab as I draw.”

Wilson created so many paintings that in 1947 he decided to display 100 of them at the Newton Art Gallery in New York, in part sponsored by Walter Huston who had become a supporter. The exhibit had the intended effect on John, who took on Wilson’s idea as his own, working out how to produce a film with his father as Ahab. Wilson was elated and fully expected to become a consultant to the film, ramping up his painting and working on design elements in anticipation.

By the time it went into production in 1954 after several years of delays, he found he’d been entirely sidelined. It was a classic Hollywood story, but he seethed about "the way I have been left out of the whole thing to the point of reducing my work to an absolute zero creatively." Spann adds in his Wilson biography that he specifically hated the idea of the Lincoln-esque Gregory Peck being cast as Ahab. (Walter Huston had died in 1950 at the age of 66).

Still, Wilson had reason to expect that he would be at least consulted, since he had spent years devising ways of turning Moby Dick into a dynamic visual presentation… When he learned that Gregory Peck had been signed to play Ahab, he wrote to Huston gently criticizing Peck for not looking like his version of Ahab--more privately, he complained that the actor looked more like Abraham Lincoln than the heavy-set tyrant that he imagined Ahab to be. He suggested that his own paintings might be used to help Huston better visualize the film.

It’s not clear whether Huston ever took Wilson’s advice and used his paintings for design elements, but considering that his Ahab was the first and only chin beard I found prior to 1956, it’s hard not to consider it a strong possibility. And in fact, there’s another clue that Huston was listening to Wilson however much he denied him being part of the film.

In August 1952, while still waiting for the film to go into production, Wilson published an unusual article titled “Moby Dick and the Atom” in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists journal, an unlikely place for such an artist to be opining about recent frightening advances in physics. In the article, Wilson discusses similarities between the white whale and the atomic bomb, and connects the power within the atom to the fuel derived from the whaling industry. Wilson then takes the analogy one step farther, suggesting that the location of the final battle with the whale was perhaps near Bikini Atoll, the island chain being used as a nuclear test site.

Only a century after Herman Melville wrote his great book, our own American atomic engineers unwittingly selected almost the very spot in the broad Pacific some few thousand miles southeast off the coast of Japan where the fictional Pequod was rammed and sunk by the White Whale. The ubiquitous mythic monster breaches again today at Bikini. […]

I do not know how true it is that atomic radiation can result in sterility, but if there is any basis for it, then Moby Dick and the atom are still further uniquely analogous.

As far as I can tell, there was no one but Wilson suggesting Bikini as the site of the final battle with Moby Dick — at the time or since. The location also isn’t named anywhere in the book. So then what are we to make of this line in the 1956 film, when Ahab meets Captain Boomer and confirms that they’re headed in the right direction?

AHAB: Where did you last see the white whale?

BOOMER: Off the Cape of Good Hope. He was heading northeast towards Madagascar.

AHAB: Starbuck! Starbuck! Do you hear? A white whale last month off Good Hope. My chart is right and true! He'll be off Bikini when the April moon is new.

It’s only conjecture, but Wilson may have been not just the first artist to give Ahab a chin beard, but in fact might directly responsible for influencing Gregory Peck’s Ahab, and dozens of Ahabs to come.

Weird Beard Premiered, Jeered

Regardless of where the beard came from and its legacy, it was decidedly not a hit among critics in 1956, who — like Wilson — chuckled at Peck’s uncanny resemblance to Abraham Lincoln. It didn’t help that they were generally not impressed with his performance, either. The response was so universal that Peck’s biographer Gary Fishgall had to wonder why no one on set thought to hand him a razor:

As for his performance, most of the critics agreed with Wanda Hale of the New York Daily News, who found him “stiff and stagey.” In fairness, he had a number of strikes against him. To begin with, his costume and makeup immediately evoked the image of Abraham Lincoln, a fact noted in virtually every review. Why no one on the production team attempted to redress this distraction is a mystery.

One biography of Huston disclosed that Warner Bros executives panicked when they saw previews and wanted to shelve the movie — or at least cut it down to just action sequences and maybe insert a love interest. Huston ultimately won the editing battle, but a compromise was reached: the movie poster was ordered to be changed, painting out Ahab’s beard.

Critics, though, were unrelenting in their ridicule of Peck’s look. Time Magazine wrote that Peck had “an unlucky resemblance to a peg-legged Abe Lincoln.” The New York Times said that Peck "gives Ahab a towering, gaunt appearance that is markedly Lincolnesque.” Variety complained about the distracting white scar and patch in Peck’s beard, “leaving aside the fact that the star not infrequently suggests a melancholy Abe Lincoln.” One nationally-syndicated film columnist put it more bluntly: “This is how Abe Lincoln would have looked if he’d been shot in the leg instead of the head.”

Over time, critics seem to have lightened up about Peck’s look perhaps for the obvious reason: Peck’s chinbearded Ahab became so ubiquitous in the decades to follow that it’s become part of the character. It belongs just as much to Ahab as it does to Abe.

The Whaler

I’ll finish with one last question: is it even likely that Ahab would have had a chin beard as a 19th-century, Quaker whaling captain? After all, Bildad is described as having “no superfluous beard, his chin having a soft, economical nap to it, like the worn nap of his broad-brimmed hat.” Many early, notable Quakers were also clean-shaven, and a quick search for portraits of 19th century whaling captains suggests that they too had no beard or just a mustache.

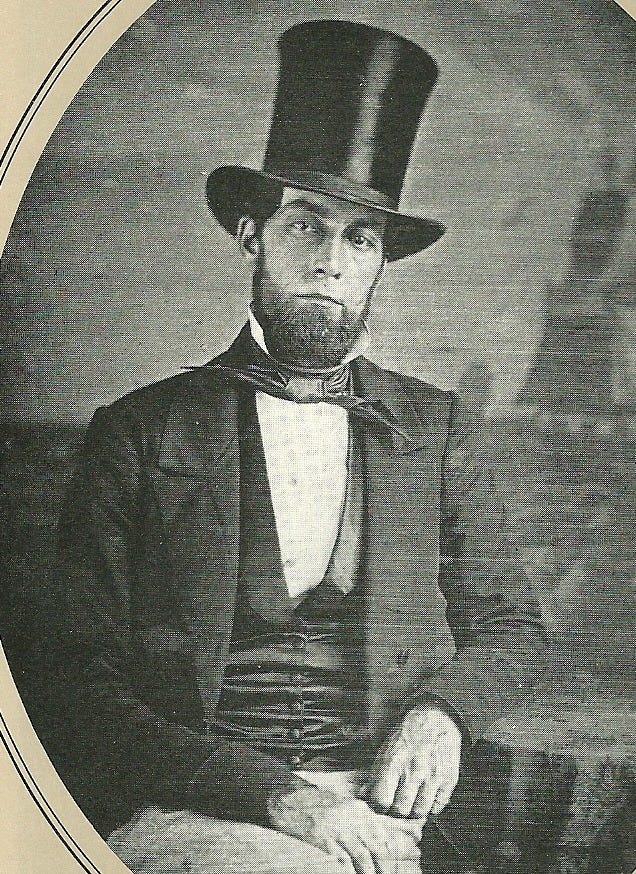

But I also found several historical images that could serve as a mental model of Ahab. For example, here’s Captain Edward S. Davoll, captain of several whaling voyages from 1846 to 1862, including the bark Cornelia sailing from New Bedford.

Captain George White (1819-1893), who spent 26 years rising through the whaling ranks from cabin boy to captain, might also fit the bill. In character, though, he might have been a bit more Stubb-ish, quoted as saying "I can't understand why any man should be afraid of a maddened whale in mid ocean or to launch a life boat through raging surf."

All that said, let’s return to that lone quote from Moby-Dick about Ahab’s beard, which as I noted comes toward the end of the book. Ahab, we’re told, has reached a point of madness wherein he never leaves the deck — not even to sleep. He “went no more beneath the planks; whatever he wanted from the cabin that thing he sent for.” It’s in this moment when we first learn that he only ate two meals and stopped shaving his beard, obsessed with finding Moby Dick.

In other words, the image I get from this passage isn’t Gregory Peck’s chin beard or even the more wild one worn by Willian Hurt in the 2011 miniseries. In fact, it’s one I’m not sure I’ve seen in any depiction yet. Whenever someone hires me as a production consultant for the next adaptation of Moby-Dick (please and thank you), I would advise that Ahab’s facial hair mirror his final descent into madness, clean-shaven to start and maintaining his appearance throughout the middle third of the story. For all his madness, Ahab is still sensible enough to allow the crew to hunt other whales and find ways to appeal to their ‘lower layers’ as he leads them toward their ultimate destruction. It’s only after a certain breaking point that his beard goes ‘unreaped’ (symbolized also by his hat being taken by a wild bird in the same chapter), signifying that he’s beyond all hope or reason.

I do like your idea That the beard is a measure of Ahab’s madness